1. Introduction

1. The Council of Europe and the European Bank for Reconstruction

and Development (EBRD) signed a co-operation agreement in 1992,

whereby the two institutions agreed to exchange information with

the specific aim of monitoring democratic progress in central and

eastern Europe. In June 2011, the Parliamentary Assembly decided

on certain reforms of its structures and a new division of labour.

2. The new terms of reference of the Committee on Political Affairs

and Democracy state that “the committee shall prepare reports on

the activities of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

(EBRD). For the preparation of the reports and the debates in the

Assembly, the committee maintains relations with the OECD and the

EBRD”.

3. On 22 January 2013, the Assembly held a debate on a report

on the activities of the EBRD in 2010-12, presented by Mr Tuur Elzinga

(Netherlands, UEL), and adopted

Resolution 1913 (2013). On 6 June 2013, the committee appointed me as rapporteur.

4. This report, which is based on a memorandum prepared by Mr

Gabriele Ciminelli, economics researcher at the Tinbergen Institute,

Amsterdam, reviews the activities of the EBRD in 2013 and 2014.

Particular emphasis is dedicated to the economic and political developments

that have characterised the EBRD region of operations in the last

two years and to the recently announced medium-term strategic directions

that will guide the Bank's operations in the second half of the

decade.

5. A short survey of the literature investigating the relationship

between economic development and democracy and an analysis of how

market reform could benefit multiparty democracy in the EBRD transition region

are also provided. Special attention is dedicated to the progress

achieved by the Bank in the new region of the southern and eastern

Mediterranean (SEMED) and the relations of the EBRD with other European Institutions.

6. In preparing this report, the rapporteur held bilateral meetings

with a number of EBRD officials and Board Directors who have provided

her with useful insights into the running and activities of the

Bank. The Sub-Committee on Relations with the OECD and the EBRD

held a meeting at the headquarters of the EBRD in London on 4 February

2014.

2. Background

7. In the year that marks the twenty-fifth anniversary

of the fall of the Iron Curtain, policy makers around the world

are still striving to improve living conditions in the former eastern

bloc. In this context, the EBRD has a unique role to play. Established

in 1991 with the purpose of fostering transition towards an open

market economy, the EBRD is the only financial institution to have

a clear commitment to the principles of multiparty democracy, pluralism

and market economy in its mandate. In fact, the Bank can only carry

out its operations in those countries that are committed to and

apply these principles. As of June 2014, the EBRD was the largest single

investor in its region of operations.

8. The EBRD promotes transition to market economy by making or

co-financing loans, investing in equity capital, and facilitating

access to capital markets of private corporations and State-owned

enterprises operating competitively in the market economy. The extent

of the Bank's engagement with the State sector is however limited

to not more than 40% of the amount of its transactions. To finance

its operations, the EBRD raises funds in the international capital

market. This includes those of its countries of operations, thereby

contributing to the development of the local capital markets.

9. The Bank also provides technical co-operation to its clients,

with the objective of supporting project preparation and implementation.

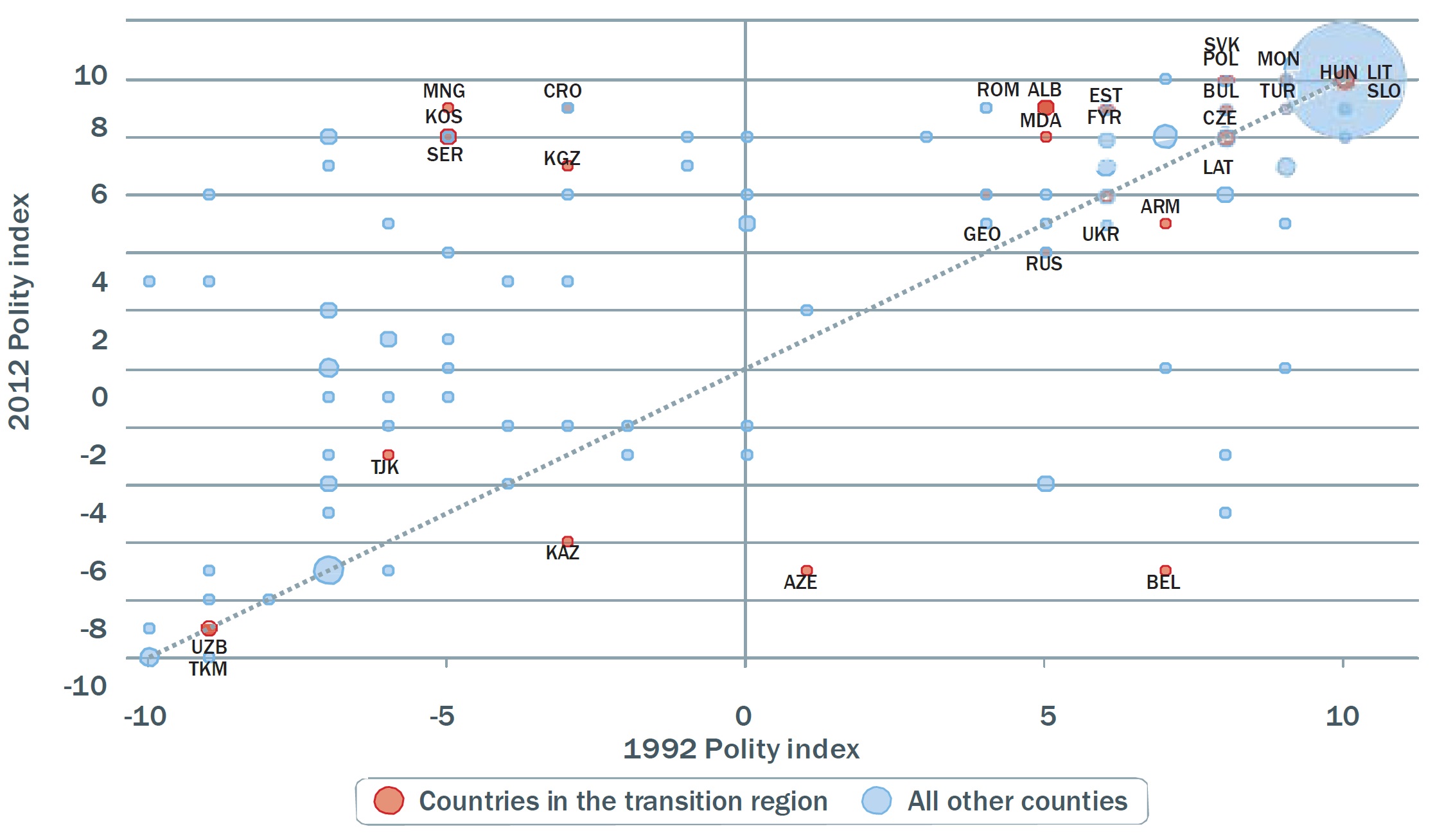

The EBRD constitutes a unique case among development banks insofar

as technical co-operation is paid for via grants financed by donor

partners. Parallel to the investment and technical co-operation

activities, the EBRD also engages in policy dialogue with recipient

countries to foster structural economic reforms. Thanks to the specific

knowledge and expertise acquired during more than twenty years of operations,

the policy advice provided by the Bank has often proved instrumental

in building up the appropriate degree of institutional capacity

that is conducive to the development of an open market economy and

multiparty democracy.

10. Originally, the EBRD region of operations not only comprised

countries of central and eastern Europe and the Balkans, but it

stretched farther east to include the Central Asian republics. Over

time, the EBRD region was gradually broadened, and as of June 2014

it encompassed 35 countries. The operations of the EBRD were first

expanded to Mongolia (2006) and Turkey (2009). Following the historic

changes that occurred in North Africa and the Middle East, in 2011

the Bank's shareholders asked the Bank to extend its geographic

remit to include countries in the southern and eastern Mediterranean

(SEMED) region, notably Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia. Other

SEMED countries have already expressed their desire to join the

Bank.

11. In November 2012, without prejudice to the position of individual

members on the status of Kosovo,*

it was announced that the country

would become a member of the EBRD and recipient country.

During

its Annual Meeting, held in Warsaw on 15 May 2014, EBRD shareholders

agreed on a further expansion of the Bank. Founding member Cyprus

was granted the status of recipient country in order to help the

government to restructure and rebalance the country's economy in

the wake of the financial crisis. The Bank expects its engagement

in Cyprus to be of a temporary nature and plans to carry out its

operations across the whole island, for the benefit of both communities.

12. In order to benefit from EBRD investments, any country first

needs to become a shareholder of the Bank and then receive country

recipient status. This is why, following the intention of the authorities

to seek EBRD investments, Libya's request to become the 67th shareholder

of the Bank has been accepted. The EBRD specified that the decision

to grant recipient country status to Libya would be taken separately,

following a thorough assessment by the Bank of the political, economic

and operational environment in the country, on the basis of Article

1 of the Agreement Establishing the Bank (AEB).

13. The economic and financial challenges that emerged during

the global crisis profoundly affected the prospects of achieving

transition in the EBRD region. Firstly, the financial crisis has

caused the transition region to enter into a prolonged period of

slower growth. This, in turn, has significantly slowed down the

process of convergence to the living standards of western Europe.

Secondly, free markets have often been blamed for the economic malaise.

Consequently, the crisis has dented public support for market-oriented

reforms in a number of countries.

14. The EBRD is well aware that the challenges posed by the financial

crisis and the request for the Bank's expertise and financing coming

from the SEMED region have invariably strengthened its role in the

post-crisis world. During the 2014 Annual Meeting, EBRD shareholders

discussed the new medium-term directions that would guide the Bank's

activities over the following years. Building upon its core competencies

and the important initiatives developed over time, the EBRD aims

to re-energise transition by concentrating its efforts around three

key aims: i) supporting governments in hastening transition through

policy dialogue and the financing of pivotal projects; ii) promoting

economic integration both globally and regionally; and iii) addressing global

common challenges. The medium-term directions provide a starting

point for the discussion over the Bank's Fifth

Capital Resources Review (CRR5), which will cover the

period 2016 to 2020 and is to be approved at the Bank's 2015 Annual

Meeting in Tbilisi.

3. Governance and

structure

15. The EBRD has 66 shareholders. These include all the

member States of the European Union, and two European institutions,

the European Union (represented by the Commission) and the European

Investment Bank (EIB). Furthermore, some developed countries, including

the United States, Japan, South Korea, Canada and Australia, which

are neither European nor countries of operations, are also shareholders

of the Bank. Among the member States of the Council of Europe, only

Andorra, Monaco and San Marino are not shareholders of the Bank.

16. The overall structure of the EBRD is organised along seven

lines, based on shared operational priorities. The division of labour

well embodies the Bank's dual nature of being a publicly owned financial

institution operating according to private sector principles. All

the powers are vested in the Board of Governors, which is composed

of one Governor from each shareholder, usually a civil servant from

the Ministry of Finance or the President of the Central Bank. The

Board of Governors holds a general meeting every year and delegates

most of its powers to the Board of Directors. The Board of Directors

is responsible for the EBRD’s strategic direction and internal evaluation.

The President is elected by the Board of Governors and is the legal

representative of the EBRD. Under the guidance of the Board of Directors,

the President manages the Bank's operations. In carrying out his

tasks, the President is advised by the Executive Committee, which

consists of five Vice-Presidents and other senior management officials,

including the Chief Economist, General Counsel and Secretary General.

17. The meetings of the Board of Directors are usually held every

two weeks and are chaired by the President. The Board makes formal

decisions concerning investments, technical co-operation assignments, borrowing

and other Bank activities. Importantly, it also has the task of

monitoring compliance with the political aspects of the Bank’s mandate.

Should the Board express serious concerns over a country's compliance,

it might decide to limit the Bank's involvement with the State,

while remaining engaged in the private sector to support economic

transition.

18. This policy, known as the calibrated approach, currently concerns

two countries, Belarus and Turkmenistan. The Board of Directors'

decisions are determined by majority voting, provided that the said majority

represents no less than two-thirds of the subscribed shares in the

Bank's capital. The Board is composed of 23 Directors, each representing

one or more members. Only a few countries of operations are directly

represented in the Board by their own Director. However, in April

2013, some Governors asked for a reconsideration of the composition

of the Board of Directors, with the aim of increasing the weight

of recipient countries. This process would be concomitant with the

Bank's Fifth Capital Resources Review.

19. The Bank's day-to-day business is carried out in 13 departments.

Banking, Finance and Risk are responsible for lending, borrowing,

and risk-management activities. The provision of legal advice and operational

support falls within the competence of the Office of the General

Counsel, while the Office of the Secretary General administers the

Bank's institutional relations, in particular with its shareholders.

Perhaps, however, what most characterises the EBRD as a unique financial

institution are the External Action and Political Affairs department

(EAPA) and the Office of the Chief Economist (OCE).

20. Although all the Bank's activities are directed towards promoting

transition, it is within these two departments that both economic

and political progress is monitored and assessed. The OCE is responsible

for economic analysis; in particular, it evaluates the potential

impact of the Bank's individual projects in fostering transition

to a market-oriented economy. The OCE also assesses the degree of

economic transition achieved at sector and country levels. Political

transition is monitored by the EAPA, which provides regular updates

and insights into political developments in the countries of operations.

Its advice is instrumental in order for the Bank to carry out its

policy dialogue initiatives. Furthermore, the EAPA is also responsible

for the management of the donor-funded activities, which include

technical co-operation with the Bank's clients and policy dialogue

with recipient countries.

21. Alongside the political and economic assessments provided

by the EAPA and OCE, the crucial task of evaluating the Bank's effectiveness

in delivering transition is carried out at the Evaluation Department

(EvD). The EvD operates in complete independence from the rest of

the Bank's management and reports directly to the Board of Directors.

Through the provision of an independent and evidence-based assessment

of its performance, its evaluations contribute to strengthening

the Bank's performance and institutional accountability. A relevant

part of the EvD activities consists of the

ex

post evaluation of the transition impact of the Bank's

projects, with respect to private sector development achieved and

improvements at the institutional and policy levels. The activities

of the EvD, however, are not confined to the evaluation of individual

projects; they also include the evaluation of the Bank's strategies,

programmes and policies. A thorough overview of the EvD's work is

provided in the Annual Evaluation Review.

22. The Bank also supports transition by promoting the highest

standards of corporate governance, transparency, and integrity in

its region of operations. The responsibility for overseeing the

application of these standards lies with the Office of the Chief

Compliance Officer (OCCO). The OCCO, which answers to the President

and the Audit Committee of the Board of Directors, evaluates the

integrity and transparency of the Bank's clients and assesses the

hypothetical reputational risks associated with its investment activities.

As part of its tasks, the OCCO investigates allegations of fraud

and corruption arising in relation to the Bank's projects. Equally

important, it also administers the Project Compliant Mechanism (PCM),

which allows individuals and local groups in the countries of operations

to raise grievances or complaints in relation to EBRD projects. Moreover,

the OCCO is responsible for the application of international best

practices and standards also in relation to the Bank's internal

conduct.

23. As part of its commitment to democracy and good governance,

the EBRD regularly engages with a variety of civil society organisations.

Dialogue with the civil society concerns both individual projects

and more encompassing initiatives, including the review of the Bank's

key policies and strategies. In December 2013, the EBRD approved

the new Energy Sector Strategy, which will govern the Bank's investments

in the energy sector from 2014 to 2018. Crucially, its approval

followed an extensive consultation process with more than 1 000 organisations,

during which the Bank incorporated and responded to comments from

external stakeholders.

The

President and members of the Board of Directors also hold meetings

with civil society organisations and other key stakeholders during

their visits to the countries of operations.

24. Soon after his election, in 2012, President Chakrabarti unveiled

a modernisation agenda, which aims to make the internal organisation

more responsive to the ever-changing challenges that the Bank will

face in the future. The initiative, which was denominated

One Bank, focuses on the need to

streamline the Bank's internal procedures and modernise its management

culture. The Bank foresees achieving further efficiency gains through

the adoption of several measures, including the reduction of underperforming

staff and of allowances for travel and missions. The most concrete

result of the Bank's modernisation initiative was perhaps the creation

of two new vice-presidencies in 2012, one for policy and one for

human resources and corporate services. In this context, in 2013

the EBRD identified a set of core values – professionalism, integrity, leadership,

innovation, diversity and teamwork – which could contribute to improving

the management of the Bank's staff. This led the EBRD to enhance

inclusion and diversity among its staff by joining diversity programmes

and networks and by introducing compulsory training on inclusive

leadership. The Bank also expanded the project selection criteria,

with the aim of becoming more effective in areas of social inclusion

and equal opportunities.

25. The establishment of the Vice-Presidency for Policy had highly

symbolic and operational relevance, since it constituted an important

part of the Bank's overall effort to re-energise transition via

enhanced policy dialogue. The aim is to use policy dialogue to achieve

transition impact going beyond individual projects by, for example,

strengthening the link between the Bank's investments and the economic

reforms to be adopted at the broader sector and country levels.

In

this respect, in May 2014 the Bank accomplished a remarkable achievement

by signing the Partnership for Re-energising the Reform Process

in Kazakhstan with the Kazakh authorities. The partnership enables

the EBRD, together with other international financial institutions,

to channel US$2.7 billion provided by the government into strategic

sectors of the economy. This will increase the Bank's critical mass

in the country, thereby providing enhanced opportunities for policy

dialogue and technical co-operation. According to the EBRD Managing

Director, Olivier Descamps, the partnership may become an important

way to boost market reform and, if successful, it may constitute

a blueprint to re-energise transition in other middle-income countries.

26. The EBRD has been criticised recently for its lack of transparency.

In 2013, the EBRD was ranked by the Aid Transparency Index (ATI)

as the lowest among 67 International Financial Institutions and

multilateral organisations in respect of transparency. According

to the ATI, the Bank “lags on commitments indicators and on organisation

and activity financial information”. The Parliamentary Assembly

should therefore encourage the EBRD to join the International Aid

Transparency Initiative (IATI) and to start publishing data to IATI standards.

4. Political and economic

developments in 2013 and 2014

27. In its 2013 Annual Report, the EBRD noted that since

the early 2000s a number of countries in the transition region had

seen a levelling off of democratic progress.

Later, the financial crisis

triggered a sense of resentment towards market economy, which had

delayed the implementation of reforms. The intertwining of the two

processes led the EBRD to define some of its countries of operations

as stuck in a lower-than-optimal level of political and economic

reform.

In

the second half of 2013 and the first half of 2014, episodes of

public discontent calling for better governance occurred in several

countries across the transition region. Social unrest has temporarily

increased political uncertainty, which in some countries is hindering

economic activity. On the other hand, however, these episodes offer

an important window of opportunity to rekindle the reform agenda. Crucially,

the chances of success in unleashing a new wave of political as

well as economic reforms also depend on leadership and external

support. It is in these areas that the EBRD maintains an instrumental

role.

4.1. The EBRD region

between democratic progress and geopolitical tensions

28. In 2013 and 2014, political developments in the EBRD

region have seen mixed results. While the escalation of geopolitical

tensions between Russia and Ukraine and the challenges in the political

transition of Egypt and Tunisia dominated events, democratic progress

in a number of other countries was tangible. On 1 July 2013, Croatia

officially became the 28th member of the European Union. Georgia

and the Republic of Moldova signed an Association Agreement with

the European Union in 2014. Notable democratic progress was also

evident in countries of the Central Asia region, particularly in

Mongolia and in the Kyrgyz Republic. In April 2014, the Parliamentary

Assembly granted Partner for Democracy status to the Parliament

of Kyrgyzstan.

29. In the Western Balkans region, the process of reconciliation

between the different countries continued, although significant

challenges stemming from inter-ethnic issues remained. In February

2014, a series of demonstrations and social unrest rapidly spread

in Bosnia and Herzegovina, with the population demanding an end

to the political inertia that had characterised the country since

the end of the war. The deep-rooted causes of the government's failure

to act could be found in the fragile constitutional equilibrium

that had emerged from the pacification process following the war

in the former Yugoslavia. This provided the country with a complex

system of checks and balances which hampers an efficient functioning

of the State. In the Country Strategy adopted in January 2014, the

EBRD indicated the reform of the country's constitutional set-up

as a pivotal step to progress towards a more efficient and democratic

State.

30. In Turkey, the government reacted firmly to manifestations

of public discontent following the demolition of Istanbul's Gezi

Park in May 2013. This caused a wave of protest, mainly against

alleged limitations to the freedom of expression and assembly, to

spread around the country. In December 2013 and in the first months of

2014, a corruption scandal involving associates of some government

ministers unleashed new public protests, to which the government

responded by temporarily limiting access to social media. In March

2014, however, the ruling party won local elections in the most

important cities of the country, and the level of social unrest

gradually decreased. The EBRD remains firmly committed to addressing

the remaining transition gaps in the country.

31. Apart from the progress in the Republic of Moldova, developments

in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) raised concerns,

particularly with respect to corruption, weak adherence to the rule

of law and instances of human right violations reported by international

organisations. The lack of democratic progress in Belarus and Turkmenistan

was especially noted as a cause of serious concern in the 2013 Annual

Report.

The scope of

the Bank's engagement in those two countries is limited to specific

sectors of the economy and is defined against a well-specified set

of both political and economic benchmarks, in the context of the

so-called calibrated approach.

32. The EBRD responded to the developments which occurred in the

first part of 2014 in Ukraine by stating its readiness to step up

both its financial engagement to the country and its policy dialogue

initiatives with the authorities. The Bank's investments in the

country are expected to increase to €1 billion per year, as part

of an international financial assistance programme.

In May 2014, the EBRD signed a Memorandum

of Understanding with the government for the Ukrainian Anti-Corruption

Initiative. At the heart of the initiative, which aims to monitor

corruption and increase transparency, is the creation of an independent

Business Ombudsman Institution, to which businesses can bring their

complaints of unfair treatment.

33. As for its engagement in Russia, the EBRD did not make any

formal decision regarding the scope of its operations in the country

following the Crimean crisis. However, the Russian economy is expected

to decelerate as a consequence of the escalation of the geopolitical

tensions. This might cause the volume of EBRD investments in the

country, which had already slumped from €2.6 billion in 2012 to

€1.8 billion in 2013 because of deteriorating investment conditions,

to decline further. During his address to the 2014 Annual Meeting,

President Chakrabarti emphasised the concept of managed flexibility,

which allows the Bank to reallocate to other countries the spare

capacity resulting from lower investments in one region.

34. In the SEMED, political reforms proceeded steadily, albeit

with some difficulties. In Jordan and Morocco, the role of elected

parliaments was strengthened by the adoption of further reforms.

Following a period of stalemate, in February 2014 Tunisia approved

the new Constitution, which was seen as an important step in the

country's transition to democracy. In Egypt, progress was more uneven.

The political transition following the 2011 uprising was interrupted

by mass demonstrations against elected President Mohamed Morsi. Following

his deposition in June 2013, a prolonged period of political tensions

and social unrest ensued. A new road map for the transition process

was finally agreed upon in December 2013. This resulted in the approval of

the new Constitution in a referendum in February 2014, and in the

election, at the end of May 2014, of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi as the

new President of the Republic. Parliamentary elections are to be

held in October 2014. Despite the period of political uncertainty,

the EBRD made significant progress in carrying out its operations

in the SEMED region. Although Egypt maintained the status of potential

recipient country, the Bank had been investing in the economy through

the ad hoc EBRD SEMED Investment Special Fund. Meanwhile, Jordan, Morocco

and Tunisia were granted recipient country status in November 2013.

The Parliament of Morocco was granted Partner for Democracy status

by the Parliamentary Assembly in 2011 and the Parliament of Jordan has

also submitted a request for such status.

4.2. Heightened uncertainty

and the risks to the outlook for growth

35. With the exception of Russia, Turkey and Poland,

the transition region is formed of countries of a relatively small

economic size, which makes them vulnerable to external developments.

This was evident in the aftermath of the financial crisis, as the

region was hit particularly hard by the collapse in global trade

and by the withdrawal of foreign capital. Whereas trade rebounded

in 2009-2010, the process of cross-border deleveraging, in which

foreign-owned banks withdraw funding from the transition region,

was still ongoing, albeit at a slower pace. Overall, economic output

expanded by less than 3% in both 2012 and 2013. In May 2014, partly

as a consequence of the tensions between Russia and Ukraine, the

Office of the Chief Economist forecast it to further decline to

1.4% in 2014.

36. Analysing the dynamics of growth in closer detail, it appears

that in 2013 the decrease of financial tensions in the Euro Area

benefited countries with close links to the monetary union. The

gradual recovery in economic activity in the Euro Area was reflected

in substantial higher growth rates in the South East Europe (SEE)

region, averaging 2.7% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2013 compared

to 0,4% in 2012. This was despite the fact that cross-border deleveraging

had not come to a halt in the SEE region and in central Europe and

the Baltic States (CEB), thus further delaying the resumption of

credit growth. On the positive side, however, deleveraging mostly

took place in the form of foreign currency lending, while local

currency lending, which does not expose the borrower to exchange

rate fluctuation risks, increased in a number of countries, including

Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria and “the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia”.

Political uncertainty, however, was a key factor in affecting growth

in other regions of EBRD operations. In Ukraine, the beginning of

social unrest in the last months of 2013 contributed to further

deteriorating the already weak consumer and business confidence,

with output stagnating in 2013. Output growth in the SEMED region

in 2013 was slightly below expectations, due to a mix of domestic

and regional turmoil.

37. Economic expansion was dampened in eastern Europe and the

Caucasus (EEC), as the worsening of the external environment, which

before was confined to the western part of the transition region,

expanded eastwards. This was mostly due to developments in the global

economy. In May 2013, the American Federal Reserve Bank announced

that it would soon start to scale down the so-called quantitative

easing, a large-scale asset purchase programme that it had carried

out during the five preceding years in response to the financial crisis.

As quantitative easing had contributed to increasing short-term

capital flows to emerging market economies, the mere announcement

of its scaling down, known as tapering, caused volatility in the

financial markets of these countries to increase, and financial

flows to reverse. Partly as a result of heightened uncertainty about

future swings in global monetary policy, key emerging markets, including

China, India and Russia, experienced a slowdown in economic activity,

thereby contributing to weakening external demand in neighbouring

countries. In the third quarter of 2013, net private capital flows

turned negative in the EBRD region. Increased volatility and the

reversal of capital flows were particularly evident in the depreciation

of the currencies of those countries that were dependent on capital

flows from abroad, such as the Turkish lira and the Mongolian tögrög,

which lost about 15% of their value against the US dollar in the

seven months between 13 May and 13 December 2013.

38. With the exception of the SEE and the SEMED regions, which

should benefit from the recovery in Europe, the outlook for economic

growth in 2014 and 2015 in the transition region has been negatively

affected by the geopolitical tensions between Ukraine and Russia.

As the Crimean crisis escalated, volatility in the financial markets

heightened. Capital flights out of Russia in the first quarter of

2014 reached the overall level registered in the whole of 2013.

The downward pressure on the Russian rouble intensified, while the

domestic stock market plunged. As a result, investor and business

confidence has worsened, and economic growth is forecast to come

to a halt in 2014, and to remain low in 2015. In Ukraine, the depreciation

of the currency and the jump in the country-risk indicators only

became subdued in early May 2014, after the government signed a

preliminary agreement on an international macroeconomic adjustment

programme led by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). As a result

of the implementation of the structural reforms envisaged in the

programme, Ukraine is expected to suffer severe output losses in

2014 and stagnation in 2015.

39. Increased geopolitical tensions between Russia and Ukraine

are also likely to impact neighbouring countries. The EEC region

is forecast to suffer from direct negative financial and economic

spill-over from the crisis. In May 2014, the Office of the Chief

Economist revised its forecast for growth in the region for 2014

to -2.6% of GDP, from +2.0%.

In

the CEB region, increased geopolitical tensions are likely to neutralise

the positive effects stemming from the pick-up in external demand

coming from the Euro Area and the first sign of recovery of private

investment. The Crimean crisis could affect growth in the region,

mostly through trade links with Russia and due to energy security

concerns, resulting from gas supply uncertainty. The EBRD forecasts growth

in the CEB region to be 2.2% of GDP in 2014. In the Central Asia

region, the outlook was dampened by two factors: the slow-down in

remittance growth coming from Russia and the contagion in the financial

and currency markets, which was already evident in the devaluation

of the currencies of countries with close links with Russia, such

as the Kyrgyz Republic and Kazakhstan. However, the EBRD still expects

growth in the Central Asia region to average 6.2% in 2014.

40. As far as macroeconomic policy is concerned, developments

in the transition region in 2013 and 2014 reflect broader global

trends. Monetary policy remains accommodative in most EBRD countries

of operations, also thanks to declining inflation rates. Declining

inflation, in turn, is caused by lower commodity prices, weaker growth

in key emerging markets and high unemployment in developed economies.

Notable exceptions are Russia and Turkey, where inflation remains

above the central bank's goal. Evidence on fiscal policy is more mixed.

Consolidation efforts continue in all European Union member States,

with the aim of complying with the European Union fiscal rules.

However, the primary balance, a measure of the fiscal stance of

the government, deteriorated in some countries as a result of the

decrease in revenues caused by slowing economic activity. Primary

balance deteriorated also in a number of commodity exporting countries,

due to lower commodity-related revenues. Fiscal deficits remain

relatively high in Egypt and Tunisia, due to an increase in spending and

the failure to reform energy subsidy schemes.

5. Transition fatigue

and the response of the EBRD

5.1. The legacy of slower

growth: declining public support for market-oriented reforms

41. The prolonged period of slower growth that has followed

the global financial crisis has profoundly affected the prospects

of the EBRD transition region to achieve convergence with the living

standards of advanced market economies. The main economic reason

that has caused growth in the transition region to slow and remain

below pre-crisis levels is well understood and lies in the persisting

decline of international capital flows to the region. According

to the Office of the Chief Economist, however, the cure for the

economic malaise should not be a return of capital flows to pre-crisis

highs, since in many cases these reflected unsustainable investment

bubbles. Rather, a more pressing concern is the lack of political

resolve to implement those structural reforms that are crucial to

improve market-supporting institutions and rekindle growth. As noted in

the 2013 Transition Report, reforms had already been losing momentum

since the mid-2000s, before the financial crisis hit, and the period

of slower growth following the financial crisis further exacerbated

this structural problem.

42. The increase in long-term unemployment brought about by the

crisis and the prolonged period of fiscal austerity, often recommended

by supranational bodies, is eroding public support for market-oriented

reforms. Some of the most advanced countries in the transition region

even experienced reform reversals. For instance, Hungary and Bulgaria

have seen administrative tariff reductions, pushing energy prices

below cost-recovery levels. This risks deterring investment in the

sector, thus undermining economic competitiveness. Delays in privatisations,

the re-nationalisation of banks and increased State interference

in the economy occurred in a number of countries, including Russia,

Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Latvia. In Poland and Hungary, capital market development

suffered from a setback when the governments passed legislation de facto eliminating the fully-funded

private leg of the pension system.

43. The Office of the Chief Economist has developed the so-called

transition indicators, in order to assess progress in transition

to an open market economy. At country-level, there were 11 downgrades

across the EBRD transition region between 2010 and 2013, of which

six concerned European Union members. During 2013, downgrades outnumbered

upgrades across the EBRD transition region for the first time since

the Bank's establishment.

The

fact that the majority of downgrades affected the most advanced

countries comes only partially as a surprise. Due to the close links

with western Europe, the crisis is felt the most in the CEB and

SEE regions. In addition, in many of these countries the crisis

appears to have been blamed on the economic institutions prevailing

at the time, thus denting support for free markets. However, structural

reforms are seen as a crucial element for achieving convergence.

According to long-term forecasts made by the Office of the Chief

Economist, if countries did restart reforms, yearly growth could

increase between 0.8% and 1.5% of GDP over the longer term. The

policy challenge lies in the fact that, in order to rekindle growth,

it is necessary to whet the appetite for structural reforms. However,

this needs to be accomplished during a period in which the support

for reforms has declined, precisely because of slow growth.

5.2. Re-energising transition:

medium-term directions and the Fifth Capital Resources Review

44. During the 2014 Annual Meeting, President Chakrabarti

unveiled a three-pronged approach jointly devised by the Board of

Directors and Senior Management to re-energise transition in the

EBRD region. This approach is part of a more comprehensive strategy

defined as “medium-term directions”, which constitutes the basis

for the discussion over the

Fifth Capital

Resources Review, covering the period 2016 to 2020. In presenting

the medium-term directions, President Chakrabarti noted that in

order to deliver most effectively the Bank has to fine-tune its

business model and he made an explicit reference to the need to

enhance the Bank's risk-taking capacity.

45. The new strategy develops around three key points: the first

one concerns the need to build resilience in the transition process,

especially in terms of institutions and economic structures. At

the EBRD, the necessity to revitalise the appetite for market reform

in order to rekindle transition is well understood. Ultimately,

however, it is the role of governments to adopt the policies that

are necessary to foster transition. Despite that,

the Bank still has a decisive role

to play in formulating and bringing forward those policies. Furthermore,

thanks to its long experience in the region, the Bank is in a privileged

position to pinpoint and provide finance to those projects that

could have a sustainable impact on transition, because the right

policies and institutions are in place. The medium-term directions

regard precisely these two elements, the formulation of policy reforms

and the financing of pivotal projects, as the way forward for the

Bank to contribute to improving economic structures and institutions.

46. The second aim of the medium-term directions consists of developing

further economic integration in the transition region. Besides raising

growth, integration could also help to prevent reversals in the

transition process, as the costs of undoing reforms are higher in

more interconnected economies. Concretely, the Bank could intervene

in this sector in two ways, by providing financing to projects aimed

at developing cross-border infrastructures and by introducing new

international investors to the region.

47. Finally, the need to address common global challenges, such

as food security, climate change, water scarcity and energy security

constitutes the third main point of the strategy.

The

EBRD has already been tackling these challenges and aims to further

strengthen its engagement. For example, the Bank reacted to the increase

in food prices between 2010 and 2012 by increasing its investments

in the agribusiness sector. Furthermore, with the objective of reducing

carbon emissions and making the countries of operations more energy

efficient and independent, in 2006 the EBRD launched the Sustainable

Energy Initiative, through which it invested €13.5 billion in sustainable

energy projects between 2006 and 2013.

48. The medium-term directions are not confined to the three points

referred to above. An important aspect of the new strategy concerns

the Bank's geographic planning. In this respect, the medium-term

directions present a consensus view on gradually phasing out investments

in the seven EBRD recipient countries that joined the European Union

in 2004, in the context of the so-called “graduation” policy. It

is not yet clear, however, whether graduation is foreseen to take

place within the period of the Fifth Capital Resources Review. In

order to make the graduation process smoother and politically attractive,

the Bank is also working to devise a new Post-Graduation Special

Fund to which countries can access after graduating to get financing

for cross-border investment projects. This fund will also benefit

the Czech Republic, which is the only EBRD member to have already

effectively graduated in 2007. Whereas the Bank expects to gradually

scale down its operations in the western part of the transition

region, the medium-term directions maintain the general orientation

towards increasing operations in the east and south of the region.

Finally, the new approach to geographic planning also aims to increase

the Bank's flexibility in responding to changes in the business

environment across the region. Importantly, the scope of increased

flexibility would always be determined under the guidance of the Board

of Directors.

49. The Bank is also working to modernise its planning process.

Concretely, this consists of the introduction of a Strategic Implementation

Plan (SIP), on a three-year rolling basis. Currently, the guidelines

for the activities of the Bank over the medium term are outlined

in the Capital Resource Review (CRR), which covers a five-year period,

whereas implementation is defined in the Annual Business Plan (ABP).

A drawback of this approach is that it does not leave much room

for changes in the Bank's strategic direction. As a result, in some

cases the Bank had to deviate from the original plan set out in

the CRR. The most notable example was the postponement of the graduation

of the recipient countries that joined the EU in 2004, which was

expected to take place within the period covered by the Third Capital

Resources Review (2006-2010). The intention of the reform is to

make the planning process more flexible by allowing the SIP to draw

some of the work out and ease the burden of the CRR and the ABP.

This would make the CRR less prescriptive, thereby contributing

to improving the alignment between the Bank's priorities and the

constraints posed by the environment in which it operates.

6. Democratic progress

of recipient countries

50. In February 2013, the EBRD updated the processes

and procedures concerning the implementation of the political aspects

of its mandate. The Bank's operations, which are designed to foster

private sector development and narrow economic transition gaps,

are only indirectly targeted to the promotion of democratic transition.

It follows that the Bank neither assesses the potential contributions

nor evaluates the impact of individual projects for the development

of multiparty democracy. Nevertheless, democratic progress is recognised

as being closely interrelated to the main purpose of EBRD operations,

namely to foster transition to an open market economy. For this

reason, political assessments are an integral part of the triennial

Country Strategies and of the annual Country Strategy Updates.

6.1. Does market reform

promote democracy? Theory and evidence from the transition region

51. Market reform is typically thought to have both broad

political and institutional implications. More specifically, economic

development is often associated with the consolidation of democratic

institutions and institutional capacity building. However, economic

transition and democratic progress do not always come together.

In particular, whereas the correlation between economic development

and democracy is significant, such correlation does not need to

imply a causal relationship.

52. To the extent that the EBRD mandate is to foster transition

to an open market economy in those countries committed to the principles

of multiparty democracy, the nature of the relationship between

economic and political development acquires a critical relevance.

If economic and political transition were known to be two unrelated

processes, the EBRD could be expected to operate only in those countries

that were already applying the principles of multiparty democracy.

On the other hand, in the case that market reform was to benefit

political transition to more democratic systems, the EBRD could

be legitimately thought to carry out its operations also in non-democratic

countries. In reality, the Bank is active both in fully democratic

countries, such as those belonging to the European Union, and in

less democratic ones, such as Belarus and Turkmenistan, suggesting

that political transition is to benefit from economic development.

53. When the Sub-Committee on Relations with the OECD and the

EBRD met at the headquarters of the EBRD in February 2014, we asked

in particular how the Bank handled the fact that it was helping

countries which were not working towards democracy, and bringing

credibility to certain countries which did not deserve it. We were

told that although the aim of the Bank was not to foster democracy

and experience had shown that democracy and market economy did not

always go together, it was nevertheless hoped that they would converge

in the long term. We were also told that the EBRD Board had felt

that walking away from such countries would not help them.

54. The 2013 Transition Report dedicates an entire chapter to

reviewing the literature explaining the relationship between markets

and democracy and tests whether its main findings apply to the transition

region. A large strand of the literature finds wealth, industrialisation,

urbanisation and education to be statistically associated with the

development of democratic systems. Building upon this finding, the

well-known modernisation theory regards economic development, as

measured in per capita income level, to be critical for the creation

of a wealthy and politically active middle class, which demands

and supports democratic reform. Another important channel through

which economic development is thought to benefit democratisation

consists of the higher level of educational achievement that typically

characterises countries with higher GDP per capita, the reason being

that education positively influences the perception of individuals

about democracy.

55. On the other hand, another strand of literature holds the

view that it is economic equality, rather than economic development

per se, that makes democratic systems more likely to come about

and later survive. In particular, in an unequal country the small

minority controlling most of the wealth would prefer an authoritarian regime

acting in favour of the minority, rather than a democratic one operating

in favour of the majority. Of course, this is contingent upon the

assumption that the less well-off majority would seek redistribution

through the ballot box and the tax system if it were given the possibility

to do so, as in the case of democratic systems.

56. Using international data, the 2013 Transition Report empirically

investigates the relationship between economic and democratic development

and concludes that market reform and economic growth globally appears

to benefit democratisation in the long term and reduce the chances

of democratic regression. Specific evidence from the transition

region is more mixed. Over a longer period, the impact of economic

growth on democratic development was not significant. This is not

surprising, however, since most countries in the EBRD region experienced

economic development but remained part of undemocratic States or

empires as late as 1989. The picture changes considerably when only

the period between 1989 and 2012 is considered. The 2013 Transition

Report finds that democratic development depended strongly on lagged

economic growth, and perhaps more importantly on the adoption of

market reforms. Note that the level of economic equality, as measured

by the GINI coefficient, does not seem to have played a decisive

role.

57. There are, however, a few caveats. Globally, countries with

large endowments of natural resources are found to be less likely

to develop a democratic system even when economic development is

achieved. This also applies in the EBRD region. There, countries

having a high share of GDP stemming from natural resource extraction

are substantially less democratic than their level of economic development

would otherwise predict. The large revenues generated by extractive

industries make the authorities less dependent on a fiscal system that

taxes the general population, which in turn decreases the pressures

to enhance accountability to the taxpaying population through the

development of more democratic institutions.

58. Furthermore, the large revenues related to natural resource

extraction allow the authorities to maintain consensus by redistributing

subsidies to the population, thereby reducing the demands for political

reform. Since some of its recipient countries are endowed with large

stocks of natural resources, the fact that this might impede democratic

development is particularly relevant for the Bank's policy. The

Bank's engagement in such countries is particularly focused towards

institutional capacity building, via increased policy dialogue and economic

diversification. The latter, which is promoted by financing projects

in sectors other than those related to natural resource extraction,

is crucial to develop other sectors of the economy, thereby making

the population less dependent on the subsidies distributed using

revenues related to extraction. The development of sound institutions

is essential to guarantee that the windfall revenues stemming from

resource extraction are used to finance productive investments that

are beneficial for economic growth, rather than for consensus-seeking

redistribution.

59. The 2013 Transition Report also finds that the effects of

economic development on democratisation are likely to take between

one or two decades to materialise. In the short term, economic growth

could even increase the chances of survival of non-democratic regimes.

Therefore, the international development community needs to act

with patience and persistence in supporting market reform, as this

would only gradually promote democratic progress.

6.2. Degree of achieved

transition in recipient countries relative to quantity of EBRD investments

60. The lack of an assessment of the potential contribution

of individual projects in fostering democracy increases the difficulty

in establishing a causal relationship between the volume of the

EBRD investments in a recipient country and the degree of democratic

transition achieved. On the other hand, a simple comparison of relevant

democratic governance indicators between 1992 and 2012 suggests

that a few countries in the EBRD region have made significant progress

in their level of democratic development.

61. Figure 1 presents a chart showing changes in the level of

democracy, as measured by Polity scores, between 1992 and 2012,

both for countries in the transition region and others. The Polity

project provides a series of data widely used in social sciences

research. Its analysis focuses on the most formal class of polities, that

is States operating within the modern world's State system. Democracy

is conceived as the presence of three interdependent elements: the

existence of institutions and procedures through which citizens

can express effective preferences about alternative policies and

leaders; constraints on the exercise of power by the executive;

and the guarantee of civil liberties.

62. Polity's conclusions about a State's level of democracy are

based on an evaluation of: i) competitiveness of executive recruitment;

ii) openness of executive recruitment; iii) constraints on the chief

executive; and iv) competitiveness of political participation. A

Polity score ranging from -10 to +10 is determined for each year and

country. Values from -10 to -6 are used to classify autocracies,

-5 to 5 for anocracies, and 6 to 10 for democracies. Countries above

the dotted line experienced improvements in democracy, those below worsened.

Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan were already so undemocratic in 1992

that they could not get any worse and maintained their position

at the bottom. Belarus, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, by this order,

had the worse evolutions, with Belarus dropping 15 points from +7

to -7. Kyrgyzstan had one of the more positive changes, rising from

-3 to +7.

Figure 1: Changes in the level

of democracy between 1992 and 2012

Source: EBRD 2013 Transition Report, p. 26

63. By 1992, democracy had already developed in most

of the countries that would join the European Union in 2004, which

prevented them from experiencing further significant improvements

in the period considered. It is not surprising that democracy had

sprung up in the western part of the transition region soon after

the fall of the Berlin Wall; thanks to a well-educated population

and a largely manufacturing-based economy, the right environment

for democratic development to flourish was already in place in these

countries. The fall of the wall then constituted the right window

of opportunity for an orderly political transition to take place.

A similar story holds for the countries of southern and eastern

Europe, whose transition to democracy mainly came about following

a large shock, such as the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia.

On the other hand, Russia and Ukraine started with relatively high

democratic indicators in 1992 but failed to develop further. This

possibly reflected how a combination of the old elite and a new

class of political entrepreneurs managed to preserve or take control

of strategic sectors of the economy, including those involving natural

resource extractions.

64. The Central Asian republics perhaps constitute the most interesting

case to analyse. These countries started their transition with a

relatively low level of democratic development and had a largely

agrarian and resource extraction-based economy. Some, like Uzbekistan

and Turkmenistan, have experienced virtually no change, whereas

in other countries democratic indicators either substantially improved

(as in Mongolia and the Kyrgyz Republic) or declined (as in Kazakhstan

and Azerbaijan). With the exception of the Kyrgyz Republic, the

rate of EBRD investment in the central Asian region seems to be

somehow correlated to the countries’ democratic performance.

65. Crucially, Mongolia had the highest EBRD investment rate in

the transition region, as the Bank invested on average €32 per year

per person in the eight years of operations in the country. The

same figure is only €1 and €2 for Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, respectively.

High annual per capita investment rates, between €18 (in Slovenia)

and €29 (in Montenegro), also characterise countries in the SEE

region, which all realised improvements in their democratic indicators

between 1992 and 2012. In Belarus, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, the

countries with the most negative changes in democracy indicators,

the EBRD investment rate is respectively €7, €10 and €14 per year

per person.

66. To some extent, these numbers indeed suggest the existence

of a positive correlation between the Bank's investments in recipient

countries and the degree of democratic progress achieved. It should

be noted, however, that these are very rough figures and do not

take into account important aspects, such as country’s economic

size and potential reverse causality issues.

They are therefore not meant

to infer a causal relationship between EBRD investments and democratic

progress.

7. Special issues

regarding EBRD activities

7.1. Operations in the

southern and eastern Mediterranean region: an early review

67. The political breakthrough in the SEMED countries

in 2011 was the result of a home-grown process rather than of external

developments. After a long period of non-democratic rule, mass protests

calling for more equality of opportunities initiated an era of change.

The events that followed offer a unique window of opportunity to

foster both economic and political development.

68. The success of the transition process, however, depends on

several factors. Issues in the new transition region are quite different

from those in east European countries in the 1990s, which makes

the SEMED a unique case for the EBRD. The stock of human capital

in the region is slightly below that of CEB and SEE countries when

they started their transition. This could increase the time needed

to develop those political, legal and economic institutions that

are crucial to foster development. Moreover, the young unemployed

constitute a large share of the population in the SEMED, which makes

political reform more susceptible to regression in the event that

they do not feel sufficiently included in the transition process.

69. On the other hand, private sector development, particularly

that of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and the modernisation

of the infrastructures and energy distribution systems constitute

two areas with large transition impact potential where the EBRD

could play an important role. Another area where transition gaps

are evident relates to female participation in the labour market

and more specific gender issues. In this connection, the Bank recently

added economic inclusion as one of the areas to be considered in

its assessment of transition. Economic inclusion, intended as the

extension of opportunities to individuals regardless of their circumstances

or social background, could contribute to increasing female and

youth participation in the labour market.

70. Following the shareholders’ agreement to extend the Bank's

geographic remit to include Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia and Jordan,

the EBRD has carried out preliminary work to understand country

priorities and, since 2011, develop first contacts with stakeholders.

In 2012, the Board of Governors allocated €1 billion from the Bank's

net income into the SEMED Investment Special Fund, to implement

early investments in the region. Following the approval of potential

recipient country status for Egypt, Tunisia, Jordan and Morocco,

the first project in the SEMED was approved in December 2012. In

November 2013, Tunisia, Jordan and Morocco were granted the status

of recipient country, while Egypt still remains a potential recipient

country. Furthermore, the Bank opened resident offices in Tunis,

Cairo, Casablanca and Amman, to cultivate relationships with the respective

authorities and business communities.

71. Three years after the events of the Arab Spring, the EBRD

is fully engaged in the new transition region and intends to significantly

expand its financial and institutional commitments. Crucially, the

EBRD is also engaged with the authorities in policy dialogue activities,

with the particular aim of developing the legal environment. Overall,

in 2013 the Bank invested €449 million in 21 operations in the region.

The EBRD, however, expected its investment volume to increase up

to €2.5 billion by 2015. The EBRD identified five main priority

areas consisting of: i) supporting SMEs development, in order to

achieve a major impact on growth and job creation; ii) enhancing

the agribusiness value chain by improving yields, logistics and

resource efficiency; iii) assisting financial institutions through

capacity building and product innovation; iv) supporting the governments

in gradually liberalising the energy sector and introducing energy

efficiency and sustainability practices in the economy; and v) modernising

the infrastructure system, also via decentralisation of municipal services

and the involvement of the private sector.

7.2. The relations between

the EBRD and the European institutions

72. Ever since it was set up, the EBRD has dedicated

itself to cultivating its relations with other international organisations,

and European institutions in particular. The Bank has regular contacts

with the Council of Europe, the Council of Europe Development Bank

(CEB), the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Commission.

The relationship between the EBRD and the Council of Europe is directed

at monitoring democratic progress in central and eastern Europe.

Additionally, in October 2013 the EBRD and the CEB updated an existing

bilateral agreement which foresees regular exchanges of information

in order to facilitate collaboration in areas where their mandates

overlap and enhance impact in common countries of operations. When

we met at the EBRD, Sir Suma Chakrabarti expressed his appreciation

for co-operation with the Assembly's Monitoring Committee.

73. The relation between the EIB and the EBRD has a unique characteristic,

insofar as the EIB is an EBRD shareholder, but not vice versa. The

two banks have shared interests in several of the EBRD countries

of operations and often co-finance the same projects. In 2011, the

EBRD, the European Commission and the EIB updated an already existing

Memorandum of Understanding, aimed at supporting the fulfilment

of European Union external policy objectives in the countries where

both banks operate.

74. The European Union is itself a shareholder in the EBRD, as

are all EU member States. Furthermore, both EU member States (such

as Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania,

Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia), and EU candidate and potential

candidate countries (such as Albania, Bosnia Herzegovina, Montenegro,

Serbia and “the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia”) are also

EBRD recipient countries. European partners, such as the European

Commission, the EIB, and some EU member States, are among the largest

donors for crucial EBRD activities, such as technical co-operation

with the Bank's clients and policy dialogue with the governments

of recipient countries. Through these activities, the Bank improves

standards in corporate governance and transparency and promotes

the development of market supporting institutions in key transition

sectors of the economy. A new development in the EBRD activities

was the establishment in 2013 of an External Policy Coordination

Team and the opening of an office in Brussels, which aim to further

enhance collaboration with the European institutions and other key

external partners.

8. Conclusions

75. Before the recent financial crisis of 2007-2008,

the transition to market economy was considered to have been broadly

achieved throughout a significant part of the EBRD region. The severe

recession that followed jeopardised the convergence process and

challenged the results achieved in previous years. Due to the diminished

availability of foreign capital and the related credit crunch, investments

and consumption suffered, which had a negative impact on economic

growth. The crisis and the continued efforts towards fiscal adjustment

in the European Union countries also dented public support for free

markets. In this context, it would be wise to reconsider the extent

of the fiscal adjustment to be sustained by those countries. Furthermore,

the lack of political resolve to implement structural reforms, which

had already lost momentum since the mid-2000s, is evident. Moreover,

since the early 2000s a number of countries in the transition region

have seen a levelling off of democratic progress.

76. Recent developments in some countries in the SEMED region,

however, have been encouraging. In Morocco and Jordan the role of

elected parliaments has been further strengthened. After a period

of uncertainty, in Tunisia the new constitution was finally approved

in 2014, which can be seen as a positive development in the country's

transition to democracy. Challenges in the political transition

in Egypt are still present, and the country maintains the status

of potential recipient. Nevertheless, despite the political uncertainty,

the Bank made considerable progress in the region. In November 2013,

Tunisia, Jordan and Morocco were each granted the status of recipient

country. The Bank also opened resident offices in Tunis, Cairo,

Casablanca and Amman, to cultivate relations with the respective

authorities and business communities. The EBRD invested €449 million

in 21 operations in the region in 2013 and expects its investment

volume to increase up to €2.5 billion by 2015. Social issues in

the new transition region relate to the high unemployment rate among

young people and low female participation in the labour force. With

this in mind, the expansion of the Bank's project selection criteria

to include social inclusion and equality of opportunity should be

welcomed.

77. The developments in Ukraine in the latter part of 2013 and

first part of 2014 offer an important window of opportunity to foster

transition. The EBRD is in a position to play an instrumental role

by providing leadership and external support. In this connection,

the stated intention of the Bank to support Ukraine by augmenting

its financial engagement in the country and increasing policy dialogue

with the authorities should be supported and further encouraged.

The new drive towards increased policy dialogue already resulted

in the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding with the government

for the Ukrainian Anti-Corruption Initiative.

78. The EBRD is well aware that the case for its operations has

considerably strengthened in the post-crisis world. During the 2014

Annual Meeting, the EBRD shareholders discussed the new medium-term

directions that will guide the Bank's activities over the following

years. These include a three-pronged approach to re-energise transition

in the EBRD region, a new focus on the Bank's geographic vision

and a modernisation of its planning process. The medium-term directions

provide a starting point for discussion of the Bank's Fifth Capital

Resources Review (CRR5), which will cover the period 2016 to 2020

and is to be approved at the Bank's 2015 Annual Meeting in Tbilisi.

79. In an attempt to better align the Bank's priorities and the

constraints posed by the environment in which it operates, the EBRD

aims to introduce a Strategic Implementation Plan (SIP). This is

to be welcomed as it would make the planning process more flexible

and less prescriptive by easing the burden of the Capital Resources

Review and the Annual Business Plan. Finally, the Bank's Fifth Capital

Resources Review is also expected to propose a reorganisation of

the composition of the Board of Directors, with the aim of increasing the

weight of the countries of operations. The strategic directions

also include a consensus view on the expectation of graduation from

the Bank's operations of the seven EBRD recipient countries that

joined the European Union in 2004. Furthermore, they maintain a

general orientation towards increasing operations in the east and

south of the region, also in accordance with recent geopolitical

developments.

80. The EBRD aims to re-energise transition by concentrating its

efforts around three key aims: i) supporting governments in hastening

transition through policy dialogue; ii) promoting economic integration

both globally and regionally; and iii) addressing globally common

challenges, such as climate change, energy and food security and

water scarcity. Increased emphasis on policy dialogue is to be supported,

as it is crucial to re-think institutional capacity. In this connection,

the signing of the Partnership for Re-energising the Reform Process in

Kazakhstan constitutes a significant achievement and its progress

should be carefully monitored. If successful, it may constitute

a blueprint to re-energise transition in other middle-income countries.

Concretely, the Bank could promote regional economic integration

by introducing new international investors to the region, and by

financing projects aimed at the development of cross-border infrastructures.

In this respect, the Bank is also devising a new Post-Graduation

Special Fund, to which countries can access after graduating in

order to finance cross-border infrastructure projects. The establishment

of such a fund should be welcomed, insofar as it has the potential

to deepen regional integration and increase the palatability of

graduation.

81. In the meantime, the Bank has already experienced relevant

changes concerning its internal structure, in the context of the

modernisation agenda initiated by President Chakrabarti. The initiative,

which was denominated One Bank,

focuses on the need to streamline the Bank's internal procedures

and modernise its management culture. This resulted in the creation

in 2012 of two new vice-presidencies, one for policy and one for

human resources and corporate services. The establishment of the

Vice-Presidency for Policy should be seen as an effort to strengthen

the link between the Bank's investments and the economic reforms

to be adopted at the broader sector and country levels. Meanwhile,

the Bank's expansion has continued. During its 2014 Annual Meeting,

EBRD shareholders granted the status of recipient country to Cyprus,

in order to help the country to rebalance its economy. Moreover,

Libya's request to become the 67th shareholder of the Bank was accepted.

Any further decision to grant recipient country status to Libya

would be taken separately, following a thorough assessment by the

Bank of the political, economic and operational environment in the country,

on the basis of Article 1 of the Agreement Establishing the Bank.