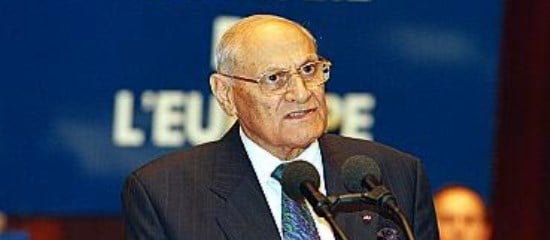

Censu

Tabone

President of Malta

Speech made to the Assembly

Thursday, 1 July 1993

It is with pleasure, tinged with emotion, that I address this august Assembly, of which I have been a member for a number of years. I can see before me many familiar faces — people who, over the years, have been the protagonists of notable debates and resolutions and with whom I have entered into lively debate, although in the spirit of friendship and mutual respect that characterises debates in the Assembly, and to which you, Mr President, can bear witness.

This Council, established at the end of the last war in troubled and unsettled times, remains the oldest and largest representative forum in Europe. It has not been a static or fossilised institution but has grown and has developed with the changing times, maintaining its identity as a laboratory of ideas, methods and standards, for those countries that were prepared to accept its type of parliamentary democracy, respect for the rule of law and the preservation and promotion of human rights. It is of comfort to us all to recall the vital debates held in this Assembly as a preparation and as a prelude to decisions in other European organisations.

While lacking the executive functions and economic possibilities of the European Parliament, this Council maintains its moral authority and its preoccupations with social, cultural and legal matters, and in particular with human rights. The fact that its members have invariably been members of their national parliaments has added weight to its deliberations. Committed to such values, the Council of Europe has contributed for more than forty years to the shaping and development of a European family of nations.

Malta became a member of the Council of Europe in April 1965, soon after achieving independence, and has since participated actively in the orchestra of the Council of Europe member states, at parliamentary, ministerial and intergovernmental levels, sharing the preoccupations inherent in the process of building a truly democratic and pluralistic Europe.

Over the years, Malta has made use of the instruments offered by the Council of Europe and has also offered its services in connection with issues related to the Mediterranean basin and to the rest of Europe. After achieving independence, Malta sought to reorganise its economy, which had previously depended in large measure on the defence spending that accompanied its former colonial status – taking advantage of its geographical position, its history and past experiences. We have established and developed new industries, including tourism, and favoured investment from abroad, while consolidating our political independence and sovereignty. We have played our part in this Council’s efforts to shape European history in the light of European civilisation, heritage and culture. The building of a new and modem Europe remains a primary task, as does the search for greater unity among our member states. The Council remains, I believe, an organisation that is influencing the growth of Europe on the basis of humanistic principles.

We should never forget that the Council of Europe has been a solid platform for peaceful and constructive dialogue amongst all the nations of western Europe, providing perhaps a unique forum in which to establish dialogue between countries that had been at war with each other for many centuries. This expertise in co-operation is an asset in the process of consolidating democratic reforms.

The Council of Europe’s first meeting of heads of state and government, scheduled to take place in Vienna from 8-9 October 1993, is therefore most timely. It offers a unique opportunity to adapt our Organisation to the challenges of a new Europe. We look forward to the decisions that the summit will take on current issues of great importance.

The Council of Europe’s role as the organisation for political co-operation, in which all European states have or will have the possibility to participate on an equal basis, should be encouraged. It is clear to all of us that our continent is going through a very dramatic stage, and the summit will no doubt also wish to take a stand on the future and structure of the former Yugoslavia and so help to bring peace to that troubled land. The recommendation that your Assembly adopted yesterday in connection with that summit rightly emphasises the importance of a decision to add a protocol on the rights of minorities to the European Convention on Human Rights. That would demonstrate that lessons are being drawn from the tragedy in the former Yugoslavia and might well prove to be an effective way of preventing similar conflicts in the future. At the same time, the Council of Europe should not neglect its traditional role in protecting human rights, even if it is necessary to reform the mechanism of the European Convention on Human Rights. Here, too, the Assembly has made clear proposals, which have already been accepted by most member states. I trust that those that are still reluctant may in time reconsider their positions.

It is clear from the above that, with increased membership and with the formidable tasks ahead, the structure of the Council of Europe needs to be strengthened. I believe the resultant cost-benefit ratio would amply justify the additional expenditure.

May I now turn to a specific aspect of the Council of Europe’s work in which, as some of you will well remember, I have been particularly involved and to which I still attach great importance – lam referring to bioethics. Bioethics is a field that is at the frontier between good and evil, in which scientific aspirations often clash with collective interests and moral codes. Scientists should repeatedly be reminded that not all that is feasible is permissible. The Council of Europe – and, in particular, this Parliamentary Assembly – has been at the forefront of reflection and of codification proposals since the early 1970s in many specific areas such as genetic manipulation and organ transplants and the use of embryos for research and for commercial purposes.

The development of research and its application to this field – whose speed more than tripled in the late 1980s, with tremendous commercial interests at stake – led to efforts to produce a more comprehensive and binding document. Momentum has been gathering for the elaboration of European legal instruments. I recall with humility my declaration before the Assembly in 1988, as Minister of Foreign Affairs and President of the Committee of Ministers; the efforts of the Secretary General and, last but not least, the political push made by the Parliamentary Assembly.

I am informed that, as a result of those efforts, a specialised committee has now made considerable headway with the drafting of a convention. The two protocols, on medical research and organ transplants, are nearly ready, and the main part – which deals with general principles – is shaping up. However, problems remain: there is still some reticence and divergence on fundamental issues. I trust that it will none the less be possible to open the text to signature before the end of the year.

It is vital that a document of such importance is adopted only after democratic control, such as the expression of parliamentary opinion in our respective countries; that it does not simply represent a common denominator, containing only platitudes, but is of sufficient substance to be likely to be considered as a solid reference for some time to come, as was the case with the European Convention on Human Rights; that it is continually brought up to date in later years; and, finally, that it is also open to non-member countries, bearing in mind that too limited a geographic scope might lead to the creation of “bioethics havens”.

Laying down ethical premises and acceptable standards in bioethics – not autocratic restrictions, as some may suggest – is a test case for Europe, and for the Council of Europe in particular. The Council of Europe should be congratulated on playing a leadership role courageously. It should be encouraged to continue with new initiatives, such as offering a platform to European ethics committees.

I also wish to refer to the co-operation of the countries of Europe with those on the southern shore of the Mediterranean. I am fully aware that, here again, the Council of Europe has spared no effort over the years to establish dialogue with the countries concerned, but I believe that further efforts in that direction would be opportune.

We are constantly reminded that many European countries which have traditionally been “emigration” countries have become “immigration” countries, owing to the enormous demographic pressure being built around them because of changed economic and other conditions. This phenomenon, well recognised in central Europe, is spreading rapidly.

Mr President, it has given me much pleasure to once again address the Assembly, for which I retain great affection and great respect. The Council of Europe has given a very good account of itself, and has been a beacon leading generations of Europeans and other members of the international community to brighter and broader pastures.

I conclude by wishing the Council of Europe well. I foresee for it a continued inspiring role in the construction of a new and, perhaps, integrated Europe.

The President of the Assembly

Thank you very much for your interesting and inspiring statement, Mr Tabone. I am happy to note that you have been unable to avoid being one of us again. We have not only heard from Malta’s Head of State; we have heard from a parliamentarian and colleague who is concerned about issues that affect the Assembly. You may be sure that we shall take full account of what you have said.

Let me take this opportunity to send greetings to Mrs Tabone, who is present today and whose hospitality was much appreciated by members of the Assembly who visited your country last spring. I also extend our greetings to Mr de Marco, your Vice-Prime Minister and Foreign Minister. He is a staunch colleague, and a dear friend of most of us.

We are all particularly happy to listen to your speech, Mr Tabone; but we are also particularly happy to be able to praise your personality and, through you, to send our message to your country.

Among our audience are some youngsters: the coming generation of the Maltese people. They should be proud of their President, because we are proud of our colleague.