1. Introduction

1. Having tabled a motion on the right to Internet access

(

Doc. 12985), I was appointed rapporteur on this subject by the

Committee on Culture, Science, Education and Media of the Parliamentary

Assembly on 2 October 2012. On 30 November 2012, the Assembly’s

Bureau mandated me also to take into account the motion for the

promotion of media content on the Internet (

Doc. 13014).

2. In close co-operation with me, Ms Riikka Koulu from the University

of Helsinki prepared a substantial background report for the Committee

on Culture, Science, Education and Media (document AS/Cult (2012) 08) and

presented it to the committee in Paris on 11 March 2013. This report

serves as the substantial part of this explanatory memorandum.

3. I am particularly grateful to Ms Koulu, as well as to Professor

Wolfgang Schulz from the Hans Bredow Institute in Hamburg and Mr

Abel Caine, Programme specialist from the Communication and Information Sector

at UNESCO, all of whom participated in an exchange of views with

the committee on that occasion.

4. Speaking on behalf of the Finnish delegation to the Council

of Europe’s Conference of Ministers responsible for media and information

society in Belgrade on 7 November 2013, I reported on this work

and had an exchange of views with other participants in the ministerial

session I on “Access to the Internet and fundamental rights”.

5. Having put elements for a draft resolution for public consultation

on the Facebook website

in November 2013, I received little

feedback. This may be due to the fact that Facebook is a social

platform for more spontaneous discussions. However, it is interesting

to note that Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and CEO of Facebook, has

launched an initiative for universal access to the Internet.

I also sent the draft elements

for a resolution to various stakeholders, including the European

Internet Service Providers Association (Brussels), the International

Chamber of Commerce (Paris), Facebook and ARTICLE 19 (London). I

am very grateful for the constructive reply by ARTICLE 19.

2. The relevance

of Internet access for individuals and society

2.1. Growing importance

of Internet

6. In the 21st century, Internet has become a central

part of everyday life for its 2.4 billion users worldwide.

Defining Internet comprehensively

requires understanding its social significance and possibilities,

but as a working technical definition Internet can be described

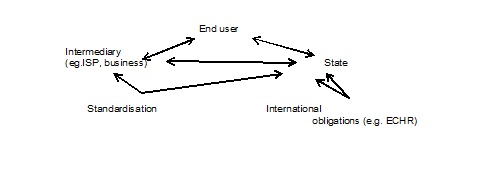

as networks of computers and servers linked together by globally

standardised protocols enabling high-level data transfer between

the computers.

Wide-spread consensus

exists that Internet is a unique medium in comparison to other forms

of mass media.

7. Internet access has transformed from a communication forum

accessible only to a selected few into a mainstream medium for managing

banking, health care, work and administrative issues. What these

changes specifically entail is difficult to decipher as the transition

into information society is still work in progress in many European

countries. The level and pace of technological progress varies substantially

from country to country. In the forerunner countries, such as Scandinavia,

almost all households have Internet access, whereas in other European

countries the broadband penetration rate does not extend to the

same level. There is a digital divide between different geographic

areas and countries. The stage of development affects the ways technology impacts

society and Scandinavian countries and other countries of high technology

therefore reflect possible future progress in other countries as

well.

8. However, it is evident already at this point that the adoption

of information and communication technology (ICT) has permanent

and far-reaching consequences on society and that this development

cannot be reversed. The historical change brought about by the emergence

of new media and computer networks cannot be reduced only to technical

terms, as such an approach would disregard the societal changes. Individuals

depend increasingly on computer networks such as Internet. Most

notably, the role of Internet in everyday life connects with digitisation

of data which enables the relay of high volumes of data with no

(or very low) costs. This creates the possibility for individuals

and other actors to participate in context production at the same

time as consumers and providers (user generated content, interactivity).

This

transformation of mass media also carries vast economic importance.

9. The range of public and private “e-services” (electronic services

utilising ICT) is proliferating rapidly and, in some cases, even

replacing the existing, traditional services. The transformative

power of Internet is based on the low threshold, real time possibility

to distribute data from one-to-many regardless of national borders and

without central control. Online applications have become intertwined

with traditional everyday practices. Such applications include,

among others, online banking (managing bank transactions or checking

account information online),

![(7)

Online

banking is one of the most common usages of Internet connection.

For example, in the European Union countries 38% of individuals

have used Internet banking in the last three months for transactions

or for account information. See: <a href='http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do?tab=table&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=tin00099'>http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do?tab=table&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=tin00099</a> [22.1.2013].](/nw/images/icon_footnoteCall.png)

e-commerce (sale and

trade of material or immaterial goods online, consumer protection online),

![(8)

According to Eurostat,

34% of individuals in the European Union have made purchases on

the Internet in the last three months. See: <a href='http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=isoc_ec_ibuy&lang=en'>http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=isoc_ec_ibuy&lang=en</a> [22.1.2013]. The Eurostat survey demonstrates that corresponding

percentage among enterprises is substantively less, only 16%. See: <a href='http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do'>http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do</a> [22.1.2013].](/nw/images/icon_footnoteCall.png)

and e-work (remote

work where employees work without commuting to the work place with

the help of ICT). Of growing importance is also e-health, technology-supported

public or private health care, which, in the wide sense, includes

patient data management as well as online consultation with health-care

personnel, and online applications designed for rehabilitative health

care.

10. In addition to this, governmental organisations and public

services are increasingly going online. E-government refers to interaction

between government officials and citizens or enterprises conducted

online.

![(9)

According

to Eurostat, 41% of individuals in the European Union have had interaction

with public officials online during the last 12 months. The study

shows that the equivalent percentage in Norway was 78% and in Iceland

84% in 2011. See: <a href='http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=isoc_bdek_ps&lang=en'>http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=isoc_bdek_ps&lang=en</a> [22.1.2013].](/nw/images/icon_footnoteCall.png)

One aspect of e-government

is government action to promote e-services such as electronic communication between

individuals and courts (e-justice), applying for social and other

benefits online, and participation in governance through computer

networks. One of the most far-reaching e-government applications

is electronic voting piloted in Finland.

Another perspective of the relevance

of Internet access to democratic society are the new forms of participation

in policy making (e-participation). In addition to grass-root level

Internet activism of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), also

government-encouraged methods of participation are increasingly

brought to public attention via the Internet. In Finland, the Ministry

of Justice has enabled participation by launching an online service

for citizens’ initiatives. Through this service, individuals can

have their bill or proposal to start a bill drafting process considered

by the parliament.

Such services and channels of influence

can increase civic activity, participation and voice in local decision-making

and thus strengthen democratic civic society (e-democracy). However,

lack of equality in Internet access can cause exclusion of some

groups from this development.

11. As is evident from such examples, Internet has become a crucial

commodity not only for facilitating commerce or communication but

for using basic public and private services such as banking, health-care

or welfare services. In addition to such functions, Internet has

already become a method for participation and offers possibilities

to increase civic influence in a democratic society. The indispensable

role Internet has in modern society is further emphasised as both

governments

![(12)

In

Finland, for example, the use of e-services in relation to government

officials and public courts is promoted through legislation. See:

Act on Electronic Services and Communication in the Public Sector

(13/2003) [Laki sähköisestä asioinnista viranomaistoiminnassa],

unofficial English translation available at: <a href='http://finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/2003/en20030013.pdf'>http://finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/2003/en20030013.pdf</a>.](/nw/images/icon_footnoteCall.png)

and international actors such as

the European Union

promote the use of online services.

12. It is noteworthy that Internet as such is neither good nor

bad, but instead can be used for contradictory ends. Internet’s

nature as an interactive medium of communication does not directly

mean that Internet should be regarded one-sidedly and merely as

an enabler of rights or as a potential venue for violations of rights. Internet

has the potential to significantly increase participation and to

facilitate freedom of expression. However, at the same time, these

rights can be misused online and Internet can be turned into an

instrument for censorship, surveillance or cybercrime. In comparison

with traditional media, the advantages for civic society and anxieties

of misuse can both be seen to be more considerable on the Internet,

due to the interactivity. In conclusion, Internet infrastructure per se cannot be declared as pro or contra human

rights, but should be seen as a neutral medium which can be used

for conflicting purposes.

2.2. Acknowledging Internet

access as a right

13. At present, the prevailing opinion is that access

to Internet should be recognised as a fundamental right. In the

following section, this consensus will be presented in more detail

by emphasising national broadband policies, the European Union agenda,

national case law and public opinion. The consensus is starting

to form through actions and discussions of several governments,

international actors such as the United Nations, the European Union,

the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE),

the Committee of Ministers of the

Council of Europe

, the International Telecommunications

Union (ITU), as well as of Internet stakeholders and private individuals.

These actions include recognising the importance of Internet for

freedom of expression,

promoting the public service value

of Internet and adopting broadband policies to this end, and the

gradual emergence of case law from the national and international

courts.

14. Criticism is nevertheless voiced about regarding Internet

access as a human right. One of the most cogent reviews has been

presented by Vint Cerf, who is often presented as one of the creators

of Internet. Cerf stated in a

New York

Times opinion that “Technology is an enabler of rights,

not a right itself”. Cerf noted that Internet is an important means

to an end, creating new possibilities for people to exercise their

human rights. However, according to Cerf, acknowledging access to

Internet as a universal service comes close to regarding access

as a civic right.

As a response to Cerf’s opinion,

Amnesty International USA has noted that Cerf’s view of human rights

is particularly narrow and tantamount to contesting physical access

to a town square as a human right without understanding that such

access is inseparable from the right of association and expression.

15. In any case, these two arguments should be conceptually separated

from one another: Internet access as a human right per se on the one hand and Internet

access as an indispensable enabler of human rights on the other.

Although it can be disputed whether Internet is per se a human right, it is often

recognised that Internet is a crucial tool for exercising human

rights. The latter is also the point of origin in the United Nations Special

Rapporteur’s report discussed below.

16. Because of the central functions and possibilities of Internet,

several countries have acknowledged that access to Internet has

become a focal tool for exercising freedom of speech and opinion

and thus requires protection as a fundamental human right.

As of 2011, national policies for

promoting broadband access had been adopted in more than 100 countries

worldwide.

Also, agencies such as the Broadband

Commission for Digital Development, joint project of the ITU and

the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

(UNESCO), promote broadband policy making.

17. The European Union has recognised access to Internet as a

universal service in Universal Service Directive (2002/22/EC) on

universal service and user’s rights relating to electronic communications

networks and services. The directive obliges member States to ensure

that requests for connection at a fixed location to the public telephone

network are fulfilled. According to Article 4.2, “The connection

provided shall be capable of allowing end-users to make and receive

local, national and international telephone calls, facsimile communications

and data communications, at data rates that are

sufficient to permit functional Internet access, taking

into account prevailing technologies used by the majority of subscribers

and technological feasibility” [emphasis added].

18. The implementation of the directive is subject to judicial

review. The European Commission requested the Court of Justice to

fine Portugal for failing to designate telecom providers as universal

service providers in accordance with the Directive. In its judgment

(case C-154/09) of 7 October 2010, the court declared that the Portuguese

Republic had failed to fulfil its obligations as it had not transposed

the obligations into national law and had failed to ensure their

application in practice. On 24 January 2013, the European Commission requested

the court to impose further fines on Portugal, which had still not

fulfilled all of its obligations.

19. National courts have also started to consider Internet access

as a crucial commodity for daily life. The German Federal Court

of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof) came to this conclusion in its recent

decision (III ZR 98/12) on 24 January 2013, as it granted compensation

to a plaintiff who was disconnected from accessing Internet between

December 2008 and February 2009 due to the service provider’s failure

to provide connectivity. The court ruled that access to Internet

had already become of central importance for individuals as it:

offers access to a wide-range of information globally – replacing

traditional media such as television and print media –, and enables

communication between users. In addition, the court recognised that

Internet is increasingly used for transactions, concluding contracts

and fulfilling obligations of public law.

20. The public is also starting to acknowledge access to Internet

as a right. As a global survey conducted for the BBC World Service

in 2009 and 2010 demonstrates, a vast majority of adults (79%) in

the 26 countries participating in the poll stated that access to

Internet should be a fundamental right. It is noteworthy that also 71%

of non-Internet users considered that they should have the right

to access Internet while the corresponding percentage among Internet-users

was 87%. For Internet-users, the most valued uses of Internet included

finding information (47%), interacting and communicating with other

people (32%), and a source of entertainment (12%).

As such studies reflect public

opinion, the information is also valuable for policy making.

21. Although several stakeholders have agreed that access to Internet

is to be considered as a human right, it is still unclear how this

access is defined and what it involves. Most statements, travaux préparatoires for universal

services acts and other recommendations emphasise Internet as an

enabler of freedom of expression. This implies that there is an

obligation to provide free access to information (access to content)

and communication without censorship, to participation and social

activism and to the use of online services and e-commerce. However,

many issues have not yet been discussed at all. Depending on the

interpretation regarding definition of access, it could also be

argued that this right includes the right to host a server or use such

access for equivalent purposes.

22. Due to its unique nature, it is widely accepted that access

to Internet cannot be directly compared to traditional forms of

mass media with an ex analogia interpretation.

Especially applications such as social media elude comparison. Regardless

of this, analogy to traditional media could be useful for some uses

of computer networks, for example e-mail. As questions concerning

e-mail (such as privacy of correspondence) are notably similar to

those already examined in relation to traditional mail, discarding

analogy interpretation in its entirety, without case-by-case examination,

is not necessary reasonable.

3. Technical aspects

of Internet access

3.1. Infrastructure

23. As the pace of technology development is especially

rapid, opinions on the right to Internet access rarely take a stand

on the technical realisation of this right. Instead, they leave

it to be decided by the Internet service provider (ISPs) and national

policy makers, according to the available technical possibilities.

In brief, Internet access requires a telecommunications network,

last-mile telecommunication (the access point at the user’s home,

infrastructure), and end equipment (computer, hardware) for accessing

the network. Software is used to administer the hardware. The infrastructure

and last-mile telecommunication can be organised in several ways.

24. It is evident that the available technical options have an

impact on legal regulation as well. However, the relationship between

technology and regulation is two-way, as standardisation determines

the development of technology. The prevailing opinion is that technology

neutrality should be adopted as a starting point in future legislation.

However, some standpoints have been taken, for example by European

Union policy setting and national broadband strategies, all promoting

high-speed broadband bandwidth. Such bandwidth can be achieved by

several technical alternatives or combination of them, wireless

transmitters or wires. For example, in the United Kingdom, broadband

strategy has adopted a mix of technologies combining fixed, wireless

and satellite connections.

25. At this point of development, access to Internet requires

the use of data terminal equipment such as a computer or mobile

telephone. Although Internet access is declared a universal service,

it does not follow from there that the State should provide such

access for free without costs of ISPs or procurement of the end equipment.

However, it has to be taken into consideration that the costs of

Internet access might in themselves be prohibitive for some individuals,

increasing the digital divide in developed countries as well. Consideration should

be given to whether the State should take positive action in order

to provide access through public WLAN (wireless local area network)

connections and public access points through library or other such

public services to those individuals and households that cannot

afford the costs.

26. In its European Broadband Communication, the European Commission

set the objective that by 2020, all Europeans should have access

to Internet of above 30 megabits per second (Mbit/s) and 50% or

more of European households have subscriptions above 100 Mbit/s.

The Commission highlights that optical fibre technology (fibre to

the home, FTTH) should be preferred for last-mile telecommunications

as it can utilise the existing copper network. Optical fibre has

been described as future-proof for the relayed bandwidth is limited mostly

by the end equipment. However, the use of mobile technology for

the last mile communication is constantly on the rise. The Commission

states that also next-generation terrestrial wireless services as

well as satellite connection, if further development is undertaken,

will be able to reach the target bandwidth. The European Union objective

is very ambitious and calls for active member State action. However,

the halfway objective adopted as a part of the Finnish Broadband

2015 Strategy, securing the minimum bandwidth of 1 Mbit/s, is sufficient

for accessing most Internet services effectively.

27. Funding the development of Internet infrastructure is one

of the issues related to the future of Internet. Although the European

Union, for example, provides targeted infrastructure funding at

European level, investments are made and Internet traffic hubs are

run most often by private businesses, ISPs etc. This further highlights

the importance of adopting the multi-stakeholder model in governance

issues.

28. One example of the importance of infrastructure is the role

of Internet Exchange Points (IXPs). They enable Internet traffic

from one operator’s autonomous network to that of another (direct

interconnection) without third-party networks or peering. This makes

data transfer cheaper and faster and more fault-tolerant. IXPs are

governed by non-profit Internet Exchange Point Associations (IXPA)

whose member corporations are national and international ISPs. On

an international level, there are four regional IXPAs for Europe,

Africa, Asia Pacific and Latin America.

3.2. Software

29. It is evident that effective exercise of access to

Internet requires computer literacy in addition to the absence of

restrictions on access and denomination of universal service providers

(USPs). Lack of adequate computer skills prevents certain groups

from taking full advantage of the possibilities of Internet. A “digital divide”

exists between different geographic areas (different continents,

rural/urban areas) – where the term refers to the missing possibilities

of the necessary infrastructure – but also in developed areas where differences

between individual skills, economic abilities, physical disabilities

or age can translate into de facto obstacles

for utilising the potential of Internet services.

30. In the development of software, the role of intermediaries

(such as Internet businesses) is central as adopted software architecture

often directs future user behaviour. For several groups, such as

the elderly and immigrants, the learning curve for using Internet

services has to be set as low as possible. In Finland, for example,

a small eHealth business (Pieni piiri) is offering a collaborative

Internet experience as a method of engaging the elderly in interactive

Internet services, which, in its turn, gives them the necessary

know-how to access other services as well.

31. The future prospects of software development are almost impossible

to predict. However, it is evident that the significance of software

will increase in the future and data will be increasingly stored

on cloud services. Already individual apps have started to gain

ground on traditional Internet browsers and the importance of social

media is highlighted. As a part of this, use of Internet access

will probably become both more tailored and more community-oriented.

Due to insufficient data transfer capacity, earlier software applications

have been text-based, but as the broadband bandwidth becomes customary,

there will be no obstacles to relaying audiovisual information,

which will affect future software infrastructures.

4. Legal norms applicable

to Internet access and use

32. There are several sets of rules that affect the evaluation

of Internet access and its use. Most of these norms are founded

by binding international instruments. However, such instruments

have been enacted for very different purposes. It is necessary to

differentiate the norms that regulate the human rights perspective

of Internet access from the norms regulating the technical aspects:

how such access is used, what technical standards are in place for

the necessary interoperability and how restrictions on content are

imposed. The technical solutions nevertheless affect the recognition

and interpretation of the human rights perspective as they substantially

affect the way Internet is developed and used. In addition to international

regulation of human rights and technical standards, there are also

the national legislations which might impose specific technical requirements

or rights for citizens. All in all, the legal norms applicable to

Internet are diverse and fragmented between different fields.

4.1. United Nations

33. As stated above, the freedom of opinion and expression

is one of the central human rights connected with the use of the

Internet. Freedom of expression is protected under Article 19 of

the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 16 December 1966. The

treaty has 74 signatories and 167 Parties and its implementation

is monitored by Human Rights Committee through a reporting procedure,

the examination of individual complaints and the publication of

general comments on the interpretation of the ICCPR. Article 19

of the ICCPR decrees freedom of opinion and expression to include

first, the right to hold opinions, and second, the right to seek,

receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds through any

media. According to Article 19, this freedom carries with it special duties

and responsibilities and therefore it may be subjected to a restriction

regulated by law and necessary for the respect of rights or reputations

of others or for the protection of national security, public order

(ordre public) or public health or morals.

34. In 2011, the Human Rights Committee has addressed new media

in its General Comment No. 34, stating that:

“States parties should take account of the extent to which

developments in information and communication technologies, such

as internet and mobile based electronic information dissemination systems,

have substantially changed communication practices around the world.

There is now a global network for exchanging ideas and opinions

that does not necessarily rely on the traditional mass media intermediaries.

States parties should take all necessary steps to foster the independence

of these new media and to ensure access of individuals thereto.”

35. An important step towards recognising access to Internet was

taken when the United Nations Special Rapporteur on promotion and

protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, Frank

La Rue, submitted his report to the Human Rights Council on 16 May

2011. In his report, the Special Rapporteur concluded that access

to Internet was a key means of exercising freedom of opinion and

expression. He states that:

“The

right to freedom of expression is as much a fundamental right on

its own accord as it is an ‘enabler’ of other rights, including

economic, social and cultural rights, such as the right to education

and the right to take part in cultural right and to enjoy the benefits

of scientific progress and its applications, as well as civil and

political rights, such as the rights to freedom of association and

assembly. Thus, by acting as a catalyst for individuals to exercise

their right to freedom of opinion and expression, the Internet also facilitates

the realization of a range of other human rights.”

36. Most of the observations and recommendations presented by

the Special Rapporteur are pertinent in the European context as

well. Especially important points of the United Nations report are:

first, the critical attitude adopted towards all restrictions on

content; second, its demands for applying cumulative criteria to

all restrictions; and third, the insistence on transparency. The

Special Rapporteur demands that restrictions on Internet content

are evaluated by an independent body using the three-part, cumulative

restriction criteria regulated in Article 19.3 of the ICCPR (regulated

by law, for specific purposes, necessary). Sufficient legal remedies

should be made available. He calls for more transparency in situations

where a State uses blocking or filtering mechanisms and points out

that legitimate online expression is in practice criminalised by

applying laws on defamation, national security and terrorism which,

in fact, aim to censor content. The Special Rapporteur calls for

State action to ensure access to Internet at all times and considers

disconnection of users from Internet as interference with constitutional

rights, regardless of the ground for such action. This includes suspension

based on copyright infringements, which suspensions he regards as

disproportionate and, as such, a violation of freedom of expression.

This is a remarkably strong statement, which I will discuss below.

4.2. Council of Europe

37. Freedom of expression is provided for in Article

10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, drafted by the Council

of Europe and opened for signature on 4 November 1950. In total,

47 countries have ratified the treaty. The Convention defines freedom

of expression in a similar manner as the ICCPR. According to Article

10 of the Convention, freedom of expression includes: i) freedom

to hold opinions; and ii) freedom to receive and impart information

and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless

of frontiers. Freedom of expression may be subject to such formalities,

conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and

are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national

security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention

of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for

the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing

the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining

the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.

38. The European Court of Human Rights (“the Court”) has not yet

directly evaluated access to Internet from a human rights perspective

and, therefore, exact rules for interpretation cannot be found in

the Court’s case law. However, pending cases concern refusal of

prison authorities to give a convicted prisoner access to Internet

(alleged violation of Article 10, Jankovskis

v. Lithuania, Application No. 21575/08) and a news portal’s liability

for defamatory comments posted on it (alleged violation of Article

10, Delfi As v. Estonia, Application No.

64569/09). Tangential cases have also already been evaluated by

the Court.

39. In the Editorial Board of Pravoye

Delo and Shtekel v. Ukraine case, the Court unanimously

ruled that there had been a violation of Article 10 of the Convention,

as the Ukrainian law did not provide safeguards for journalists

publishing materials obtained from the Internet, although immunity

from civil liability was granted to journalists using verbatim citations

published in the press. The applicants, the editorial board and

editor-in-chief of a newspaper, had published an anonymous letter

downloaded from a website. Although the newspaper had provided the

reference to the Internet source and a disclaimer stating that the

information was not necessarily correct, the national court found

the applicants liable on the basis of defamation. The European Court

of Human Rights declared that such liability for reproduction of

Internet material violated the journalists’ freedom of expression.

40. In K.U. v. Finland,

the Court declared that there had been a violation of Article 8

(the right to respect for private and family life), as the Finnish

legislature did not provide a framework for reconciling the confidentiality of

Internet services and the protection of others. The Court pointed

out that, although it is understandable that regulation in information

society falls behind due to the pace of technology development,

the Finnish legislator should have been able to provide for the

necessary safeguards in 1999 when the initial incident had taken place.

Although such protection was subsequently created, the national

legislation had failed to provide sufficient protection for the

applicant, whose right to privacy had been violated.

41. In Ahmed Yildirim v. Turkey,

the Court ruled that there had been a violation of freedom of expression

as a national court had ordered the blocking of access to Google

Sites, which hosted a website whose owner had been accused of defamation

of Atatürk. Based on the court decision, access to all other sites

hosted by Google Sites was blocked as well.

42. In Ashby Donald and Others v. France,

the Court ruled that there had been a violation of the freedom of expression

as the national court had convicted three fashion photographers

for copyright infringement. The national court had found that there

had been an infringement as two of the defendants published on their website

photos taken at fashion shows by the third defendant without the

consent of the fashion shows concerned.

43. The Council of Europe has also adopted other treaties that

are relevant to access to Internet. The Convention on Cybercrime

(ETS No. 185) and the Convention on Data Protection (ETS No. 108)

are important treaties regulating the use of Internet access and

providing for protection of Internet users. The Convention on Cybercrime,

which came into force in 2004, is the only international and binding

instrument on cybercrime. The Treaty provides States with guidelines

for the development of legislation against organised crime such

as terrorism, paedophile networks, child pornography and computer

frauds.

44. Adopted in 1981, the Convention on Data Protection is the

only binding legal instrument concerning privacy and it sets minimum

standards for the level of protection and harmonisation. Due to

the growing concern about surveillance and profiling on the Internet

and other data protection issues, an updated draft of the convention

will be examined by an intergovernmental Council of Europe committee

in 2014 before being submitted to the Committee of Ministers.

4.3. Contextuality of

relevant human rights in relation to Internet access

45. The prevailing opinion is that access to the Internet

is particularly central for freedom of expression and should be

provided for as a civic and political right. This doctrinal choice

has been made in Frank La Rue’s report (see paragraph 31) and in

several other documents. However, access to Internet and use of

political freedoms online should be separated from the question

of how this access is guaranteed. The widely adopted practice is

that telecom providers are designated as universal service providers

and obligated to provide sufficient Internet access. The right to

enter into a contract with a telecom provider in order to receive

the universal service has to be evaluated separately from State

obligations. The following graph clarifies the relationships and

obligations between the different parties.

46. Incongruity between traditional media and the Internet

renders ex analogia useless

as an interpretation method. This also affects the question of which

human right applies to the Internet. Although freedom of expression

is the human right most often connected with access to Internet,

other human rights might become relevant depending on the context

and interpretative issues. In different contexts, access to Internet

could be evaluated through other rights as well, for example the

right to education (e.g. use of licenced educational material) or

as a part of fair trial (e.g. in online dispute resolutions or technology-enhanced

trials). A growing number of national courts are relying on Internet

access in their case management and expect Internet capabilities

from the parties and their representatives as well (e.g. Finnish

legal aid appliances, lower court fees for e-claims, etc.), raising

the questions of due process and equality of arms. The implications

of technology implementation in dispute resolution are one of the

new legal issues arising from Internet and further research on the

matter is therefore necessary.

47. It is noteworthy that the context defines the relevant human

rights and this might have implications on the obligations placed

to the parties involved, on the contracting States on the one hand

and on Internet intermediaries on the other. This is to say that,

according to the human rights doctrine, civil and political rights entail

obligations going further than economic, social and cultural rights.

4.4. Rights of Internet

users

48. The rights of Internet users should be provided for

and the same level of legal protection guaranteed online as offline.

To this end, the European Union has published the Code of EU Online

Rights as a part of the Digital Agenda for Europe. The code includes

rights and principles i) applicable to access and use of online services,

ii) applicable to the purchase of goods and services online and

iii) providing protection in case of conflict.

49. As the United Nations Special Rapporteur states, the responsibility

of intermediaries in securing freedom of expression is important

and thus, they should “only implement restrictions on these rights

[freedom of expression] after judicial intervention; be transparent

to the user involved about measures taken, and where applicable

to the wider public; provide, if possible, forewarning to users

before the implementation of restrictive measures; and minimise

the impact of restrictions strictly to the content involved”. The

prevailing opinion concerning the rights of users is that, in addition

to providing the necessary safeguards through regulation, also effective

legal remedies must be guaranteed. These effective remedies include

appeal procedures provided by the intermediary as well as judicial

review.

4.5. Standardisation

50. The regulation of Internet is not only a legal and

political issue, but a technical one as well. Securing interoperability

also in the future is elemental for the future use of the Internet;

this is achieved by continuous standardisation work. The United

Nations International Telecommunication Union (ITU) strives for standardisation

of ICT infrastructure to overcome technical barriers and to ensure

accessibility, seamless global communication and interoperability

between operators and technical networks. As of 2011, ITU had already

given over 3 000 recommendations, including standardisation of broadband

access, fibre optic transport, cabling, PONs (passive optical networks)

and fixed-mobile convergence. Further standardisation work by the

ITU is crucial for overall network operation.

51. On 14 December 2012, the ITU convened the World Conference on International

Telecommunications (WCIT-12) in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. The

conference reviewed the International Communication Regulations

(ITRs) and a binding treaty for the facilitation of interoperability

was approved and presented for signature in the final acts of the

WCIT. The treaty: i) establishes general principles relating to

the provision and operation of international telecoms; ii) aims

to facilitate global interconnection and interoperability; iii)

promotes harmonious development and efficient operation of technical

facilities; and iv) promotes efficiency, usefulness, and availability

of international telecommunication services.

52. These technical issues also have important human rights aspects.

A key point discussed at WCIT was the future governance of Internet.

The participants discussed whether ITU should take a more decisive

role in regulating Internet by introducing a regulatory framework

for controlling it. Although no such mandate was given to ITU in

the final acts, a non-binding resolution was adopted in the appendix.

This created controversy as some critics considered that it would

enable the ITU to control Internet content later on and thus disturb

the free flow of information. Because of this, more than half of

ITU member States did not sign the treaty, among them all European

Union member States and the United States. On 14 December 2012,

the European Commission published a memorandum stating that the

European Union member States remained 100% committed to open Internet

in the future. According to the Commission, the final acts risked

threatening the future of the open Internet and Internet freedoms.

53. However, the ITU has recognised the right to communications

as a human right already based on the earlier ITRs.

The final acts accepted in Melbourne

in 1988 (WATTC-88) have been approved by 190 countries including

the European Union member States and the United States. Article

3.4 of the final acts states that “subject to national law, any

user, by having access to the international network established

by an administration, has the right to send traffic. A satisfactory

quality of service should be maintained to the greatest extent practicable,

corresponding to relevant CCITT Recommendations”.

54. The European Commission has identified lack of interoperability

as one of the most significant obstacles to exploiting technology.

In the Digital Agenda for Europe, the Commission has listed actions

for promoting standard setting in the European Union. These actions

include the promotion of standard-setting rules, guidance on standardisation

and the adoption of a European Interoperability Strategy and Framework

(EIF). The EIF is a collection of recommendations that define how

administrations, businesses and citizens communicate with each other

regardless of member State borders.

55. The ministerial declarations adopted in Malmö and Granada

commit to creating a single digital market in the European Union.

To this end, public administrations should promote open standard

and interoperability between national and European frameworks and

develop more efficient interoperable public services. The European

Commission has also harmonised the use of the 3 400-3 800 MHz frequency

band for terrestrial systems capable of providing electronic communications

services in the Community (2008/411/EC). It is probable that the

importance of European Union standardisation will increase in the

future.

4.6. Governance of Internet

domain names

56. Governance and control over Internet domain names

is carried out by the private non-profit organisation The Internet

Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) based in the

United States. ICANN organises the distribution of unique Internet

Protocol (IP) address spaces to the five regional Internet registries

which, in their

turn, manage allocation and registration for specific geographic

regions. ICANN protects the stability and operability of global

Internet by co-ordinating the domain name system. In order to resolve

domain name conflicts, ICANN has established its own dispute resolution

model called the Uniform Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) in co-operation

with the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). Because,

in the end, ICANN is a private organisation entrusted with responsibilities

of public interest, it has been criticised for lack of adequate

accountability mechanisms.

4.7. Broader obligations

for the State

57. The human rights perspective of Internet access creates

obligations for the States that can be carried out in several ways.

As the national broadband policies demonstrate, promotion of broadband

as a necessary commodity is often depicted as a practical way of

implementing the right to Internet access. For example, on 4 December

2008, the Finnish Government launched the “Broadband 2015 project”.

The objective of the Broadband project is that in 2015, more than

99% of the population are no further than two kilometres from a 100 Mbit/s

fibre-optic or cable network. This enables the consumers to obtain

Internet connection from telecom operators, at their own expense.

![(30)

Resolution of the Finnish

Government on national strategy for improvement of the infrastructure

of the information society (732/2009) [Valtioneuvoston päätös kansallisesta

toimintasuunnitelmasta tietoyhteiskunnan infrastruktuurin parantamiseksi],

4 December 2008, pp. 1-2.](/nw/images/icon_footnoteCall.png)

58. All individuals and businesses in Finland are considered to

have the right to high-speed Internet access in their place of residence.

Amendment of section 60.c of the Communications Market Act (393/2003),

which came into force on 1 July 2009, enacts that certain telecom

operators have the obligation to provide the public with an appropriate

Internet access, regardless of their place of residence, but taking

into consideration the connection speed available to the majority,

technical realisation and costs. Based on the amendment, the Finnish

Communications Regulatory Authority designated 26 telecom operators

as universal service providers (USPs) of Internet access. These

USPs have the obligation to offer Internet access in their specific

geographic areas of operation. The decision came into force on 1

July 2010. The Finnish legislator has also decreed the speed requirement

for an appropriate access. As the Finnish Communications Regulatory

states, technology requirements and level of appropriate technology

might vary depending on the development level, which is one of the

reasons why the provisional speed requirement of broadband speed

(1 Mbit/s) for incoming traffic is regulated by a decree of Ministry

of Traffic and Communications.

The Finnish broadband model gives

other countries valuable information on the practical issues of

implementing broadband strategies.

59. Such regulation on USPs creates obligations for Internet stakeholders.

In Finland, the governmental resolution on the Broadband Project

starts out from technology neutrality and leaves the decisions concerning the

technology used to the USPs’ discretion.

4.8. Governance of Internet

and multi-stakeholder model

60. The governance of Internet involves multiple stakeholders,

such as civil society, private sector businesses, governments and

NGOs, which

de facto co-operate

in policy-making processes. Especially the role of intermediaries

in administering content has evolved significantly and private businesses

have responsibility regarding the rights of Internet users. Consequently,

all stakeholders should be engaged in future policy-making procedures.

The prevailing opinion is that, although the States have the primary

obligations to provide a regulatory framework for Internet, other

Internet stakeholders also have an important role in future policy-making

and governance of Internet.

Co-operation and dialogue between

different stakeholders enables openness, transparency and accountability

of adopted policies and enables the responsibilities and roles of

different stakeholders to be taken into account.

61. Companies in the ICT sector are encouraged to partake in multi-stakeholder

models such as the Global Network Initiative, an NGO devoted to

promoting human rights and privacy and preventing censorship on Internet.

This multi-stakeholder initiative was founded in 2008 by the important

gatekeeper corporations Google, Microsoft and Yahoo!. The growing

importance of the multi-stakeholder model as a governance structure

influences future norm-giving and policy-forming.

5. Prominent cases

62. Widely discussed cases related to the right to Internet

access concern protection of intellectual property rights on the

Internet, boycott of services, filtering by the State, censorship,

surveillance and other means of limiting access to Internet or access

to certain content.

63. Sufficient protection of intellectual property rights, particularly

copyright is central to the further development of Internet. However,

the means of providing such protection must not infringe the fundamental rights

provided for in the European Convention on Human Rights and other

human rights instruments. French law aiming at protection of copyright,

namely the HADOPI law has created a lot of controversy. The law, adopted

in 2009, is based on a three-strikes-penalty model, where a government

agency (HADOPI) invokes the policy in repeated copyright infringement

situations at the request of the copyright holder. In the first

stage, an e-mail message is sent to the Internet access subscriber

(based on the IP address) inviting him or her to install a filter

to the connection. If in the following six months the infringement

is repeated, HADOPI invokes the second step of the policy and a

registered letter is sent to the subscriber. If in the following

12 months, the offence is repeated, the third step is invoked and

the Internet service provider is asked to suspend the subscriber’s

Internet connection for a period of between 2 and 12 months while

the subscriber’s obligation to pay for it continues. Judicial review

before a court is allowed in the third stage.

64. The HADOPI law has provoked a lot of debate and the adopted

three strikes policy is often seen as being a penalty in its nature.

This is problematic as the policy is invoked by an administrative

authority instead of an independent court. Considerable doubt has

been expressed as to how due process, separation of powers and presumption

of innocence are safeguarded under the HADOPI system.

It

has also been claimed that the suspension of Internet access by

an ISP is a violation of fundamental rights. As stated above, the

United Nations Special Rapporteur always regards such suspension

based on IPR protection as a violation of freedom of expression.

Likewise, the OSCE report on freedom of expression on the Internet

declares that countries should refrain from adopting multiple-strike

policies as they are incompatible with the right to information. Revision

of the HADOPI law is under way and the provisions on cutting Internet

access will be removed.

In addition, the European Commission

has declared that in 2014 the review of the European Union framework

for copyright will be completed and, after this, it will be decided

whether legislative reforms are needed.

65. The responsibility of Internet intermediaries is further emphasised

in cases of service boycotts. In these cases, private businesses

operating central services on the Internet decide to ban certain

content from their search results or prevent certain groups from

using their services. An example of such a boycott is the contentious

conflict between Google News and French newspapers originating from

the French print media’s demand that the French Government enact

a law (Lex Google) obliging the search engine to pay for linking their

web pages. Essentially, such demands are based on claims that Google

News receives advertisement revenue belonging to the print media

and on the allegation of Google’s search engine bias as opposed

to the corporation’s supposed net neutrality policy. In response,

Google has threatened to shut out French newspapers from its search

results if such a law is enacted.

No prevailing legal opinion on search

engine bias or the possible copyright infringing nature of news

portals has formed as of yet,

but

it is clear that the enactment of such a law will have an impact

on the future of content regulation on the Internet, as will the private

settlement between the French newspapers and Google News.

On 4 February 2013, the executive chairman,

Eric Schmidt, posted on Google’s business blog that the French President

and Google had reached a private settlement which includes Google

creating a € 60 million Digital Publishing Innovation Fund to support transformative

digital publishing initiatives for French readers. In addition to

this, Google has committed to “help increase their [French publishers]

online revenues using [Google’s] advertising technology”.

66. Another example of service boycotts is provided by PayPal’s

persona non grata policy, which has received widespread criticism.

PayPal is a global corporation providing a service for online money

transfers. There has also been controversy as a result of PayPal

restricting accounts of individual users without prior notice

and shutting down the account of

Wikileaks

while allegedly allowing racist

organisations such as the KKK to keep theirs.

67. Based on the United Nations Special Rapporteur’s report and

other demands for transparency, it is evident that such boycotts

committed by private intermediaries are problematic as users do

not have sufficient remedies against erroneous decisions. Some of

the services provided by private businesses could be considered

to be indispensable to users. However, when creating regulations

to increase transparency, also the freedom of action of the intermediaries

should be taken into consideration. This is an issue related to

the roles of intermediaries, States and end users.

68. As several States attempt to impose regulations on Internet

or filter content, the question of censorship arises. For example,

the Belarus Government has placed filters to control Internet content

through government-owned Beltelecom, which acts as an information

gateway. According to the OpenNet Initiative, a collaborative project

of three research institutions, government involvement in the media

market induces self-censorship for fear of prosecution.

For years, the case of Google China

has been widely discussed in the press as the search engine giant

has fought against the extensive censorship system of China by refusing

to adopt self-censorship on the Chinese market and to filter key

terms such as “human rights” from its search results. According

to the latest news reports, after years of heated debate and partial

compliance with the Chinese Internet censorship laws, Google has

stopped informing its local users that the search results contain

restricted information.

Iran, too, has created filters

for Google’s search engine and e-mail service in order to control

its citizens’ access to content. However, the Iranian Government

plans to impose even more far-reaching censorship by creating a

closed domestic intranet for Iran, thus isolating it from the World

Wide Web.

6. Conclusion

69. In conclusion, it can be argued that Internet access

as such is recognised as a freedom for everyone, which is linked

to the universal human rights of freedom of expression and information

as well as of freedom of peaceful assembly. Other universal human

rights are relevant to determine to what extent Internet access is

protected, such as the rights to protection of private life and

protection of property. In addition, universal service obligations

also qualify Internet access by ensuring universal access, namely

access for everyone at a reasonable price and a defined level of

technical quality, irrespective of location. The above draft resolution contains

the operational conclusions of this report.