1. Introduction

1. Two weeks after my appointment as rapporteur by the

Committee on Political Affairs and Democracy, I attended, from 11

to 13 February 2013, the OECD Parliamentary Days, and in particular

the OECD High-Level Parliamentary Seminar on “Following the money:

Trade, tax and banks”. On that occasion, I also had the opportunity

to meet several high-level members of the Secretariat of the Organisation

for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and my compatriot,

Yves Leterme, Deputy Secretary-General of that organisation.

2. Following the exchange of views with Mr Leterme, I decided

to deal with the following subjects in my report: the OECD initiative

on New Approaches to Economic Challenges (NAEC); development and

taxation issues; and the OECD work on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting

(BEPS). I chose these topics for two major reasons. Firstly, it

is my view that governments’ inadequate responses to the economic

and employment crisis have damaged citizens’ trust in democracy.

This is demonstrated by the rise of populist propositions that characterise

public debate in many of our member States, and indeed it has been

the subject of a report recently presented to the Assembly.

Secondly, the ability of governments

to raise funds through taxation in order to pay for necessary public

services is a fundamental anchor for democracy. When the actions

of companies and individuals undermine governments’ legitimate financing

abilities, either through aggressive tax avoidance or through illegal

tax evasion, the very fundaments of democracy and equitable development

are threatened. This is a problem, not only for developed countries

but also for the developing world. The OECD is playing a leading

role in international efforts to bring greater fairness to tax policy

worldwide.

3. On 8 March 2013, I made a fact-finding visit to the OECD,

where I had very constructive meetings with: Sven Blondal, Head

of the Macroeconomic Policy Division, on Economic Outlook; Shardul

Agrawala, Head of the NAEC Unit in the Office of the Secretary-General,

on the NAEC; Grace Perez-Navarro, Deputy Director, Centre for Tax

Policy and Administration, on BEPS and the OECD work on Tax and

Development; and Willemien Bax, Head of Public Affairs, on OECD

activities relevant to the work of the Council of Europe. On 28 and

29 May 2013, I attended the OECD Forum in Paris, which focused on

three key themes in the debate on how to achieve a sustainable future:

promoting inclusive growth and addressing inequalities; rebuilding

trust in the system; and fostering sustainability.

4. In the meantime, I had proposed to the committee at its March

2013 meeting the following timetable, which is the same as we had

in 2012, and to which the committee agreed:

- Hearing with relevant OECD high-level officials and other

experts on 5 June in Paris, based on an outline report.

- The committee agrees on a draft report during the Assembly’s

June part-session.

- The draft report is sent to the overseas delegations and

to the OECD, for comments, at the beginning of July.

- Approval of the report by the Committee on Political Affairs

and Democracy, enlarged to include representatives of the overseas

delegations on 4-5 September in Paris.

- Debate in the enlarged Assembly on 1 October in Strasbourg.

5. On the basis of the above-mentioned agreed timetable and scope

of the report, I prepared an outline report for discussion at the

meeting of the Sub-Committee on relations with the OECD and the

EBRD in Paris on 5 June. On the occasion of this meeting, a hearing

was organised with the following participants: Raffaele Russo, Head

of the Non-Compliance Unit, International Co-operation and Tax Administration

Division, OECD Centre for Tax Policy and Administration; Shardul

Agrawala, Head of the NAEC Unit, OECD; John Christensen, co-founder

and Executive Director of the Tax Justice Network; and Gabriel Zucman,

PhD Candidate, Paris School of Economics.

6. In the light of this hearing and the outcome of discussions

with members of the sub-committee, I presented to the Committee

on Political Affairs and Democracy a draft report for consideration

during the June 2013 part-session, thus respecting the agreed timetable.

I took this opportunity to thank Mr Nicholas Bray for his valuable

assistance in the preparation of that version of the report.

7. The committee considered the draft report and agreed that

it be sent to overseas delegations and to the OECD for comments

or contributions. This was done on 5 July 2013. Some delegations

and the OECD sent contributions and I am grateful to them. Those

contributions which I could accept have been included in the present

report.

2. New thinking

needed to pull the world economy back on a growth path

8. The financial and economic crisis that exploded in

2008 is still continuing in 2013. Unprecedented action by central

banks to inject liquidity into economies has staved off disaster.

The tentative recovery that began in 2010 was not, however, strong

enough to put the world economy back on a solid growth path and

the outlook, particularly in Europe, remains uncertain. Unemployment

is high and businesses hesitate to invest. Consumers lack the confidence

to increase their spending and OECD governments are under pressure

to reduce high public debt levels.

9. According to the OECD’s latest economic forecasts, published

on 29 May 2013 ahead of the Organisation’s annual ministerial meeting,

the global economy is gradually regaining strength. The OECD predicted

that gross domestic product (GDP) in its 34 member countries would

grow by 1.2% this year, with the United States economy expanding

by 1.9% and the Japanese economy by 1.6%. Growth in China is forecast

to continue at a steady rate of 7.8% this year. However, European

economies mostly remain weak, dragged down by record-high unemployment.

The OECD forecast that the euro-area economy will shrink 0.6% this

year, before returning to a forecast growth rate of 1.1% in 2014.

10. Income inequality is rising, not only between countries but

within countries. According to recently published OECD figures,

the richest 10% of the population in OECD countries earned on average

9.5 times the income of the poorest 10% in 2010, up from 9 times

in 2007. The gap was largest in Mexico, where the richest 10% had

27 times more income than the poorest 10%. But it was also particularly

high in Chile, Turkey, the United States and Israel. Further cuts

in welfare spending are likely to add to income inequality and cause greater

poverty in OECD countries in the years ahead.

11. Against this background, it is not surprising that policymakers

are increasingly turning against the neo-liberal free-trade and

free-market policies that gained currency during the 1980s and 1990s.

In preparing this report, I was struck by the conclusions of the

latest Human Development Report from the United Nations Development

Program (UNDP). Entitled “The Rise of the South”, this report is

an invitation to shift from dogmatic thinking to fact-based thinking

on socio-economic policies for human development. It shows that developing

States that performed well were often those that actively supported

private industries and collaborated with the private sector to improve

human development; that opened gradually, rather than suddenly,

to world markets; and that invested in health, education and human

development.

12. This is in stark contrast to the dogmatic Washington thinking

of only a few years ago, which imposed on countries in difficulty

a recipe of minimal State intervention, immediate opening to trade

and structural adjustment with far-reaching cuts in public spending

on education and health.

13. This shift in policy approach coincides with a shift in the

nexus of growth from West to East and from North to South, and a

growing realisation that some economic recipes of yesterday are

no longer relevant for tomorrow. In an article in the OECD Observer last year, OECD Secretary-General

Angel Gurría acknowledged that “the world economy is going through

a paradigm shift”. Under such conditions, he concluded, “we need

to identify which of our previous ideas, frameworks and tools still

hold and which need to change”. Reality has forced the OECD to engage

in some serious soul-searching.

14. A look at some of the economic prescriptions that the OECD

was issuing only three years ago shows how far policy advice has

been overtaken by events. After the immediate financial crisis of

2008-2009 had passed, many developed countries responded with shock

treatment of spending cuts and tax increases in an effort to rein

in high public deficits. In its

Economic

Outlook 87, published in the spring of 2010, the OECD recommended

that the central banks begin exiting from extraordinary policy measures

and in some cases start to “normalise” their policy interest rates

in order to guard against a risk that inflation expectations might

become “de-anchored” in the context of a forecast recovery in activity.

At the same time, it suggested that the European Central Bank (ECB)

should prevent overnight rates from converging too soon to the higher

key policy interest rate and raise interest rates in the euro zone

by the end of 2010, this despite the fact that OECD’s models projected

low inflation for years to come.

15. In this context, one may note that the OECD has consistently

highlighted the role of structural reforms, not only in paving the

way for strong potential growth over the longer term but also in

strengthening activity in support of the recovery. Structural policies

are indeed at the heart of its analysis and policy advice and of

its response to the crisis.

16. Structural reforms were frequently cited as tools to combat

macro-economic imbalances and improve competitiveness for deficit

euro countries, both in the Economic

Outlook 87 and in subsequent publications, such as Going for Growth. Emphasis was put

on structural reforms in labour and product markets with the aim of

increasing competition, fostering innovation and combating long-term

unemployment. European periphery countries were cited in particular

as potential beneficiaries of such measures as part of a package

to restore competitiveness, but emphasis was also put on the need

for reforms in surplus countries that would contribute to a more

symmetric rebalancing.

17. In some instances, such as in the economic survey of Portugal

in 2010, a combination of lower labour taxes and higher value added

tax (VAT) was suggested as a way of giving short-term stimulus,

also called fiscal devaluation.

18. The OECD’s Economic Outlook 87 did

acknowledge that redressing imbalances through low inflation or deflation

in the periphery would be difficult and that not all countries should

pursue price competitiveness at the same time. The OECD’s advice

on monetary, fiscal and structural policy has reflected this, including

arguing for strong monetary stimulus to ensure that the inflation

target is met and allowing above-target inflation in surplus countries.

The advice differentiated on the pace of fiscal consolidation and

the urgent need for reforms in surplus countries, but it did not

follow up on that observation by recommending higher aggregate inflation

in the eurozone or fiscal stimulus in surplus countries as a means

of addressing imbalances.

19. Now, after three years of lacklustre growth and ongoing recessions

in many member countries, it is time to evaluate the forecasting

record and the impact of policy actions taken, including those recommended

by the OECD. Actual growth rates have turned out much weaker than

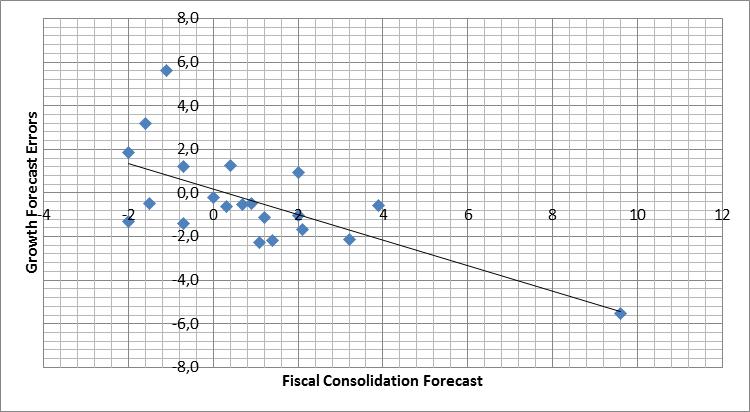

those forecast by the OECD and other such bodies in 2010. Figure

1 draws on OECD data to show the forecasting error, namely the difference

between forecast and actual GDP growth, as a function of the fiscal

consolidation effort that was predicted at that time. It turns out

that, on average, countries with large planned consolidation packages

have seen larger-than-expected adverse effects on growth. However,

the OECD argues that this result is very sensitive to the inclusion

of a specific country in the sample and does not necessarily imply

a causal link. In addition, other factors such as openness, financial

structure and the impact of the euro area sovereign debt crisis

appear to have stronger relationships to the forecast errors that

were made.

Figure 1: Fiscal consolidation

plans and growth forecast errors

Note: The sample used here includes

those OECD countries that are considered in the International Monetary Fund’s

(FMI) World Economic Outlook, October 2012, Figure 1.1.1.

20. Bond spreads in distressed euro countries have widened.

Figure 2 shows the rise in the spread of Spain, Italy and Belgium

from 2010 to 2012. It suggests a role of the rate increase by the

ECB in April 2011 in fuelling panic on European bond markets. By

reacting too aggressively to a perceived rise in inflation at that

time, the ECB may have implicitly given the signal that periphery

countries with overvalued real exchange rates could not count on

the ECB to help ease the deflationary spiral in these countries

by allowing for more inflation in the core. This led bond markets

to conclude that countries would not be able to maintain the deflationary

process for long, raising expectations of default and setting off

a self-fulfilling crisis. The ECB seems to have underestimated the

crucial importance in a monetary union of a lender of last resort,

in the form of a central bank that protects the government from

a sudden stop in access to funding.

Figure 2: 10-year bond spreads

over German Bunds, for Italy, Belgium and Spain

Note: The first line indicates

the date of the ECB’s rate hike, the second the inauguration of

the government Di Rupo-1 in Belgium.

3. The need for “new

approaches”

21. Why did this debacle occur? In part, because the

adverse effects of fiscal policy on growth were underestimated.

It turns out that the impact of fiscal multipliers – materialised

in the percentage decrease in GDP resulting from a given amount

of fiscal consolidation – has been higher than had previously been expected.

Now, at last, there are signs that Europe’s policymakers may be

coming to their senses and relenting on the pace of co-ordinated

fiscal policy tightening. Continued recession, rising unemployment,

sub-target inflation, and weak money and credit data have belatedly

forced the ECB to play a more active role in favour of expansion.

At the same time, the OECD has embarked on a far-reaching review

of economic thinking, under an initiative called “New Approaches

to Economic Challenges”.

22. If the crisis of 2008-2009 was the result of failing financial

markets, there are good reasons to conclude that the ongoing recession

after 2010 has been partly the result of bad judgment and policy

errors in dealing with the aftermath of the crisis and the legacy

of high private debt build-up. This initiative provides a welcome opportunity

to review new academic contributions that may help to formulate

policies better adapted to the current crisis.

23. Earlier this year, in my role as rapporteur, I had the privilege

to look at an OECD working paper setting out some of the considerations

that are guiding the OECD’s work. I was both surprised and gratified

to find phrases referring, for example, to “the need to revisit

the objectives of macroeconomic policies” and “the need to upgrade

the regulatory capacities of governments”. At one point, the paper

referred to the “flawed assumptions about the self-equilibrating

character of the economy”, while at another it noted “the need for policies

to be better oriented towards promoting well-being through reduced

inequality, better jobs and improved environment and not just macroeconomic

outcomes”.

24. New Approaches to Economic Challenges (NAEC) was launched

at the OECD in 2012 as an organisation-wide reflection process with

the aim of catalysing a process of continuous improvement of OECD analytical

frameworks and policy advice. Consistent with the ambitions of this

endeavour and to ensure a “whole of the house” approach, the Secretary

General himself is overseeing this work, with the support of his Chief

of Staff and Sherpa to the G20, Gabriela Ramos. While the financial

and economic crisis is an immediate catalyst, such a reflection

is timely for a number of other reasons as well, to adapt to evolving

policy challenges, including a further integration of large emerging

markets in the world economy; technological change; increases in

international division of labour; population ageing, migration and

other demographic shifts; and growing natural resource scarcity,

climate change and environmental degradation. A cross-cutting theme

in the NAEC initiative is the limitation of existing analytical

tools, policy frameworks and governance arrangements to address

the significant rise in interconnectedness and complexity of the

global economy. This includes interconnectedness across and within

countries, between the financial sector and the real economy, and

at a deeper level, among various global trends that have been building

up for decades.

25. The ultimate objective of NAEC is to develop a strategic policy

agenda for well-being and sustainable, inclusive growth built on

the interconnectedness, complementarities and trade-offs among different

policy objectives and instruments. Working within the NAEC framework,

and building on its flagship work on growth, inequalities and well-being,

the OECD aim to deliver a new vision that combines strong economic

growth with improvements in living standards that matter for people’s

quality of life – good health, jobs and skills, and a cleaner environment,

including from an intergenerational perspective. A critical element

in this agenda is the work on inclusive growth that was launched

at the OECD with the support of the Ford Foundation. In its May 2013

report to its annual Ministerial Council Meeting, the OECD set out

the objectives of its “New Approaches to Economic Challenges” as

being to:

- improve our understanding

of the complex and interconnected nature of the global economy and

find better ways to cope with policy trade-offs and profit from

synergies (such as between growth, inequality, stability and the

environment);

- recognise the importance of economic growth as a means,

but not as an end, of policymaking. This means having a broader

definition of well-being outcomes and developing policy outcomes

that combine strong economic growth with improvements in living

standards and outcomes that matter for people’s quality of life

(good health, employment, etc.);

- identify areas where OECD analytical frameworks need to

be adjusted or complemented; and examine the potential for mainstreaming

new economic data, tools and approaches (for example behavioural economics);

- enable governments to identify, prioritise and combine

reforms to support sustainable, inclusive growth.

26. If such statements are harbingers of a shift in economic thinking,

not just in relation to Europe but at a global level, there may

indeed be hope for a long overdue meeting of minds between North

and South in search of policies for a better shared well-being for

all the people of the world. I feel that the OECD is to be encouraged to

pursue its work on “New Approaches” with a view to bringing new

thinking to a debate that for too long has been going round in circles.

The world needs to break out of the bind that it finds itself in.

As a grouping of nations committed to best practices in economic

policy, the OECD is the right forum in which to take this debate forward.

4. Handling the liquidity

trap

27. In the meantime, however, we must not lose sight

of the harsh realities. One important observation with far-reaching

consequences that emerges from the OECD’s studies is the fact that

the crisis seems to have permanent effects on economies’ growth

potential. Not only are there short-term effects, with economies underperforming

at levels below trend: the long-term productive capacity of a country’s

economy is damaged. Economists call this effect hysteresis: the

long-term consequences of short-term effects.

28. There are numerous channels through which hysteresis works:

reduced capital investments, reduced investment in research and

development, reduced labour force attachment on the part of the

long-term unemployed, scarring effects on young people who have

trouble starting their career, reduction in governments’ physical

and human-capital investments. All have the effect of depressing

an economy’s potential. Even when the economy recovers, it will

find itself on a lower growth path then before.

29. Economists such as DeLong and Summers

have

pointed out that hysteresis adds an important new dimension to the

austerity debate. Indeed, it is clear that hysteresis endangers

the long-term viability of public finances since it puts the economy

on a lower growth path. The corollary of that observation is that

temporary fiscal expansion may be self-financing in the long run

if hysteresis effects are sufficiently strong. If there are moderate

to large fiscal multipliers, fiscal expansion will cause the economy

to grow in the short run. The hysteresis effect allows the short-run

boost to have long-lasting positive effects. Applying the model

to the eurozone, DeLong

states that if long-term real borrowing

costs in the eurozone do not exceed 5%, temporary stimulus will

probably strengthen fiscal conditions and improve confidence.

30. DeLong and Summers are careful to point out that this effect

only works in limited cases. As a first rule, interest rates must

be reasonable. Obviously, a government with acute liquidity problems

will not be able to finance a short-term fiscal expansion. Also,

fiscal multipliers must be reasonably high. DeLong and Summers argue

that this is not the case in most instances. In normal times, central

banks tend to offset fiscal stimulus through monetary tightening:

the fiscal expansion will not have any effect, multipliers are close

to zero.

31. In severe crises such as the one that we are living through

today, monetary authorities may not “lean against the wind” as they

do in normal times. Indeed, their tools are likely to be insufficient

to combat the crisis: this phenomenon is called a liquidity trap.

These conditions may characterise large parts of the western world today.

32. As your rapporteur, I should like to share some other considerations

that I have found interesting in preparing this report. The work

of Gauti Eggertson and Paul Krugman

has

shown that countries that need to cope with excessive debt may not

profit from policies that are otherwise considered as beneficial

for growth. They show that increased flexibility and an increase

in labour supply may even result in adverse effects. Falling prices

and wages due to these policies increase the real value of debt,

so that the burden of indebted households becomes even larger than

before. The cycle of debt deflation becomes even more vicious than before.

33. In a recent paper, Eggertson et al

apply

this framework to Europe. They find that structural reforms may deepen

the recession, worsening deflation and increasing real interest

rates. They suggest designing reform packages in such a way that

structural reforms kick in only when the threat of liquidity trap

has passed. They even suggest that

during the

slump structural reforms should be going in reverse, before being

implemented during normal times. Nonetheless, results are sensitive

to the credibility of the reforms announced and the ability of the

central bank to provide for policy accommodation. Likewise, OECD

analysis suggests that some reforms can have positive effects on

activity even in the short run depending on the nature of the reforms

and, as implied by Eggertson et al, the state of the economy.

34. A large debt overhang from speculative bubbles is a serious

problem for many periphery countries. Portugal, Ireland and Spain

in particular have seen a large build-up of private household debt

in the decennium preceding the financial crisis.

35. A shift from labour taxes towards VAT is sometimes presented

as another tool to redress competitive imbalances. Received wisdom

on this matter says that such an operation can have only temporary

effects: after a while, wages rebalance to restore purchasing power

which negates the pro-competitive effect. Some studies conclude

that these reforms only produce small effects for reforms with relatively

large budgetary sizes.

36. If consolidation is needed, the choice of tax instruments

to achieve it should take account of equity concerns as well, since

it turns out that economic contraction does not hit everyone in

the same way. Ball

et al.

show

that spending cuts, in addition to raising long-term unemployment,

hit wage-earners the most, while profit and rent income recover

rather quickly. These results suggest that an equitable consolidation

package should contain reforms that shift the tax burden away from

labour and towards capital income.

37. From this short review, it should be clear that the economic

challenges that lie ahead of us require carefully tailored policy

advice to make sure that recommendations fit the needs of the countries

in question. Both specific circumstances, such as the existence

of a large debt overhang, and the time period in question, including

the threat of a liquidity trap, should be taken into account.

38. But in the context of the European monetary union, the shared

responsibility of member States should be acknowledged too. If full-fledged

budgetary union is not possible, intermediate policies should be considered.

For instance, Paul de Grauwe

argues

that countries which have been able to stabilise their public debt-to-GDP

ratio should stop trying to balance their budgets and keep debt

ratios constant to the level of 2012.

39. The OECD has a vital role in providing policy advice, not

just to the governments of its member countries, but to the world

community at large. It has already drawn governments’ attention

to the challenges posed by widening income inequality in most countries,

and it has broadened its analysis of pro-growth structural reforms to

highlight trade-offs, synergies and unintended consequences of structural

reforms on the distribution of income within countries.

40. With the 2015 deadline for the Millennium Development Goals

close at hand, the OECD is working in the context of its Strategy

on Development to strengthen engagement and knowledge sharing with

developing countries. Continuous efforts are being made to mainstream

development into the organisation’s work and achieve Policy Coherence

for Development. In the environmental policy area, too, the OECD

is taking a lead role in offering guidance to governments. Its Green

Growth Strategy, launched in 2011, is now being mainstreamed into

core policy areas. The education work is also covering more and

more the realities of developing countries.

41. It is gratifying to see such examples as evidence that the

OECD is at last taking a much needed holistic approach to economic

policy issues. Specifically, it is taking this work forward with

its reflections on “New Approaches to Economic Challenges”, which

highlight the inclusive growth dimension of its policy advice. I recommend

that the enlarged Parliamentary Assembly urge the OECD to continue

in these endeavours with a view to presenting clear conclusions

at an early date.

5. Tax evasion and

aggressive tax avoidance: a threat to democratic institutions

42. As we have seen, the financial and economic crisis

is constricting governments’ ability to finance necessary health,

education, welfare and infrastructure spending. Fiscal pressures

are creating a political backlash, as citizen’s protest against

the double squeeze of recession and rising tax burdens. Revenue shortfalls

due to tax evasion and the aggressive tax avoidance practices of

multinational companies challenge democratic systems. It is to be

welcomed that the OECD is addressing these issues through its campaign against

tax havens and its work on BEPS.

43. More needs to be done, however, both to crack down on illegal

tax evasion and to promote far-reaching reform of tax systems in

order to combat aggressive tax avoidance. Governments have a duty

to ensure that taxes are levied both fairly and efficiently. Much

of today’s tax legislation is based on an outdated vision of economic

activity dominated by fixed assets and with limited cross-border

exchange. A digital economy, based on intangible assets and rapid

cross-border transfers, requires radical new approaches to taxation.

The OECD, given its mission to develop rules supporting the efficient

operation of global markets, provides an appropriate forum for the

elaboration of new approaches. What is needed now is forceful new

thinking, backed by the determination to act.

44. I view this as a matter of extreme urgency. In Europe, leaked

documents and e-mails concerning funds allegedly hidden in secret

accounts in tax havens by politicians, business people and other

wealthy individuals have undermined confidence in democratic institutions.

Tax evasion and tax avoidance deprive European Union governments

of around one trillion euros in annual revenues, according to the

European Commission. This exceeds the total amount that European

Union member States spend on healthcare and it amounts to four times

the amount of money spent on education.

45. European Council President Herman Van Rompuy put the issue

in stark relief ahead of the summit on 22 May 2013 at which European

Union leaders reaffirmed their commitment to crack down on tax evaders.

“Tax evasion is unfair to citizens who work hard and pay their share

of taxes for society to work. It is unfair to companies that pay

their taxes but find it hard to compete because others do not. Tax

evasion is a serious problem for countries that need resources to

restore sound public finances.”

6. Combating base

erosion and profit shifting

46. The issue is not just a matter of concern for developed

countries. Developing countries suffer massively from a fiscal haemorrhage

to tax havens. Nor is the issue just a matter of illegal tax evasion.

It also concerns fully legal practices that are used by multinational

companies to minimise their tax bills. In Britain, companies like

Amazon, Google and Starbucks have come under fire for accounting

arrangements that enable them to minimise legitimately the amount

of tax they pay to the United Kingdom Treasury, despite buoyant

sales on British soil. In the United States, Apple has been criticised

in Congress for avoiding taxes on tens of billions of dollars in

revenues from its international operations that were channelled

through offshore entities. In other countries, concerns are also

growing that multinational corporations are unfairly exploiting

cross-border accounting opportunities to maximise their profits

by reducing the amount of taxes that they pay.

47. At the heart of such operations is a clever manipulation of

the so-called “arm’s-length principle”, a concept long considered

as a core element in efforts to maintain a level fiscal playing

field for international businesses. This arm’s length principle

requires different entities within a multinational group to book transactions

between them as if they were independent enterprises for tax purposes.

It was conceived as part of a construct to help promote cross-border

business by eliminating the double taxation of profits.

48. Recent examples of corporate activities such as those mentioned

show, however, that the construct has undergone such a monstrous

distortion that in many cases it actually results in artificial

profit shifting. The much vaunted level playing field has become

a rock-strewn, crater-pitted terrain in which the skilful and unscrupulous can

easily outmanoeuvre tax inspectors armed only with outmoded rule

books.

49. What is needed now, in addition to a crackdown on tax evasion,

is wholesale tax reform. In my view, merely tinkering with the present

system will not suffice to address the fiscal challenges facing

Europe and the entire world. In the United States, President Barack

Obama acknowledged as much in the President’s Framework for Business

Tax Reform, a joint report published in February 2012 by the White

House and the US Treasury. “The empirical evidence”, this report

stated, “suggests that income-shifting behaviour by multinational

corporations is a significant concern that should be addressed through

tax reform”.

50. G20 leaders have taken up the challenge, stating “the need

to prevent base erosion and profit shifting” in the final declaration

following their June 2012 summit in Mexico. Responding to a request

from G20 finance ministers, the OECD published a report entitled

“Addressing Base Erosion and Profit Shifting” in February 2013.

This report, which analyses the root causes of base erosion and

the reasons why profit shifting takes place, identified a number

of technical elements linked to accounting procedures that facilitate

these practices. They include hybrids and mismatches which generate

arbitrage opportunities; the residence-source tax balance, notably

in the context of digital transactions; and intragroup financing,

whereby companies in high-tax countries are loaded with debt; and

transfer pricing issues, such as the treatment of intangible, group synergies,

and location savings.

51. Hybrids, for example, exploit the possibility of having the

same money or transaction treated differently by different countries

to avoid paying tax. Typical examples include hybrid instruments

allowing a company to treat something as debt in one country and

equity in another and hybrid transfers that treat a transaction

as transfer of ownership of an asset in one country and as a loan

with collateral in another. In my view, the enlarged Assembly should

welcome this analysis and urge the OECD to follow through with clear

proposals for reform.

52. The OECD Secretary-General presented “Addressing Base Erosion

and Profit Shifting” at the February 2013 Moscow G20 meeting of

finance ministers, who expressed strong support for the work done

and urged the development of a comprehensive Action Plan. The Action

Plan was developed by the OECD Committee on Fiscal Affairs between

February and June 2013. Non-OECD G20 countries participated in this

work and they were all present at the meeting held in Paris on 25

June 2013 where the Action Plan was approved by the Committee on

Fiscal Affairs. The Action Plan was presented to the G20 finance

ministers’ meeting of 19 July 2013, where it received unprecedented

support.

53. The ambitious Action Plan sets forth 15 actions to address

BEPS in a comprehensive and co-ordinated way (for a summary, see

Annex). These actions will result in some of the most fundamental

changes to the international tax system since the 1920s and are

based on three core principles: coherence, substance and transparency.

The Action Plan also calls for further work to address the challenges

posed by the digital economy. Looking towards innovative approaches

to deliver change quickly, the Action Plan calls for a multilateral

instrument which countries can use to implement the measures developed

in the course of the work.

7. Who is to blame?

54. At the same time, it is to be noted that tax avoidance

cannot just be blamed on the aggressive strategies of individual

companies; it is also the result of the tax policies of national

governments, including those designed to attract investment by foreign

corporations.

55. The OECD’s February 2013 report warned that the effectiveness

of anti-avoidance rules was often reduced as a result of heavy lobbying

and competitive pressure. It also pointed an accusatory finger at preferential

regimes which lure companies to more attractive tax locations with

only minimal benefit to the receiving host country and significant

tax base erosion elsewhere. Those familiar with the issue acknowledge that

there has been hypocrisy on the part of governments in complaining

about erosion of their tax base while offering tax advantages to

foreign companies.

56. Following on from its February 2013 report, and for purpose

of developing the Action Plan which was presented to G20 Finance

Ministers in July 2013, the OECD consulted a range of stakeholders

in March and April 2013, including business and industry, through

the Business and Industry Advisory Committee to the OECD (BIAC),

labour unions, represented by the Trade Union Advisory Committee

to the OECD (TUAC), civil society organisations and non-governmental

organisations (NGOs). While business and industry representatives

expressed predictably nuanced views of the issues raised, the representatives

of the labour movement and civil society made no bones about their

concerns.

57. In a report entitled “No More Shifty Business”, 58 NGOs from

across the world greeted the OECD analysis as “an urgent call to

design a new international tax system that: (i) redresses the current

unjust distribution of the global tax base, (ii) treats multinational

corporations (MNCs) as what they really are: complex structures

that are bound together by centralised management, functional integration

and economies of scale, and (iii) makes MNCs pay their taxes where

their economic activities and investment are actually located, rather

than in jurisdictions where the MNC’s presence is fictitious and

explained by unacceptable tax avoidance strategies.”

58. In a subsequent follow-up comment, which I think is worth

quoting

in extenso, this group

stated as follows:

“Base erosion

and profit-shifting result from a deep structural flaw in the international

tax system, and is indeed a major cause of the instability of that

system. This flaw is the failure to treat multinational enterprises

according to the economic reality of their activity. Instead, a

principle has become gradually entrenched that they should be taxed

as if they were operating as separate enterprises in each country dealing

independently with each other. This fiction does not merely allow

but encourages multinationals to organise their affairs by forming

entities in suitable jurisdictions to reduce their overall effective

tax rate.

The systematic tax avoidance which results from this basic

structural flaw has many extremely harmful results. Governments

and tax authorities are rightly concerned by the immediate revenue

losses, but the ramifications go much wider:

systematic tax avoidance by the largest and most powerful

companies in the world undermines the legitimacy of taxation everywhere,

as the February report on BEPS acknowledges;

it gives the multinationals which exploit these avoidance

opportunities very significant competitive advantages over national

firms, resulting in inefficient allocation of investment and major

distortions to economic activity;

at the same time, it distorts the decisions of these firms

themselves, resulting in some benefits to some countries but overall

economic welfare losses;

it has particularly distorted the finance sector, greatly

contributing to the creation of shadow banking, excessive leverage

and other techniques, and hence the financialisation of economies,

leading to the bubble which caused the financial crash of 2007-9,

and the economic devastation that has followed;

it sustains the international tax avoidance industry,

resulting in enormously wasteful expenditures for both firms and

governments;

the techniques and facilities devised by the tax avoidance

industry, using the `offshore’ tax haven and secrecy system, are

also used for all kinds of evasion, not only of taxes, including

money-laundering for crime, corruption and terrorism;

Base erosion and profit-shifting, and generally tax avoidance

and evasion, seriously undermine efforts to tackle poverty and inequality,

including official development aid.”

59. As such considerations demonstrate, national governments are

going to have to review many aspects of their tax policies. We should

neither underestimate the complexity of this challenge nor the urgency

of dealing with it. In particular, governments need to ensure that

the international rules for the taxation of MNCs are thoroughly

reformed so as to adequately reflect production and trading practices

in today’s global economy. The enlarged Assembly should thus call

on the OECD to take a determined lead in moving this process forward.

8. Time to consider

“unitary taxation” of transnational corporations

60. In particular, more attention should be paid, in

my view, to the distortions that arise as a result of the present

application of the arm’s-length principle. The “separate entity”

approach gives MNCs tremendous scope to shift profits around the

globe to suit their own affairs. The OECD has sought to address

weaknesses in the system through enhanced co-operation and co-ordination

between governments, as well as changes to the OECD Transfer Pricing

Guidelines to ensure that the rules achieve the desired effect.

61. However, some commentators have suggested that it is time

to give closer consideration to proposals for unitary taxation of

MNCs, whereby these are treated as single entities. Under such an

approach, MNCs would be required to submit a single set of worldwide

consolidated accounts in each country where they have a business

presence, apportioning a share of their overall global profit to

each country in accordance with a weighed formula that would reflect

the true nature of their economic presence. Each country would be

able to see the full picture provided by such a report and tax its

portion of the global profits at its own rate.

62. This approach, in my view, could offer a number of important

advantages. By simplifying tax administration, it could cut the

costs of compliance for firms; it could align tax rates more closely

to economic reality, improving the fairness and transparency of

the international tax system; and it could greatly reduce opportunities

for international tax avoidance through profit shifting and the

use of tax havens. All of these outcomes would help to create a

genuine level playing field for businesses and would particularly

benefit developing countries that are frequently disadvantaged by

current practices.

63. Advancing towards such a goal will not be easy. As long ago

as 1935, the League of Nations concluded that unitary taxation was

“politically impossible”. At the OECD, officials involved in international

tax policy discussions suggest that such an approach would not be

feasible in today’s environment where tax policy is a matter for

decision by sovereign States. Nonetheless, experience in the domain

of international tax policy does show that comprehensive change

can be achieved. It should be noted that the Action Plan published

by the OECD and endorsed by G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank

Governors in July 2013, recognises that if the arm’s-length principle

is not fit to address the transfer pricing issues associated with

intangible assets, risk and over-capitalisation issues, measures

that go beyond it will be proposed.

64. Article 26 of the OECD Model Tax Treaty provides for exchange

of information on demand as the minimum standard for the bilateral

treaties to be signed by member States, but allows for all forms

of exchange of information, including automatic exchange, as explained

in the Commentary to the OECD Model Tax Treaty. The OECD has worked

on automatic exchange of information for many years and many OECD

member countries already routinely engage in automatic exchange

of information on a number of items of taxable income, as reflected

in the OECD Report, “Automatic Exchange of Information: What it

is, How it Works, Benefits, What Remains to be Done”, which was

welcomed by G20 Leaders in 2012.

65. In July 2013, G20 Finance Ministers declared automatic exchange

of information as the new global standard. I note with satisfaction

that the OECD is at the forefront of promoting it internationally,

is advancing on the design of a single global standard for multilateral

and bilateral models for automatic exchange of information, and

that its Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information

for Tax Purposes, which currently has 120 members, has been tasked

by the G20 to monitor and review its effective implementation.

66. With respect to efforts to ensure the fair taxation of MNC

earnings, I suggest that the enlarged Assembly should call on the

OECD not to close the door on unitary taxation, but rather to consider

a step-by-step approach which should start with the obligation for

MNCs to produce comprehensive global financial reports including

country-by-country reporting. Once this has been achieved, further

steps could be considered, including possibly the adoption of the

unitary taxation approach at the level of regional groupings such

as the European Union, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations

(ASEAN) and Mercosur, as a prelude to more widespread adoption.

67. In this connection, I further suggest that the enlarged Assembly

should call upon the OECD to do more to associate developing countries

with the work on BEPS. I note that the OECD has set up focus groups

to discuss key aspects of the issues at stake (Countering Base Erosion,

Jurisdiction to tax and Transfer Pricing). The OECD notes that countries

were invited to volunteer and that the focus groups were constituted

on that basis, with most countries’ requests being accommodated.

However, the participants in these focus groups are exclusively

drawn from OECD or G20 membership. As rapporteur, I feel it is important

that provision be made for smaller developing countries also to

have a voice in such forums.

68. In order to facilitate greater involvement of major non-OECD

economies, in the framework of the Action Plan, the “G20/OECD BEPS

Project” has been launched with G20 countries that are not OECD

members participating on an equal footing. Other non-OECD non-G20

countries can also be invited to participate on an ad hoc basis.

Moreover, the OECD’s outreach programmes will be used to involve

developing countries in the work. In particular, the four Global

Fora on Tax Treaties, on Transfer Pricing, on VAT, and on Transparency and

Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes, will be useful platforms

for developing countries to provide relevant input, as will the

Task Force on Tax and Development. In addition, the Committee of

Fiscal Affairs (CFA) will benefit from the input of the United Nations,

which has been a participant to the CFA since January 2012.

9. Stepping up the

fight against tax havens

69. In parallel, I believe that the enlarged Assembly

should urge the OECD to step up its fight against the widespread

illegal tax evasion that continues to be encouraged by tax havens.

In particular, the enlarged Assembly should support the OECD efforts

to press internationally for the implementation of arrangements

for automatic exchange of information for tax purposes in order

to combat illegal tax evasion.

70. The OECD has highlighted that automatic exchange of information

can help to counter offshore non-compliance in a number of ways.

It can provide timely information in cases where tax has been evaded

either on an investment return or the underlying capital sum. It

can also help detect cases of non-compliance even where tax administrations

have had no previous indications of non-compliance. Finally, it

has a deterrent effect, increasing voluntary compliance and encouraging

taxpayers to report all relevant information.

71. In this connection, the enlarged Assembly should welcome the

progress achieved so far on transparency and exchange of information

on request through the work of the Global Forum on Transparency

and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes and of the Forum on

Tax Administration. Set up by the OECD in 2000 to agree global tax

standards, the Global Forum now has 120 member countries and jurisdictions.

Since 2009, when the G20 launched its crackdown on tax havens by

calling for the effective implementation of internationally agreed

standards of exchange of information on request, the Global Forum

has published 113 peer review reports.

72. Progress has been achieved, in particular, in the number of

bilateral agreements between jurisdictions for the exchange of information.

Five years ago, most exchange of information on request took place

on the basis of a network of tax treaties between jurisdictions

with a long history of exchange of information. Today, there are

over 850 bilateral tax information exchange agreements (TIEAs) worldwide.

73. At the same time, the OECD’s move in 2011 to update and expand

the joint Council of Europe/OECD Convention on Mutual Administrative

Assistance in Tax Matters (ETS No. 127) has resulted in a more than doubling

of the number of signatories and a further increase in exchange

of information (EOI) relationships, including 228 new EOI relationships

where no bilateral agreement previously existed. Overall, the number

of new EOI relationships (bilateral and multilateral) has increased

by more than 1 100 since 2009. It should be noted that the convention

provides a useful and efficient mechanism for rapid implementation

of automatic exchange of information.

74. While some members of the Global Forum still have to remedy

deficiencies in their legal frameworks, it is worth noting that

most jurisdictions have now qualified at this level and are able

to move to Phase 2 reviews looking at the effectiveness of their

information exchange practices. In this phase of its work, the Global

Forum will start rating countries’ implementation of the standards

on the basis of a four-tier classification system: “compliant”,

“largely compliant”, “partially compliant” and “non-compliant”.

A first set of reviews covering around 50 tax jurisdictions will

be completed by the end of this year.

75. In parallel, the enlarged Assembly may take note of the outcomes

of the meeting in Moscow on 16-17 May 2013 of heads of tax administrations

from 45 economies in the framework of the Forum on Tax Administration,

and in particular of the work by the Forum’s Offshore Compliance

Network, which has been sharing ideas, tools and techniques for

tackling offshore tax evasion.

76. Some countries have been particularly effective in collecting

and using data about cross-border financial transactions to detect

offshore tax evasion. The tools and techniques that they have developed

have been documented in a guide that is available to network members.

This is complemented by a practical guide for international auditors

that allows them to understand the codes used by banks when making

cross-border transfers to identify the bank accounts involved in

the transactions. In addition, the Network has developed a catalogue

listing tactics, illustrated by practical examples, to help its

members develop and refine their strategies for dealing with offshore

tax avoidance and evasion, particularly in connection with the investigation of

complex offshore structures.

77. Despite such advances, however, I believe that more needs

to be done to combat the scourge of tax havens. In 2008, according

to a study by Gabriel Zucman,

of

the Paris School of Economics, around 8% of the financial wealth

of households worldwide, or the equivalent of around six trillion

dollars, was held in tax havens. Not only are vast amounts of capital

sheltered from domestic tax authorities, leading to substantial revenue

loss for strained government budgets. Offshore financial centres

no longer fit with a political environment which, in the wake of

the financial crisis, puts ever more weight on transparency and

regulation of the financial sector. In today’s world, tax havens

are increasingly seen as aberrations.

10. The need for a

“Big Bang” approach

78. Evaluating the effects of policy changes on the capital

flows between offshore financial centres and other countries is

by its very nature extremely difficult. However, a study by Zucman

and Niels Johannesen,

of

the University of Copenhagen, has thrown up some very interesting

information. Using data from the Bank of International Settlements

(BIS), they were able to track the behaviour of bilateral bank transfers

between 14 jurisdictions, including Switzerland and Luxembourg,

on a quarterly basis.

79. The results of their study shed light on the movements of

deposits from and between tax havens as the result of treaties signed

by tax havens with OECD countries. Tax evaders seem to have responded

to the signature of such treaties with only limited repatriation

of funds. This suggests that many tax evaders did not perceive a

big increase in the probability of being detected as a result of

a treaty.

80. Those that did respond to the signature of such treaties did

not, for the most part, repatriate their funds to their home country,

but instead shifted them to other tax havens that had not signed

such treaties. Indeed, after the G20 initiative of 2009 to crack

down on offshore tax evasion, the total value of deposits in tax

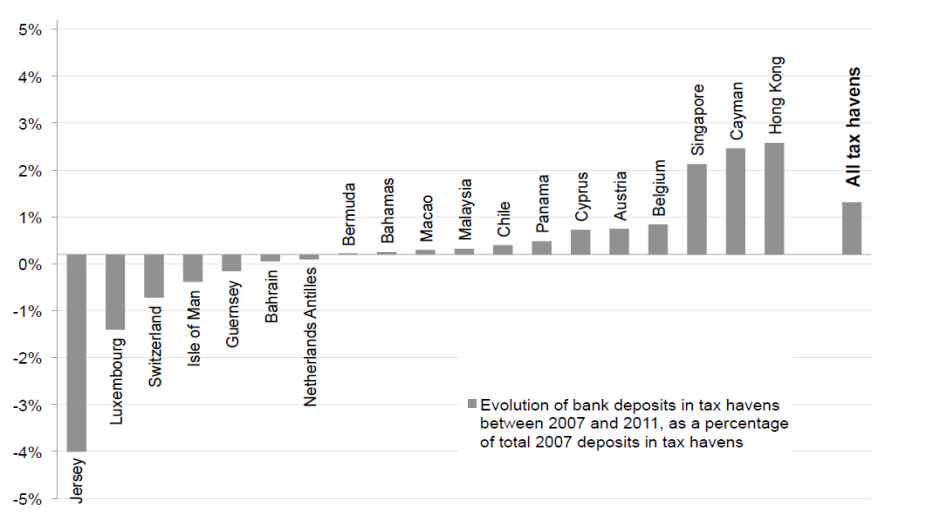

havens actually increased, with evidence of a moderate relocation

of deposits between tax havens. This is shown below in figure 3.

Figure 3

Source: Johannesen, N. and Zucman,

G. (2012).

81. The OECD states that it is too early to draw firm

conclusions from these data, since many of the 1 100 new exchange

of information arrangements are only now coming into effect, meaning

that their impact will not become apparent until countries begin

using them extensively. Nonetheless, I consider that the findings

of Johannesen and Zucman expose the limits of the gradual approach

advocated thus far by the G20 and the OECD.

82. The OECD has taken a commendable lead in formulating a policy

response to the phenomenon of offshore tax evasion. Its approach,

however, and that of the G20, has been to rely on soft, incremental

reform. So-called unco-operative financial centres were whitelisted

after signing 12 bilateral treaties for exchange of information,

freeing them from possible threatened sanctions. Even once such

a treaty has been signed, information exchange is not automatic:

the current standard of exchange calls only for information on request. Tax

evaders exploit loopholes left by the current approach, giving tax

havens an incentive to keep the number of treaties signed to a minimum.

83. In addition, the findings of Johannesen and Zucman demonstrate

the limitations on governments’ ability to track fund flows and

illegal tax evasion. Funds are frequently hidden in opaque corporate

structures, such as trusts or foundations, which conceal the identity

of their ultimate beneficial owner. So-called “secrecy jurisdictions”

use legislative and regulatory arrangements designed to reinforce

such concealment in order to attract non-compliant capital. In my

view, current evidence suggests the need for concerted action on

a number of fronts.

84. As your rapporteur, I would like to stress that the bulk of

the paper mentioned in footnote 13 is devoted to conducting an econometric

analysis that identifies the causal effect of signing on request

information exchange treaties on offshore deposits, all other things

remaining constant. The key conclusion is that nothing much happens.

Since they are on request, information exchange treaties are simply

not putting tax evaders in danger; hence the latter do not react

much. Those (a small minority) who do react simply move their deposits to

non-compliant tax havens. That is what the data say, based on a

rigorous methodology that controls potentially confounding factors.

85. I think it is essential to stress once again that there is

a real, crucial difference between on request information exchange

and automatic information exchange. There is very little information

exchanged today through over 800 existing treaties. The French tax

administration for instance receives information on about 50 offshore

bank accounts per year through its numerous treaties. But French

residents have at least 100 000 (and more plausibly 200 000 or 300 000)

offshore bank accounts. Automatic exchange of information would mean

receiving information about each of those accounts every year –

so 200 000 records or so, as opposed to 50 or so today. That is

a huge difference. It simply means that 99.98% of the work remains

to be done.

86. Experience shows that a concerted drive by major countries

can have an impact. In April 2009, when the launch of the G20 initiative

appeared to threaten non-compliant jurisdictions with financial

sanctions, tax havens moved fast to sign the treaties that were

required of them. Small matter that these treaties turned out not

to have the force that was expected of them. Nonetheless, the power

of concerted action was demonstrated. I am therefore pleased that

the OECD and G20 are leading the way in the implementation of a single

new global standard of automatic exchange of information.

87. In July 2013, the G20 declared automatic exchange as the new

global standard, called on all jurisdictions to commit to this standard

and tasked the Global Forum to monitor and review its effective

implementation. The G20 also stressed the need to assist developing

countries in implementing the new global standard. Other relevant

OECD initiatives like the “tax inspectors without borders” were

also highlighted by G8 leaders at the 2013 Summit in Loch Erne (Northern

Ireland).

88. At the same time, governments need to review basic nuts-and-bolts

aspects of their tax-reporting arrangements, including for example

the standardised use of fiscal identification numbers, in order

to make information exchange effective. On 18 June 2013, the OECD

made public a report prepared for the G8, entitled “A Step Change

in Tax Transparency”, setting out some of the practical steps that

would need to be taken in order to make automatic exchange of information

a reality. This report will feed into further discussions at the level

of the G20.

Also, at the July 2013 G20 Finance

Ministers’ meeting, the OECD was asked to submit in November a progress

report on the development of a single global standard for automatic

exchange, including a timeline for completion of the work in 2014.

89. In my view, in order to combat illegal tax evasion, there

is a clear need for more detailed statistical information about

financial flows from private households and corporations to low-tax

and no-tax jurisdictions. Action should also be taken at an international

level to ensure the ability to identify the ultimate beneficial

owner of assets held in corporate entities such as trusts and foundations,

for example by imposing on the agents that administer these entities

obligations similar to those imposed on banks to counter money-laundering.

For this reason, the Assembly should also support the G20’s call

on the Global Forum to draw on the work of the Financial Action

Task Force (FATF) on beneficial ownership.

90. Even if such measures can be agreed and implemented, however,

they are unlikely to be effective unless governments agree on a

“Big Bang” approach, whereby tax havens are required to sign treaties

with all countries, in place of the current incremental policy.

This could also be readily accomplished by requiring tax havens

to sign the multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance

in Tax Matters. The Big Bang approach should be supported by the

threat of restrictions on financial transactions with non-compliant jurisdictions,

in order to prevent the otherwise inevitable prospect of leakage

of funds to locations that continue to offer facilities enabling

tax evasion. International co-operation at the level of the G20

is needed to achieve such an objective, but the OECD has a key role

to play in preparing the ground for such co-operation. The enlarged

Assembly should urge the OECD to work with its member countries

to significantly step up the pressure for action on all these fronts.

The OECD should be the driving force for a new, comprehensive campaign

of action against tax havens.