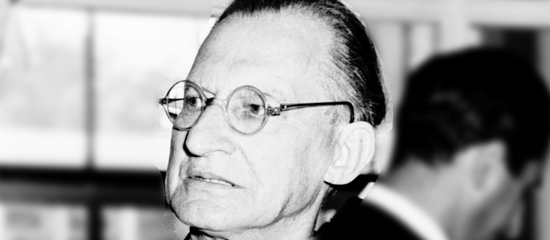

Alcide

De Gasperi

Prime Minister of Italy

Speech made to the Assembly

Monday, 10 December 1951

Mr President, I should like in the first place to thank you, and to thank the Assembly, for your kind invitation, which has given me this welcome opportunity of briefly setting forth the ideas and anxieties aroused in me by the grave problems with which we are at present confronted. It has been a great satisfaction to me to note that the ideas of which we in this Hall are the champions have recently been making considerable progress towards practical fulfilment. Despite the innumerable difficulties encountered, the Schuman Plan is on the verge of realisation. All the States represented here have, I think, now accepted the principle that some form of European integration must be achieved. Opinions differ only on the question of how this is to be done.

I believe I am correct in thinking that what you wish me to do is not to make a statement in general terms of my own opinion – which in any case is fairly well-known – but to give exact expression to my views regarding the concrete problem resulting from the urgent need for a common defence policy. The need for security has given rise to the Atlantic Pact – an organisation which is by way of restoring the balance of power. This is the first line of defence against the danger threatening us from without: it is based on the merging of individual national effort with collective effort.

But the essential condition of effective resistance against aggression from without is that Europe shall defend itself within, against a fateful heritage of civil wars – for it is thus that the wars of Europe must be regarded from the standpoint of world history: that alternation of aggression and revenge, of thirst for supremacy, of avid grasping after wealth and territory, of anarchy and tyranny, which have has been handed down to us by our common history, so glorious in other respects. It is, therefore, against these factors of potential disintegration and decline, of mutual suspicion and moral decay, that we have to fight with all our strength.

“... to bring together the purest ideals of the associated nations, that they may gleam in the light of a common flame ...”

We realise that it is for us to save ourselves, to save our heritage of common civilisation based on centuries of experience. For, while it is true that the Atlantic Pact encircles the world, it is no less true that in that world Europe preserves within itself the most ancient sources of civilisation and its loftiest tradition.

History, with its similarities and coincidences, its links which when broken are instantly forged anew, shows us that the uniting of our forces is likely to dispel the rancour in our hearts, and can give us peace within Europe, even before a defence pact is concluded as a guarantee of that peace. The pooling of our social, cultural, and administrative experience doubles the strength of our national potentialities, and preserves them from all danger of decline, by giving them fresh impetus towards the creation of a still more advanced and still nobler civilisation.

What is the choice before us in this present- day, post-War world? We all agree that our homes, our institutions, our civilisation must be defended in the hour of danger. But the rising generation, which is attracted by a coherent and dynamic view of life, hesitates before a choice upon which its very fate may depend – whether to return to the road that was ours before the war, a road strewn with claims and conflicts based on the moral concept of the nation as an absolute entity, or else to move onwards to the co-ordination of certain forces, at times ideal and rational, at times instinctive and irrational, in the hope that life may broaden further, and the brotherhood of man be extended far and wide.

Which road are we to choose if we are to preserve all that is noble and humane within these national forees, while co-ordinating them to build a supranational civilisation which can give them balance, absorb them, and harmonise them in one irresistible drive towards progress? This can only be done by infusing new life into the separate national forces, through the common ideals of our history, and offering them the field of action of the varied and magnificent experiences of our common European civilisation. It can only be done by establishing a meeting-point where those experiences can assemble, unite by affinity, and thus engender new forms of solidarity based on increased freedom and greater social justice. It is within an association of national sovereignties based on democratic, constitutional organisations that these new forms can flourish.

Now is the time for this aim to be made clear, to be defined and underwritten, even if it cannot be reached at a single stride, nor attained all at once in its manifold aspects. Only by offering now that constructive and enlightened vision can we attract the great mass of the people and infuse them with the ardent idealism that will be required; and, above all, it is thus alone that we can capture the imagination of the youth of Europe. It will no doubt be necessary to perfect instruments and technical expedients, to work out solutions of an administrative character; and our gratitude is due to those who undertake this task. These provide the framework; they will be what the skeleton is to the human body. But is there not a danger that they may fall asunder, unless the breath of life enters into them this very day and gives them life?

If we do no more than set up common administrations, without any higher political will, drawing life from a central organisation, in which the wills of the various nations can come together, to gain fresh decision and warmth in a higher union, there will be a danger that this European activity may prove, in comparison with the dynamic force of the individual nations, to lack warmth and spiritual vitality; it might even seem, at time§, to be mere superfluous and burdensome trappings, comparable to what over-burdened the Holy Roman Empire at certain periods of its decline.

In that case, the young people of Europe, hearkening to the clearer call of their blood and their homeland, would regard the European entity, if thus constructed, as an obstacle or as an incubus. In that case there would be an obvious danger of degeneration.

That is why, despite our clear awareness of the need to build this construction by gradual stages, we consider that while we are building it our action must always be such that the goal remains clear, definite, and generally agreed. That is all the more necessary when we come to pooling that essential and traditional instrument of national sovereignty, the army.

The armed forces of a nation are among its highest moral institutions; they are the school of the noblest military and civic virtues. Their banners are the reminder of past glories and the pledge of future sacrifices. If we are to require the armed forces of the different countries to merge together in a permanent and constitutional organisation and, should the need arise, to defend a greater fatherland, that fatherland must be visible, solid, and alive; even if its construction is not entire and perfect, the principal walls, at least, must be raised to view without more delay, and a common political will must be always on guard, in order to bring together the purest ideals of the associated nations, that they may gleam in the light of a common flame.

I am well aware that this European ideal has not yet taken a sufficiently strong hold on the public mind: there is only a group of politicians, intellectuals and idealists who are ready to turn aside from their constant preoccupation with the problems of their countries’ reconstruction, in order to devote their efforts to the preparation of a common future. You, the members of this Assembly, are among their number, through the trust that has been laid upon you by your colleagues, who, like yourselves, were elected by the people.

Now, although in Italy this idea has not yet been entirely accepted, and still remains to be thoroughly discussed in the Italian Parliament, I venture to express the hope that, in conformity with the spirit of its Constitution, the Italian nation, though diminished in power by the war, will be ready to agree to a reasonable limitation of its national sovereignty, in unison with the other European nations, if this will serve to widen the field of its creative activity.

The course which would be most logical, most practical, and most consonant with historical precedent would certainly be that of a Customs Union, and we, for our part, have settled the technical aspects of this problem with France, and look forward to its solution on the political level.

However, many roads lead to Rome.

Now, we are faced with the problem of the

European army, which, as I have already said, is a delicate problem, and touches the very core of each nation; I can do no more here, for the moment, than express my personal opinion, but I do not think that the Italian Parliament will refuse to give its approval to the meritorious effort of those generous and clear-sighted men who are striving to build a firm bridge between nations too often separated in the past by an abyss into which the whole of Europe has been plunged. That approval will not be withheld if the bridge is strongly built, rests on the pillars of public consent, and forms a real link between free and equal nations.

Clearly, therefore, the first and principal pillar must be a joint, elected, deliberative body, with powers even of decision and control, confined to those spheres which are governed in common, and exercising its authority through an executive “College”. The second pillar would be a common budget drawing a considerable part of its funds from individual contributions, that is to say, from a system of levies. I do not want to go into details, but I must say this! History teaches us that to meet common expenditure solely by means of national contributions may lead to dangerous disputes and even to ultimate dissolution. It would be less difficult for each State to transfer the proceeds of a monopoly, or of some type of single tax, to the common budget. Mr. President, this system seems to me to represent the minimum essential for this project to win the approval of the different Parliaments and the consent of the public. When this Army, thus organised and directed, has been incorporated into N.A.T.O., in accordance with the decision reached by the Rome Conference, we shall have united all our defensive forces, at the same time creating within Europe the nucleus of a federation which will be the surest guarantee of our democratic solidarity.

Mr. President, it is true that each of us has, in his own country, problems by which he is on every side beset; it is true, too, that some of us might prefer to carry on this work in other and easier spheres; but every one of us feels that this is an opportunity which will never return. It must be seized and given its logical place in history. That is why, after having paid my tribute to the courageous men: who have initiated this task and carried it forward, I say that it is now time for us all to resolve to complete it. It is essential that we should not fail in our task. We must enlist in our respective countries the co-operation of all democratic and socially progressive forces, and awaken in the hearts of all our friends, and particularly our American friends, renewed faith in the destiny of Europe.