1. Introduction:

forests as the basis of life

1. Plants are the basis of life.

It was plants which first made the transition from sea to land,

and they are the first link in the food chains on Earth – using

energy derived from sunlight they produce organic substances subsequently

ingested by animals and humans. Plants perform the most active role

in the oxygen cycle. Their huge biological mass gives the processes

of photosynthesis and respiration a tremendous impact on the gaseous

composition of the planet’s atmosphere.

2. Forests are the main type of plant life in many land biomes,

usually comprising one or more types of trees with a dense leaf

canopy. Forests are also places where herbs, shrubs, mosses and

lichens grow. The forest ecosystem is capable of sustaining itself,

and this is its key attribute. It means that a forest may live for much

longer than any of its trees. While trees may take root, develop,

age and die, old trees are succeeded by younger ones, and the forest

itself remains in its entirety.

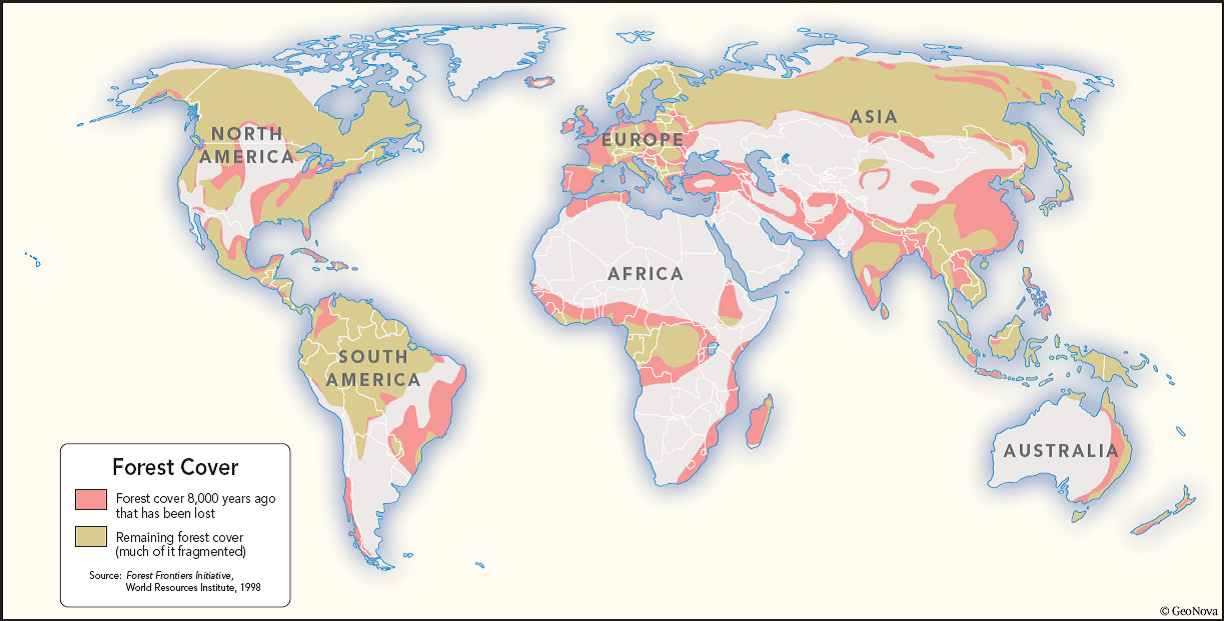

3. Forests may be needleleaf or broadleaf (or mixed), deciduous

or evergreen. They provide the living environment for many birds

and animals and are a source of timber, berries, mushrooms and raw

materials. Biomass accumulated within forests constitutes 90% of

all terrestrial biomass (representing between 1 650x109 and

1 911x109 tonnes of dry weight, with

coniferous forests accounting for 14% to 15% and rain forests for

55% to 60%). The world’s forests are therefore important carbon

stores.

4. With their important role in climate control and soil and

water protection, forests represent an important factor of biospheric

sustainability, and continuing efforts need to be made with a view

to their preservation and reproduction.

5. Forests have always been of great importance for humans. They

play a significant role in some modern economies, while also having

high environmental, social, cultural and recreational value in most.

It must also be noted and taken into account that large ancient

forests are homes to many indigenous human populations.

2. Role of forests in relation to global

environmental issues

6. The Earth’s forests perform

a number of essential environmental functions, for instance removing

and storing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere of our planet, preventing

soil erosion and controlling the water balance.

7. As we all know, forests have often been called the “lungs

of our planet”. While not a very accurate one, this is a metaphor

that does reflect the importance of forests in the global carbon

and oxygen cycles. Forest trees, like all green plants, perform

photosynthesis and produce organic substances, using atmospheric

carbon dioxide as a source of carbon and releasing oxygen back into

the atmosphere. One molecule of carbon dioxide taken in by a plant

(that is, one atom of carbon bonded to two of oxygen) corresponds

to one molecule of oxygen released back into the atmosphere. The

carbon bonded during photosynthesis (included in the organic substances

produced) is partially used by the plant for its own structure and

partially returned to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide during plant

respiration or decay. Thus the carbon used by the plant during its life

cycle for its own structure is equivalent to the amount of oxygen

that it has released.

8. Forests are so important as carbon stores because of their

huge biomass and the long-term storage of organically bonded carbon

in tree trunks. In boreal forests, for example, where decay is a

slow process, the trunk of a dead tree will take between 100 and

500 years to decay, that is, the carbon accumulated by a tree during

its life will be bonded for several centuries after the tree has

died. But in ancient forests where the biomass has stabilised and

decomposition rates are approximately the same as in primary production,

the annual amount of carbon bonded by photosynthesis is roughly

the same as the amount released during decomposition. In such conditions

the forests are not acting as carbon sinks any more, but remain

very important carbon stores for as long as their integrity is maintained.

9. It must be noted that in some cases the situation is more

complicated, and old forests retain their function as carbon sinks,

due to the accumulation of carbon in soil, for example. Furthermore,

some wet forest ecosystems such as wooded bogs show significant

permanent rates of carbon accumulation, even as ancient woodlands.

The very humid soils and resulting oxygen deficit prevent dead organic

substances from decaying. Such boggy soil accumulates dead organic

substances (peat) layer by layer, with the thickness increasing

as the years pass. The peat layers may be several meters thick –

between 3 and 5, and sometimes even up to 10 meters. Boggy forests,

like open, treeless peat bogs and many other wetland types, accumulate

peat over a period of thousands of years, bonding carbon dioxide

and releasing oxygen into the air. The accumulated carbon remains

bonded unless the bog is drained and oxygen is able to penetrate

the inner parts of the peat bed. At that point, the process goes

into reverse – the decaying peat releases large amounts of carbon

dioxide into the atmosphere; such releases may be particularly massive

in the event of peat fires, which are not uncommon in dry peatlands.

10. It is thus clear that any meaningful climate policy must take

into account the role of forests as carbon sinks and stores in order

to tackle a worldwide environmental challenge such as global warming,

given that it is excessive atmospheric carbon dioxide that causes

the greenhouse effect.

11. The role of forests in water protection is as well known as

their “lungs of our planet” role. Their importance for water protection

is not only recognised theoretically, but also put to practical

use: many countries have enacted forest legislation in order to

retain and preserve the forests which form a protective screen along

the banks and near the sources of rivers, streams and lakes. There

are relevant provisions of Russian legislation which require forest

screens to be created along all rivers, lakes and reservoirs of

any significance; the rivers which contain breeding sites of fish

used for commercial purposes have the widest forest screens. The

best-known aspect of the protective role of forests is their ability

to prevent the erosion of river banks, reinforce slopes and prevent

the development of gullies. If the slopes of a river valley and

the banks of associated streams are wooded, bank erosion takes place

on a significantly smaller scale – tree and other forest plant roots

bind the soil, preventing the formation of deep drainage lines;

thick forest litter, moss and lichen also protect the surface layer

of soil; dead tree trunks and branches lying on the ground and slight undulations

in the forest floor make the water take a more winding course and

flow less rapidly.

12. Forests may have a considerable impact on amounts of rain

and snowfall. It has been demonstrated that air is more turbulent

in forests, causing greater amounts of precipitation. Wooded river

basins may have considerably more rain and snow than treeless areas.

Moreover, forests can, in comparison to herbaceous vegetation, evaporate

significantly larger amounts of water (trees can recover water from

much deeper soils than can fleshy plants); in other words forests

return some of that water into the air, making the air more humid in

forests than in treeless areas when the wind is blowing.

13. Large-scale deforestation is among the main causes of increasingly

frequent disastrous floods, particularly in mountain areas, where

greater amounts of snow may melt in areas lacking vegetation.

14. Forests are able to reduce wind speed, prevent soil erosion

and accumulate moisture: these features are already being put to

good use today in order to address the very serious environmental

issue of desertification. One example of this can be found in the

People’s Republic of China, which has, since 1970, been carrying

out a governmental programme known as “The Green Wall of China”,

which entails the planting of trees to cover an area of 350 000

sq. km in order to prevent the Gobi desert from expanding. An objective assessment

of this large-scale reforestation effort would provide an important

source of information for those making similar efforts elsewhere.

15. Last but not least, the role of forests in maintaining global

biodiversity must be emphasised. Tropical, temperate and boreal

forests offer a diverse range of habitats for plants, animals and

micro-organisms. Consequently forests are thought to contain the

majority of the world’s terrestrial species. Forest biodiversity encompasses

not just trees, but also the multitude of plants, animals and micro-organisms

that inhabit forested areas. We can view that biodiversity at different

levels, including the ecosystem, landscapes, species and populations.

Complex interaction can occur within and amongst these levels. In

biologically diverse forests, organisms are thus able to adapt to

continually changing environmental conditions, and ecosystem functions can

be maintained.

3. Current

situation of forests worldwide

3.1. General

description

16. The estimated area covered

by the world’s forests is about 38 million sq. km. A slightly greater

proportion of them is in developing countries. It is estimated that

the world has lost about 5.5 million sq. km of forests, the total

loss of 6.5 million sq. km of forest areas (mostly in developing

countries) being set against an increase of 0.9 million sq. km.

Generally speaking, the reduction of forests is most visible in

developing countries, although the amount of that reduction seems

to have been lower than was predicted for the 1980s and 1990s, and

that downward trend continues.

17. Studies have shown that the main factors affecting forests

are agricultural development, in Africa and Asia, and major economic

development programmes associated with migration and with infrastructure

and agricultural development, in Latin America and Asia. In Asia,

the establishment of oil palm plantations has become a very important

driver of forest loss. Although timber production is not the main

cause of forest shrinkage, it is another important factor, especially

because logging operations in many areas were accompanied by road

building to make remote areas easily accessible for agricultural

colonisation.

18. The map below, produced by the WRI (World Resources Institute),

demonstrates the changes that have occurred in forest cover: it

shows the area covered by the Earth’s forests today as compared

to 8 000 years ago.

Figure 1: The Earth’s forests

8 000 years ago as compared to today. Forest cover that existed

8 000 years ago is shown in dark grey, and the forests still remaining

are shown in light grey

Table 1: Extent and causes of

forest reduction on the different continents according to the FAO

|

Continent

|

Forested area,

million

hectares

|

Rate of reduction,

hectares

per year

|

Main cause

|

|

Latin America

|

990

|

5-10 million

|

Logging

|

|

Africa

|

730

|

2-4 million

|

Logging, grazing

|

|

Asia

|

600

|

2-4 million

|

|

|

North America

|

580

|

40 000

|

Pollution

|

|

Europe

|

150

|

12 000

|

Pollution

|

19. The situation of the world’s

forests today cannot be described as good. Forests are intensively

logged and rarely regenerated. Annual logging removes over 4.5 billion

cubic metres. There is particular public concern worldwide about

tropical and subtropical forests, where logging accounts for over

half of global annual prescribed yield. Some 160 million hectares

of rainforests have already been destroyed, and only 10% of the 11

million hectares logged each year is regenerated through the planting

of homogenous forests. The rainforests which cover about 7% of the

surface in areas near the equator, in particular, are often termed

the “lungs of our planet”. They play an exceptionally important

role in adding oxygen to the air and absorbing carbon dioxide. Rainforests

provide a home for almost 4 million species. They are the habitat

of 80% of insects and two thirds of known plant species. These forests

produce one quarter of our oxygen reserves. Some 33% of the world’s

rainforest areas are in Brazil, while Zaire and Indonesia each have

10%. According to the FAO, these forests are being destroyed at

a rate of 100 000 sq. km per year.

3.2. The

forests of Europe

20. About 8 000 years ago, 70%

of European territory was covered by forests. They were almost everywhere,

other than in high-mountain, exposed or poorly drained areas. As

the population has grown and new equipment been developed, forest

logging has increased rapidly. Some areas have been cleared for agricultural

purposes, and the wood has been used for building or as fuel.

21. The forested areas of Europe (not including Russia) have now

shrunk to 68% of their original size, while only 1% of old forest

stands remain. Extensive forest areas remain only in northern Europe,

sub-Alpine regions and in the European part of Russia. A positive

fact, undoubtedly, is that in recent years the forest area in Europe has

grown by 4%, which is a greater increase than in any other part

of the world.

22. Russian forests play a key role in preserving global biodiversity

and biospheric functions, because it is there that the widest range

of natural ecosystems as well as considerable numbers of the different

species of the world are found.

23. Russia occupies a unique position in terms of the variety

of latitudes and zones which shape its biodiversity, because its

territory features clearly interlinked zonal natural ecosystems.

More than 180 native woody plants and shrubs, which form forests,

are known in Russia.

24. Within the European Union, forests exist in a great variety

of climatic, geographical and ecological conditions: in a temperate

or boreal climate, in Mediterranean or alpine zones or on plains.

Socio-economic conditions may vary considerably from one country

or region to another.

25. Europe’s forested areas are expanding faster than woodlands

are being lost to infrastructure and urban uses. This trend, which

began in the 1950s (and even earlier in certain countries), is attributable

to a variety of factors. Several countries have extended their forest

cover through planting programmes on uncultivated farmland. This

positive development distinguishes the European Union from the numerous

regions elsewhere in the world where deforestation continues to

reduce forest resources. It should be noted, however, that unless the

planting of forests is properly planned, it might harm agricultural

land of high natural value and destroy the habitats offered to flora

and fauna by open landscapes.

26. The importance of European forests for nature conservation

has been recognised in the context of the Bern Convention. Several

forest habitat types are listed in Annex I to Resolution No. 4 of

the Standing Committee of the Bern Convention and Annex I to the

EU Council’s Habitats Directive, and have to be protected in the

framework of the Emerald and Natura 2000 networks respectively.

4. Global

issues relating to the situation of forests

4.1. Forest

management

27. Forest management is one of

the types of natural resource management which is sustainable only

if it abides by a few simple principles:

- use of forests not exceeding their capacity for regeneration;

- preservation and strengthening of forests’ environmental

functions, role in the protection of water and other resources,

and other functions;

- management and conservation of forest biodiversity;

- allowing the use of forests in accordance with their relevance,

functions, location, and environmental and economic conditions;

- creating conditions for forest regeneration;

- compliance with science-based rules of use.

28. Forest resources can be used for many purposes, such as:

- harvesting of wood;

- harvesting of gum;

- tree sap collecting;

- haymaking;

- drug plants and raw materials for industry;

- forest grazing;

- location for bee hives and apiaries;

- gathering of wild fruits, berries, nuts, mushrooms and

other forest food resources;

- gathering of moss, forest litter, fallen leaves and cane.

29. Additionally, some forest areas may be used for field sports,

research, cultural and health purposes, tourism and sport.

30. Many governmental and international organisations have now

taken control of forest issues and, consequently, have an impact

on the forest industry and on pricing. One of these is the Intergovernmental Panel

on Forests (IPF) set up in April 1995 following the 1992 United

Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio

de Janeiro. The IPF works with international organisations, governments,

non-governmental organisations and the private sector. Its work

has a great impact on the forest situation and the forest industry.

31. The State of the World’s Forests (SOFO) report published by

the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) provides

regular information. The FAO’s Global Forest Resources Assessment

(FRA) is used as a basis for decisions by many other organisations.

And the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) engages in some activities

relating to the environmental role of forests and their protection.

4.2. Forest

industry

32. Forest products, production

volume, market conditions, prices and other relevant parameters

are directly linked with the situation of the world’s forests at

any given time, the environmental situation and global and national

forest management policies. Economic, political, demographic and

social trends determine forest management practices and have an

effect on the formulation of national policies and the establishment

of relevant institutions.

33. The quantity and extent of forests are mainly affected by

demographic changes (population growth and urbanisation), demand

for the forest industry’s products and the ability of forests to

perform important environmental functions.

34. Political trends which influence the forest sector include

decentralisation, privatisation, trade liberalisation and economic

globalisation.

35. While the total area of forest cover is in constant decline,

the demand for forest products is steadily growing. One of the most

important trends is the development of more efficient processing

technologies making better final output possible with the use of

a smaller quantity of raw materials. It is also important to shift

to more environment-friendly technologies.

36. The forest industry encompasses industrial timber and other

kinds of wood. The list of wooden products is very long. The forest

industry spans logging, timber processing, the production of pulp

and wood chips, the production of wooden containers, the construction

of wooden buildings and the manufacture of other wooden products.

37. Wood is subsequently processed to produce certain main types

of timber. Various industries use about 20 different techniques,

including sawing, milling, compression forming, forming, abrasive

treatment, drilling, chemical treatment, etc.

38. The main adverse consequence of poor forest management is

overlogging (more wood is logged than grows in any given year).

Overlogging leads to the depletion of forest resources. The world’s

forest resources are currently being overlogged. Forest resources

are renewable, but their regeneration takes on average between eighty

and one hundred years, or even more depending on forest type. If

overlogging occurs across wide areas, it can lead to the extinction

of species as a result of habitat loss.

39. A logging rate below the rate of growth leads to forest ageing,

lower productivity and diseases in old trees. So in order to maximise

the economic feasibility of the forest industry, foresters tend

to advocate forest management based on annual logging rates equal

to annual growth. It should be noted, however, that while logging

rates below the annual growth rate might not be economically rational,

they might be beneficial to biodiversity, as older forests tend

to provide habitats for greater numbers of species, especially rare

and endangered species.

40. Environmental problems are linked not only to the volume of

logging, but also to the methods used. A comparison of positive

and negative consequences shows that selective logging is more costly

but more environmentally friendly.

41. The forest industry provides raw materials for various uses,

from building to furniture to paper. Provided that these products

have a sufficiently long lifespan, they can potentially be regarded

as additional carbon stores. The overall climate-related assessment

of the forest industry, however, needs to be based on careful calculations

of the “carbon footprint” of the whole product life cycle.

42. The use of wood as a renewable energy source can also be part

of a sustainable forestry sector, provided that overlogging is not

allowed and the needs of forest biodiversity are taken into account

by those responsible for management. However, the replacement of

ancient forests with plantations of fast-growing tree species in

order to harvest these for biofuel is a typical case of “greenwash”,

since more carbon may be released as a result of the destruction

of old wood than is saved by replacing fossil fuels with renewables.

4.3. Forest

fires

43. Forest fires are amongst the

main abiotic factors contributing to ecosystem communities. Fire

is a natural part of the life cycle of some forest ecosystems, such

as the softwood forests of the south-eastern USA. In forests where

fires typically occur, older trees have a characteristic bark that

is resistant to all but the most destructive wildfires. Some types

of pine cones, for example, those of Pinus

banksians, once heated up to a certain temperature easily

release their seeds. In some cases fires lead to soil enrichment

by nutrients such as phosphorus, potassium, calcium and magnesium,

enabling grazing animals to find nutritious food. Thus measures

taken to prevent wildfires can result in changes to ecosystems,

as these depend on recurrent exposure of their vegetation to fire.

A build-up of unnatural quantities of unburnt debris in such forests

can lead to a risk of extreme wildfires. In forest ecosystems with

a natural tendency to catch fire, forest biodiversity to some extent

depends on files of low intensity.

44. However, the majority of forest fires nowadays are of human

origin. The statistics show that 97% of forest fires appear to be

caused by human beings, while only 3% are due to natural causes.

Both flora and fauna suffer from the fires, the vast majority of

which are started by human beings making careless use of fire or breaking

fire safety rules during agricultural activities. Debris-strewn

forests are at greater risk of fire.

45. Every year forest fires consume 2 000 000 tonnes of organic

substances. They also affect the forest industry, reducing the amount

of new growth, bringing about a decline in forest diversity, increasing

the numbers of trees damaged or uprooted by the wind, and causing

soil impoverishment. In addition, forest fires facilitate the spread

of harmful inserts and wood-destroying fungus. Frequent fires prevent

further succession and the natural return of forest cover.

46. In populated areas with intensive forest management, forest-based

enterprises use means such as fire alarm systems, chemicals, fire

stations, etc., in their efforts to safeguard forests as appropriate

from fire. Certain steps need to be taken in order to improve forest

fire resistance by providing forests with a fire suppression capacity:

set up a system of fire breaks and fire barriers, build up transport

infrastructure and water supply networks, and ensure that forest

floors are less strewn with debris.

47. Currently, forest fires are detected/located by fire detection

and observation facilities/posts, as well as through the use of

fire patrols on the ground and satellite monitoring. Ideally, an

operational system for monitoring fires from space would allow complete

coverage in real time of wildfires and their impact. When there

are high concentrations of smoke, airborne infrared detectors would

detect/locate burning areas of forest.

48. While improved fire-fighting technology will have an impact

on fire size, more public education and awareness campaigns on radio,

TV and other media are needed to reduce the number of fires occurring.

4.4. Forest

diseases

49. The second substantial cause

of damage and loss of forests is the occurrence of insect infestations

and disease, one of the greatest threats to forest health, forest

resources and biodiversity. While they are natural ecological processes

in forests, insect infestations and the spread of diseases are tending

to become more frequent as a result of inappropriate management.

Over the past ten years, the average surface area of the territories

in Russia that are constantly affected by insect infestation and

disease has been 5.37 million hectares. Mass reproduction of herbivorous

insects and the spread of diseases can cause forest losses of up to

190 000 hectares. Larger areas of forest succumbed to needle and

leaf-eating insects over the three years from 2005 to 2007, although

in 2008 this phenomenon decreased by 640 000 hectares as compared

to 2007, mainly due to a reduction in the size of planted areas.

50. There are several reasons for this situation: first and foremost

regular sudden arrivals of huge numbers of insects. In favourable

weather conditions insects breed more rapidly, and in most cases,

this leads to infestation. According to the data available for 2007,

Siberian forests, mainly in the oblasts of

Tomskaya and Irkutskaya, were the most severely affected by insect

infestations and diseases.

51. Among the recognised diseases fir canker is the most widespread

(445 000 hectares). In Siberia, outbreaks mainly occur in the oblast

of Kemerovskaya. General aggravation of the pathological situation

in Russian forests – leaving aside the particular biological characteristics

of some insects and diseases – results from an increasingly complex

range of adverse factors and institutional shortcomings in the functioning

of forest protection services, including a lack of specialists in

the field, underfunding of forest pathological studies and monitoring,

and insufficient forest pest control. The first of these shortcomings

can be addressed relatively easily, through better standardisation

and harmonised definitions.

52. To stabilise the pathological situation of forests, forest

protection services/forestry inspectorates engage in practical activities

to protect forests. Different methods and technical means are used

to fight insects and diseases, but none of them are universally

valid, capable of guaranteeing an integrated and wholly successful approach

against all types of insects.

53. Each year specific measures to fight insects and diseases

in designated outbreaks cover a total area of more than 500 000

hectares. The proportion of biological methods that include the

use of bacterial fertilisers and virus preparations may be as high

as 55%.

54. The fight against forest insects and diseases can be effective

and efficient only if it is of a systematic nature, involves all

appropriate means, is targeted on the appropriate types of insects

and diseases and is adjusted to the ecological, climatic and weather

conditions prevailing. It also needs to be borne in mind that, if the

measures adopted to eradicate forest pests and diseases are too

intensive, this can lead to a significant decrease of forest biodiversity.

4.5. Illegal

logging

55. As the new millennium advances,

illegal logging is on the increase. Furthermore, this increase entails breaches

of not only forest and environmental laws, but also the relevant

international conventions. Illegal logging results in huge forest

losses every year, as well as a further loss to the economies of

timber-producing countries. In many cases the proportion of illegally

produced timber far exceeds legal production. The illegal activity

depresses prices and undermines the profitability of legitimate

enterprises. In some countries illegal logging reaches the same

level as legal operations. In Indonesia, for instance, legal logging

amounted to 25-28 million cubic metresin

the late 1990s, while illegal operations lay somewhere between 17

and 30 million cubic metres(Natural Resources

Management programme, Jakarta).

56. In some countries there are even some senior government officials

engaged in illegal logging and other related illicit activities.

According to a study conducted recently in Cameroon as part of the

Global Forest Watch project, some high-level officials have amassed

natural resources portfolios including a very large illegal forestry

concession. It has also been alleged by several scientists that

in Brazil, particularly in the Amazon Region, 80% of all logging

is illegal. Not only tropical forests are subjected to illegal logging,

but boreal forests as well. One example is in British Columbia,

where, because of inadequate or non-existent supervision by the Canadian

forest agencies, excessive logging has become established practice.

There have been cases of logging within specially protected natural

territories in Poland and Belarus. Unfortunately, illegal logging

has become commonplace in Russia, where at least 20% of all logging

is either illegal or involves breaches of the law.

57. Illegal logging can be divided into the categories below:

a. Unlicensed (unauthorised) logging

57.1.1. Logging by the local population

– community logging – for non-commercial purposes (according to

rough estimates, such illegal logging accounts for between 8 000

and 10 000 cubic metresper year).

57.1.2. Logging by nationals or organised groups for commercial

purposes (illegal logging, depending on the region, varies from

16 000 to 500 000 cubic metresper year).

57.1.3. Logging by companies in areas where logging is not authorised,

but which are in proximity to either a designated area or an area

not readily accessible and difficult to monitor (illegal logging

is difficult to estimate and may account for hundreds of thousands

of square metres).

57.1.4. Overlogging in authorised and unauthorised areas.

57.1.5. Logging for unauthorised building on a non-forest site.

b. Licensed but illegal logging – Licensed logging could

be illegal if logging in the area concerned is also against the

law (the logging is not done in accordance with the terms of the

contract).

57.2.1. Authorisation for

logging was granted in an area which is protected by the law.

57.2.2. Authorisation for logging was granted in a case not in

accordance with, circumventing or infringing the forest regulations

in force.

57.2.3. Authorisation for logging was granted in a special area

following unlawful amendment of the relevant forest instruments.

57.2.4. Forest management is not in accordance with the law.

57.2.5. Logging affected by wrongful activities violating the

laws in force.

58. Illegal logging of high-value

timber exceeds 600 000 cubic metresin

Russia, equivalent in terms of value to 2 to 3 million cubic metres

of timber of lesser value.

4.6. Reforestation

59. Reforestation means regeneration

of legally logged forests and replanting of areas affected by illegal logging,

fires and other adverse conditions, and involves the planting of

new forests and an increase in woody species.

60. There are two kinds of reforestation activities: artificial

forestation (creating artificial stands by planting saplings or

seeds) and the encouragement of natural regeneration (involving

the reforestation of logged areas using trees which will provide

high-value timber, for example, mainly Picea and Pinus in taiga).

61. According to official statistics, 40% of logged territory

in Russia was subject to reforestation over the last two decades.

In most cases saplings aged between two and four years were planted

for the purposes of reforestation. This technique has the potential

to ensure a high survival rate, at the same time providing replacement

stands. Saplings are usually planted in small areas next to indiscriminately

logged taiga, so in the vicinity of logging roads (that is, easy

to monitor), whereas the remaining logged areas (90% to 95%) are

left unplanted, although some densely planted areas could be seen,

but only near urban areas.

62. Activities to promote natural regeneration involve the use

of seed trees or seed blocks, provided that seed trees are sufficient

in number and are spaced sufficiently far apart to allow for wind

dispersal. This practice has not always been followed, since such

regeneration measures often boil down to leaving damaged seed trees

without any commercial value which then fail to produce seed as

they die. Certainly, there have been some successful examples of

reforestation in forests of commercial value, where the forest situation

is more or less under control and where there are some, at least,

forestry activities (including logging and the planting of young

trees across greater or lesser areas). Moreover, reforestation of

coniferous forests may be successful in conditions that are unfavourable

for rapid growth of small-leaved trees (such as the most nutrient-poor

sandy or stony soils). However, there are few cases of successful

reforestation of high-value coniferous forests in the taiga zone

(in reality, no more than 5% of the total logging area), and these

do not play a significant role in overall forest development in

areas which have been logged.

63. Reforestation is carried out in many parts of the world, especially

in countries of eastern Asia, where it is used as a means of increasing

the forested area. The areas covered by forests have increased in

22 of the 50 most forest-rich countries. Asia as a whole gained

1 million hectares of forests during the period from 2000 to 2005,

and rainforests in El Salvador expanded by more than 20% between

1992 and 2001.

64. In the People’s Republic of China, where forest loss had been

widespread, the government adopted a law requiring every citizen

aged between 11 and 60 who is fit for work to plant between three

and five trees per year or do equivalent work in other forest services,

or to pay a corresponding amount of tax. The Chinese Government

states that about 1 billion trees have been planted in China since

1982. On 12 March each year, China celebrates Tree Planting Day.

The country has also begun a Green Wall of China project whereby

trees are planted in an effort to prevent expansion of the Gobi

desert. However, the high death rate of trees after planting (up

to 75%) has led to an acknowledgement that the project has not been

very successful. Since the 1970s, the overall area covered by forests

in China has increased by 47 million hectares. Some twenty years ago

only 12% of Chinese territory was forested; the figure today is

16.55%. While this is 4.55% higher, it is not a very high level

considering the stated quantity of reforestation activities.

65. The current growth of forest areas in Europe is largely the

result of the serious scientific approach adopted to reforestation,

but it should be also noted that a large proportion of the forests

planted in Europe are monocultures with little biodiversity. Worse

still, the proportion of these plantations for which alien species

are used is not negligible. Similar problems are found in other

parts of the world as well.

4.7. Forest

ownership

66. All over the world, ownership

issues arise in respect of forests, with title often non-existent.

67. When the EU had only 15 member states, approximately one third

of their forests and other woodlands were state property, as against

two thirds privately owned. The percentage in state ownership has subsequently

increased. While this change in the structure of forest ownership

was coming about, other changes were occurring in the professional

activities and lifestyles of private forest owners. In certain regions they

no longer derive their main income from forestry, their lifestyle

being increasingly city-based.

68. Although the percentage in private ownership has declined,

the number of private forestry businesses has nevertheless risen.

Some forests have been returned to their former owners in the EU’s

new member states, reintroducing the concept of private forest ownership

in those countries. There are, however, great variations in the

forest management skills and understanding of owners, in the size

of forestry businesses, in the expectations of forest management

and in the interest that it arouses.

69. The average size of public forestry businesses in the EU is

over 1 000 hectares, compared with just 13 hectares for private

businesses. The situation varies considerably from one country to

another, and most private owners hold less than 3 hectares. In this

respect, the structure of forest ownership in the EU differs from that

in countries elsewhere with large amounts of forest resources, where

the public ownership model is the most common, or even the only

one.

70. Brazil is the country with the most extensive tropical forests

in the world, and approximately 64% of its territory (some 544 million

hectares) is covered by woodlands of one kind or another.

71. Its natural forest surface area which can be used for timber

production is calculated to be 412 million hectares, of which approximately

124 million are in public ownership, including national forests,

indigenous reserves, national parks and other conservation areas.

The other 288 million hectares are mostly in private ownership.

It is estimated that 15% of the forest surface area potentially

usable for timber production is subject to permanent conservation

measures, for such purposes as riverbank or water source protection,

in accordance with the provisions of the country’s Forestry Code.

The forest surface area effectively available to supply timber is

thus of the order of 350 million hectares.

72. In Brazil, the national space research institute produces

annual deforestation statistics on the basis of between 100 and

220 photographs taken during the dry season by the Landsat satellite.

According to the institute, the biome of the Amazonian forest, originally

covering 4 100 000 sq. km in Brazil, had been reduced to 3 403 000

sq. km by 2005, representing a loss of 17.1%. Since 1970, the area

of tropical forest lost is equivalent to the size of Texas (and

larger than France). During the worst year for deforestation, 1995,

an area the size of Belgium was lost to a constant onslaught by

chainsaws and practitioners of slash and burn.

73. Former US Vice President Al Gore drew the wrath of Brazil

a few years ago when he said that Amazonia belonged to the world

as a whole. More recently, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula

da Silva denounced some British politicians who were encouraging

their fellow citizens to buy plots of land in Amazonia to save them

from exploitation. He proclaimed that Amazonia belonged to the Brazilians.

74. In the nine countries of Africa with the largest amount of

forest cover, almost every forest remains publicly owned. Official

figures indicate state ownership of 98% of the forest surface area.

75. There are several cases in which effective reform of forest

ownership in Africa is prevented by a lack of political will and

enthusiasm to recognise local and indigenous rights. Inadequate

preparation and execution of reform are also problematic, even where

indigenous populations’ and forest communities’ statutory rights

are recognised.

76. The precedence given by governments to industrial concessions

and conservation rather than the rights and subsistence of communities

has also curbed effective reform. Lack of clarity in ownership rules

has enabled governments to promote major concessions for logging,

oil extraction, mineral extraction, biofuels and other agricultural

products, to the detriment of forest populations.

77. Congo’s Minister for Sustainable Development has estimated

that expenditure of several billions would be needed just to find

out all about forest resources and draw up inventories.

4.8. International

initiatives for forest conservation and sustainable use

78. Both of the key global environmental

conventions signed in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 – the Framework Convention

on Climate Change and the Convention on Biological Diversity – entail

work on conservation and sustainable use of the world’s forests.

79. Questions arise today about how to distribute funds, which

body should be responsible for managing them, and whether it is

necessary to provide for a fund just for forests or to include forests

in what should ultimately become a major “green fund”, bearing in

mind that that the developed countries have made a commitment to

international funding of US$100 billion a year from 2020 onwards.

80. On 11 March 2010 the International Conference on the Major

Forest Basins was held in Paris, in an effort to consolidate and,

if possible, increase the early funding for forestry and climate

matters announced in Copenhagen and the national activities based

on the REDD+ mechanism announced by developing countries.

81. In a joint communiqué published during the Copenhagen Conference,

six states (Australia, France, Japan, Norway, the United Kingdom

and the United States) had announced their intention to allocate

a collective total of almost US$3.5 billion to REDD+ initial financing

for the period from 2010 to 2012, so that activities to combat deforestation

could be started immediately.

82. One of the major obstacles to the fight against deforestation

is the fact that a living tree is frequently of lower commercial

value than a felled tree. The mechanism for Reducing Emissions from

Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) is intended precisely

to remove this obstacle by assigning a financial value to forestry

emissions that have been prevented. The name REDD+ is used when

account is taken not only of prevented emissions, but also of forests’

carbon storage capacity and the good governance and planning of forests.

83. Several programmes have been set up to finance this mechanism.

Among them are:

- The United

Nations’ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation

in Developing Countries programme;

- Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative;

- The World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility.

84. Australia, France, Japan, Norway, the United Kingdom and the

United States have confirmed their joint commitment to the tune

of US$3.5 billion for the period from 2010 to 2012, while Germany,

Slovenia, Spain and the European Commission have joined this first

group of donors.

5. Conclusions

and recommendations

85. Present-day problems and the

unsatisfactory condition of the planet’s forests are the result

of a failure to make sound use of forest resources and forest management

(in both developed and developing countries), as well as slowness

to develop and deploy sustainable forest management techniques (including,

first of all, the kind of forest management and forest resource

usage which makes it possible to maintain not only forests’ productivity,

but also their biological functions, aesthetic and recreational

value, and landscape and biological diversity).

86. Today, forest fires, illegal logging, diseases and insect

activity in large areas pose a great problem for forests. All these

negative aspects are directly linked with human activity. It has

been established that only 3% of the forest fires recorded each

year are of natural origin, while the remaining 97% are caused by

human beings.

87. The areas worst affected by forest diseases and insect proliferation

are linked with those affected by human activities and not subject

to rehabilitation activities.

88. Illegal logging not only has a negative effect in terms of

forest destruction, but also has more far-reaching environmental

and economic consequences. Such logging is always brutal: no seed

trees are left at the logging sites, and the areas concerned are

subjected to pollution and uncontrolled growth of mono-dominant communities

(loss of biodiversity), lacking any species of no commercial value.

Afterwards, these areas usually become very prone to fire (being

strewn with debris) and to diseases and insect infestations (mono-dominant communities).

It is unsurprising that similar consequences are often seen in areas

which have been put to lawful use, but where the loggers subsequently

just pretend that they have carried out reforestation activities.

89. All the problems linked to negative conditions in forests

stem from the lack of due supervision of forest condition and forest

users’ activities, and from the differences between and imperfections

of forest legislation in various countries.

90. In this context, the following ways of dealing with the problems

that exist could be proposed:

- Creation

of a committee within an existing organisation (the UN, for instance)

to be responsible for the development, adoption and enforcement

of legislation designed to preserve and protect forests; development

and implementation of sustainable forest management (SFM) techniques.

- Development of international legislation (agreements)

on forest protection which are binding on all the countries with

significant forest resources which have ratified them.

- Development of proposals for payments in respect of every

unit of greenhouse gases, to be centralised by the committee that

is to be created and allocated for forest rehabilitation purposes

to countries which have forest resources, in proportion to the volumes

of greenhouse gases absorbed by their forests.

- Supervision of compliance with the requirements of such

new legislation within the committee that is to be created and monitoring

of forest condition should be carried out by the international environmental organisations

which exist in countries with significant forest resources, and

which will be registered (accredited) with the committee that is

to be created.