1. Introduction

“Unprecedented global forces

are shaping the health and well-being of the largest generation

of 10- to 24-year olds in human history. Population mobility, global

communications, economic development and the sustainability of ecosystems

are setting the future course for this generation and, in turn,

mankind. At the same time we have come to new understandings of

adolescence as a critical phase in life for achieving human potential.”

The Lancet Commission on Adolescent

Health and Wellbeing”

1. Adolescents can be challenging.

They are sometimes demonised and medicalised in relation to “problems”.

Adolescents can also be enthusiastic, energetic and passionate about

issues relevant to their own concerns such as education and health

and to the future of the world such as poverty, climate change and migration.

Adolescents are generally healthy, but there are sufficient numbers

who have problems to merit an increased focus on research and interventions.

Adolescence is a time in which positive changes can be made and

difficulties addressed and resolved. We must take better account

of the potential of adolescence for achieving human potential, for

the benefit of the whole society.

2. The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)

notes that achieving the right to health is dependent on the realisation

of many other rights, such as those inherent in social determinants

– the conditions in which people are born and live.

The

World Health Organization (WHO) produced as long ago as 1993 a report

on the health of adolescents

and has continued to publish statements

and guidance. The United Nations Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF)

has published a draft “Young People’s Agenda” for consultation.

It calls for a response to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

by involving leaders from governments, private sector, civil society

and youth organisations in delivering change in protecting and empowering

adolescents through education, health, skills and training.

3. This report takes up some of the global implications raised

by the Lancet Commission

and by international

organisations. Five key principles underpin its content: 1) adolescence

is a key stage of life and merits attention and investment; 2) young

people should participate in developing strategies which affect

their health; 3) welfare and other services should be co-ordinated

in a holistic way; 4) inequalities seriously undermine health and

must be addressed in order to prevent poor outcomes; 5) international

strategies for action need to be implemented at national, regional

and local levels and success or failure evaluated. These principles

will be reinforced in the sections related to mental health, sexual

health and obesity. The report seeks to present a brief overview,

a “snapshot” of factors influencing the health of adolescents and

what may be done in order to improve their lives and involve them

in doing so. It is based on selected research and the experiences

of young people, researchers and practitioners, and draws conclusions

on how the nations of Europe might develop and implement health

strategies which serve all adolescents, irrespective of their backgrounds.

A study visit to Sweden provided examples of challenges and good

practice (for further information, see document

AS/Soc/Inf

(2019) 01 on the website of the Committee on Social Affairs, Health

and Sustainable Development).

2. Adolescence is a key stage of life

which merits attention and investment

2.1. Defining

adolescence

4. For the purposes of this report,

the WHO definition is adopted: an adolescent is a person between

the ages of 10 and 19; young people are individuals between the

ages of 10 and 24. A child is someone between the ages of 0 and

18.

5. Adolescence is a unique phase of life in that it is one of

biological development, social experiences and identity building.

In particular, the impact of hormonal changes and an increased emphasis

on relationships and sexuality can make life complex for adolescents.

Added to this, the digital age and social media, whilst offering

opportunities for learning and interaction, also pose problems of

the potential exploitation of young people, including sexual exploitation.

Facebook and Google have been urged to take more responsibility

for the pressures they place on young people.

2.2. The

life course approach

6. Delivering health services

for adolescents is more than focusing on individual aspects of health,

such as smoking, drug use, diet, mental health and sexual health

at a specific age. Young children become adolescents, who in turn

become adults and grow old. Over this period, health needs will

change and a life course approach to health is required. Such an

approach aims to introduce or reinforce interventions throughout

life. It includes a healthy start to life and addresses the needs

of people, with their participation, at all stages. It addresses

the causes of ill health and promotes timely investment and a good

return for money spent. For example, education about relationships

and sexuality is delivered from different sources, before the onset

of sexual relations. In schools a “spiral” curriculum can be developed

which introduces and repeats concepts such as friendship as the

child matures. This can lead on to discussions about contraception,

sexually transmitted infections and sexual relationships at later

stages.

7. Recent research indicates that the influence of brain development,

within physical and hormonal changes and social and environmental

influences, contributes greatly to adolescent health outcomes. The Welcome

Trust has an extensive programme of research on the teenage brain

entitled “Neuroscience and Education”.

In 2017, the UNICEF office of research

(Innocenti) produced a compendium of articles under the title: “Adolescent

Brain Development: a Second Window of Opportunity”. They include:

the developing brain in its cultural contexts; poverty and the adolescent

brain; helping teenagers develop resilience; mindfulness mediation

and its impact; and the perils and the promise of technology for

the adolescent brain.

2.3. Characteristics

of adolescent health

8. According to the United Nations

World Population Prospects revision of 2015, the proportion of the adolescent

population in countries of Europe is 14%.

The number

of adolescents has grown as a result of prevention and intervention

focused on childhood health problems such as malnutrition, infant

mortality and infectious diseases. Whilst in some countries these

concerns still exist, what we are now seeing is a rise in concerns

about mental health, obesity and sexual health.

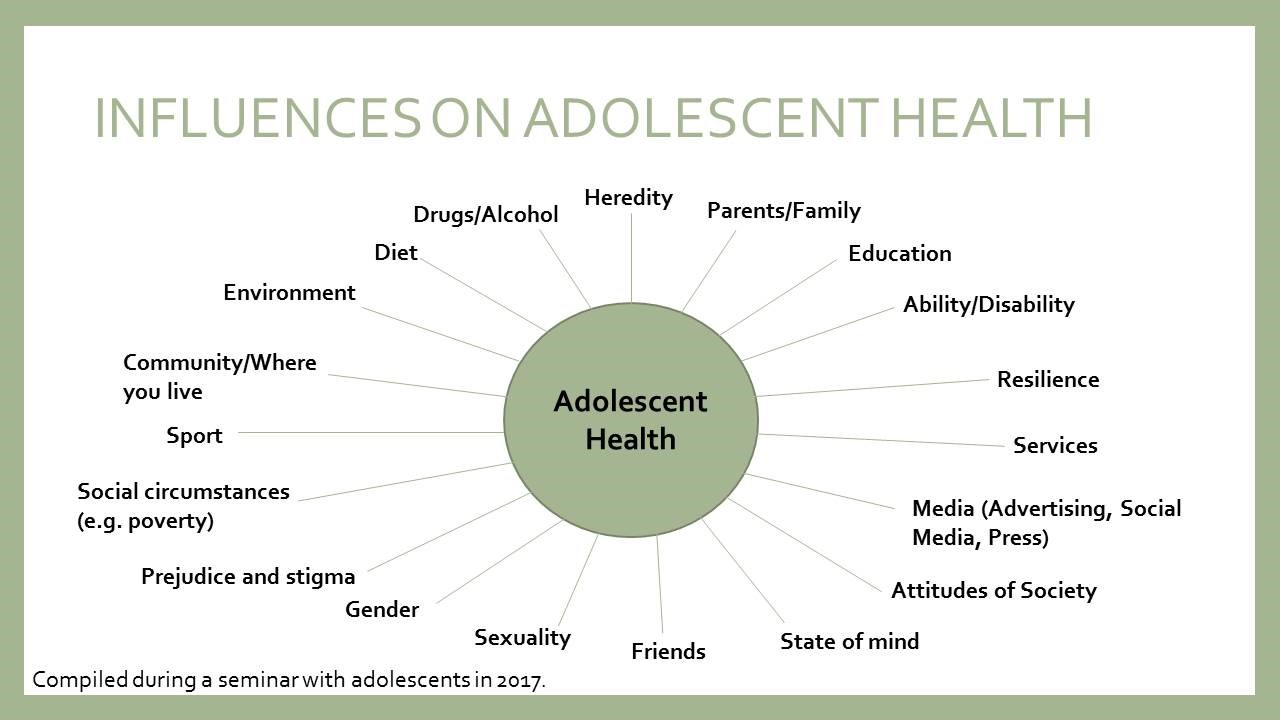

9. Adolescents are not a homogeneous group and the concept of

health cannot be separated from the context in which it exists.

Health has social determinants which influence health and well-being

status (see Diagram 1 below). Health inequalities still exist and

will profoundly affect the life chances of adolescents. WHO considers

that gender and socioeconomic differences in young people’s health

and well-being are of fundamental importance

. Some young people have greater health

risks than others, particularly those living in deprivation, those

with disabilities, those from ethnic minorities, lesbian, gay, bisexual,

transgender or intersex (LGBTI) young people and those in the youth

justice system. Young people living in zones of armed conflict are

vulnerable to exploitation and trauma.

Lack

of stability due to displacement and migration, poor education,

abuse and lack of support have powerful negative impacts and need

to be addressed in urgent ways.

Diagram 1: Influences on adolescent

health

10. Increased emphasis on education,

especially for girls, provides greater opportunity, potential and encourages

ambition. Laws such as those on forced marriage and female genital

mutilation, whilst not always adhered to, exist to protect young

people. Other laws may restrict their rights; sexual rights, for

example, are, in some countries still limited and deny the education

and services essential to the welfare of adolescents. Whilst most

countries have ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights

of the Child, cultural practice and national laws may lead to young

people’s rights being infringed.

2.4. Health

services for adolescents

11. Two opinions from young people

reflect the importance of having readily accessible services specifically designed

for young people. A 20-year-old woman said: “I believe promoting

more youth friendly health services is the most significant point,

as I feel there is great importance in making health care accessible

for young people.” Another stated: “Very often there is no help

available until the problem has become totally unmanageable.”

Many adolescents

are not getting the help they want when they want it. The situation

is further complicated by adolescents being on the cusp between

childhood and adulthood. They are all too frequently pushed into

services designed for adults and run by professionals without specific

training to deal with the needs of a younger age group. There is

an urgent need to improve levels of trained staff and to co-ordinate

between the different services. As one young person from an advocacy

group stated: “Young people do not want to be sent to a different

service for every different problem they are dealing with. They

want someone to help them through a variety of different issues,

recognising that they are often connected.”

12. Education for health is also important, particularly when

linked to other services. Health Promoting Schools

and

Rights Respecting Schools

exist

in small numbers across Europe. In these schools, young people learn

about their rights and health options. In addition, they may be

put into contact with professional services outside school. Health

Education, however, is rarely given mandatory status in the curriculum.

Where it exists, it is often purely biological and consists of one-off

lessons. Some schools do have programmes which not only include

information, but also encourage pupils to explore their attitudes

and values and foster decision- making skills. That said, the numbers

of school nurses and counsellors are often inadequate to cope with

young people’s health problems.

In England, after

many years of lobbying of government by politicians, professionals,

parents, young people and non-governmental organisations (NGOs),

Personal, Social and Health Education (PSHE) has been made mandatory

and includes wider aspects such as relationships and interaction

with environmental factors.

Higher

education institutions need greater support to develop health and

pastoral care systems.

2.5. Why

invest in adolescent health?

13. The 2016 Lancet Commission

considers that adolescent health has been grossly neglected.

The 2014 WHO report on adolescent

health states that adolescence is a critical time for human development

and should be given particular attention.

A 2018 World Bank report estimates

that over 90% of research publications focus on children under five.

Unarguably, the early years of human

life are important. Children deserve attention, and good access

to services,

but

so do adolescents. Attention paid solely to the under-fives may result

in national deficits of data, research, funding, policy and action

for adolescents. Focus on the early years has undoubtedly helped

with achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), but development

which occurs just before adulthood is equally important due to its

complex nature and amenability to intervention.

14. Adolescence is a dynamic and formative stage in the passage

to adulthood which can greatly contribute to satisfaction and achievement,

but can also give rise to negative experiences and difficulties.

UNICEF stresses the need to invest

in adolescence, not only because it is “right in principle” but

also because it safeguards the initial investment in health and

provides an early start for societal goals such as alleviating poverty,

achieving equity and eliminating discrimination.

Investment in health also helps to

equip adolescents with the necessary tools and coping skills for

present and future challenges.

The Lancet

Commission states that investment in adolescent well-being brings

a triple dividend of benefits now, in future adult life, and for

the next generation of children. Tackling preventable and treatable

adolescent health problems will bring huge social and economic benefits.

This is key to addressing health issues in all countries by 2030.

See the Appendix for further

information.

3. Mental

health

15. Research shows that most mental

health problems begin before the age of 25 and are most common between

the ages of 11 and 18.

Mental

health disorders can affect general health. For example, depression may

result in overeating and physical inactivity, with adverse consequences.

Not all problems persist into adulthood, especially if the episodes

are brief and appropriate interventions are applied, which are community based

with integration of services across health, education and social

sectors.

Public health expenditure

is relatively cost effective compared with health care expenditure.

Public Health England has estimated that the median return on investment

is 14.3 to 1.1.

16. WHO defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which

every individual realises his or her potential, can cope with the

normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully and

is able to make a contribution to her or his community”.

Mental

health problems may be more or less common, may be acute or long

lasting and may vary in severity. They manifest themselves in different

ways at different ages – for example, in children they may manifest

themselves as behavioural problems.

3.1. Influences

on mental health

17. In Diagram 1 above, influences

on adolescent health are suggested, recognising that such determinants may

have their origins in childhood and may persist into adulthood (the

Life Course). Determinants of mental health may include: truancy

rates at school and lack of education, attainment in the early years,

first contacts with the justice system, being in care, domestic

abuse, suicide of family or friends and stigma (including racial, religious

and sexual orientation prejudice). In addition, students in schools

and higher education report stress and depression due to tests and

examinations. The influence of the media can be positive (for example,

in the promotion of access to services and advice), but also can

be detrimental, for example in cyberbullying, the portrayal of violence,

as well as pornography and grooming. In the United Kingdom, out

of 1 000 young people aged between 11 and 25, 47% had experienced

bullying.

18. Over one third of 15 year olds in the United Kingdom are “extreme

internet users” – that is, they spend more than six hours of a weekend

day on the internet and 94% use the internet before and after school.

This year WHO has added “gaming disorder”

to its International Classification of Diseases.

Spending too much time online can

create social isolation. It can also create sleep deprivation and

poor quality sleep, which can cause problems with concentration

and with behaviour and self-image – 38% of young people report that

social media had a negative impact on how they feel about themselves;

48% of girls stated that social media had a negative impact on their

self-esteem.

3.2. Addressing

issues related to mental health

19. A Council of Europe/United

Kingdom Parliament seminar held in 2017 highlighted the links between mental

health and justice. The seminar brought together young people, parliamentarians,

NGOs, academics, lawyers and police officers. The recommendations

included the following: improving public awareness; reducing stigma

through campaigns; increasing funding for professional and non-professional

help for young people; improving access to school nurses and psychologists;

developing interdisciplinary services; ensuring that teachers are

trained to recognise signs of mental strain; and ensuring that young

people are listened to and their concerns taken into account, including

when developing laws and policies. At the Council of Europe level,

the Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading

Treatment or Punishment (CPT) should be encouraged to take more

interest in centres for mental health for children. Concerns were

expressed in relation to the number of young people with mental

health problems who enter the justice system, the effect of the

justice system on health and the disproportionate number of young

black men in the justice system. Positive examples included: Austria

(a high level of training for the judiciary), France (a family court

system based on multi-agency co-operation), Iceland (a Children’s

House model – a “one-stop shop” support system), and Nordic States

(increasing use of child-friendly interview techniques, including

video links and written statements). A young participant stated:

“Young people are experts by experience and their stories should

be heard.”

Another seminar for young people

held recently in London has expressed the need for the youth justice

system to be rehabilitative rather than punitive, with a particular

emphasis on mental well-being.

The Spanish interdisciplinary

network for the promotion of mental health and emotional well-being

in the young (PROEM) gives a comprehensive argument for the prioritisation

of mental health and effective interventions).

20. In the United Kingdom, the number of children referred for

mental health treatment by schools has soared by more than a third

in the last three years.

However,

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAHMS) have to turn

away 23% of children and adolescents. Evidence of the increase in

mental health problems, sometimes referred to as “a crisis”, has

resulted in a number of initiatives. There is a national strategy “No

Health without Mental Health”.

A green

(consultation) paper “Transforming children and young people’s mental

health” was issued in 2017.

The

government has committed an additional £1.4 billion to transform children

and young people’s mental health services. See the Appendix for

information on cost-effectiveness.

4. Sexual

health

21. Encouraging adolescents to

enjoy respectful and satisfying relationships and to protect themselves

not only from unplanned pregnancy, but also from sexually transmitted

infections, requires a combination of accurate information and advice,

services which are welcoming and friendly, and the participation

of young people in identifying their needs and giving advice on

what they find most useful.

22. According to WHO, in 2018, “[s]exual health is a state of

physical, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality.

It requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and

sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable

and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and

violence”.

The terms “sexuality” and “sexuality

education” are adopted in this report rather than the frequently misconstrued

“sex” and “sex education” which have biological connotations and,

to some, implies “having sex”. Educators working with young people

have often found this perception problematic.

4.1. Data

on adolescent sexual activity

23. Data may be questionable, due

to lack of accurate records and incorrect statements by adolescents,

but in Europe, there is reasonably comprehensive data on the sexual

activity of adolescents. For example, there are four teenage births

to women per 1 000 between the ages of 15 and 19 in the Netherlands,

14 in the United Kingdom, 38 in Georgia and 37 in Albania. Sexually

transmitted infections are rising amongst adolescents in European

countries and the increase is higher than in any other group. Condom

use is more frequent than the pill, but the lack of condom use amongst

adolescents leaves them vulnerable to STIs, the rates of which are climbing;

the highest numbers of infections are found among adolescents from

lower and middle income groups.

Whilst advances have

been made globally in the prevention of new HIV infection, progress

has been slow. Globally, HIV/AIDS was the ninth leading cause of

death amongst young people between the ages of 10 and 19 in 2015.

Only 36% of young men and

30% of young women aged 15 to 24 had a good knowledge of how to

prevent HIV according to available data for 2011-2016 in 37 countries.

Adolescents

in Europe are lacking accurate information, and the skills to negotiate

safer sex. They frequently describe their knowledge about sexuality

as “Too little, too late”.

4.2. Addressing

issues related to adolescent sexual health

24. The reasons for early sexual

activity and lack of protection are varied: socio-economic status,

lack of family openness in discussing sexuality and the use of alcohol

or other substances which lower the locus of control.

It is clear that improvements in

awareness and practice can change sexual habits. The UK Teenage Pregnancy

Strategy combines efforts from communities, young people, schools

and services with focus on reducing the high rates of teenage pregnancies.

Between 1992 and 2014, conception

rates fell by 51% with considerable reductions in geographical areas

of high conceptions.

25. Young people should have the right to advice at the start

of their sexual and reproductive lives. However, parents may be

reluctant to engage in such discussions, adolescents may not wish

to discuss sexuality with their parents, and information from friends

or the media might be misleading. Specialist health or education services

are therefore important in providing advice and information.

26. A consensus statement from Public Health England supports

a positive, life course approach involving choices and control as

opposed to the absence of disease or poor outcomes; services that

are inclusive of the population’s needs and responsive to diverse

characteristics; an agreed ethical framework, which takes account

of stigma and shame at all stages of life at an institutional and

individual level; and campaigns that challenge stereotypes and taboo.

27. Young people have made it clear what kind of services they

find most helpful: non-judgmental, confidential, free, and staffed

by sympathetic and knowledgeable staff. One example of such services

is provided by Brook Advisory Centres for young people in nine regions

of the United Kingdom, established over 50 years ago, amidst great

controversy, by the pioneer Helen Brook. These Centres provide comprehensive services

in sexual health for young people up to the age of 24.

4.3. Comprehensive

sexuality education

28. Comprehensive sexuality education

follows the concept of the life course approach to adolescent health. It

advocates structured programmes, which begin with simple information

and discussion about friendship and body parts and move on to more

complex aspects of relationships and sexual behaviour as the child

matures into adolescence and beyond.

29. An overview of sexuality education in the 25 countries of

the WHO European Region concluded that “remarkable progress” in

developing sexuality education has been made since the year 2000.

Other evidence supports

this, but quality and comprehensiveness may not be universal in

the region. Many service providers and educators have struggled

to establish even minimal rights for young people to be provided

with information.

30. UNESCO puts forward the following framework for consideration:

comprehensive sexuality education should cover the full range of

topics (even if they are challenging in some social and cultural

contexts); it should be based on a human rights approach, which

includes gender equality, and should encourage young people to recognise

their own rights, respect the rights of others and advocate for

those whose rights are violated. It may have reference to the overall

well-being of young people whilst impacting the prevention of HIV,

STIs, unintended pregnancy and gender-based violence. It should

provide opportunities to nurture positive values and attitudes toward

sex and relationships and develop life skills to support healthy

choices.

Comprehensive sexuality

education may be included in health education which encompasses

not only the formal school curriculum, but also school ethos and

policies, liaison with parents and communities, and linking with

youth organisations. See the Appendix for information on cost-effectiveness.

5. Obesity

31. Obesity in children and young

people is a relatively new phenomenon, but the problem is global

and has spread at a disturbing rate. It has been called one of the

most serious public health challenges of the 21st century

and

is increasingly affecting low and middle income countries, particularly

in urban settings.

32. The body mass index (BMI) is a person’s weight in kilograms

divided by their height in metres squared. Obesity is defined as

a BMI of 30 and above. Overweight is a BMI of 25 to 29.9.

BMI is measured differently in adults

and children and is evaluated using age and gender specific charts

that take into account the different growth patterns. Weight and

the amount of fat in the body differs for boys and girls and those

levels change as they grow; it is expressed as percentiles. BMI

levels in children and adolescents are expressed relative to other children

of the same age and gender. In adolescence a percentile higher than

95 is considered obese and an 85 to 95 percentile as overweight.

5.1. Data

on obesity

33. Globally, in 2016, the number

of overweight children under five was estimated at over 41 million.

In the WHO Europe region, in 2008, one in three 11-year olds were

overweight; over 50% of both men and women were overweight and 23%

of women and 20% of men were obese. Currently 30% to 70% of men

and women are overweight and 10% to 30% are obese.

Whilst

the European region has achieved great success in improving adolescent

health in recent years, obesity continues to rise in all but a few

countries, with marked disparities. In 10 of the 16 countries and

regions, patterns of social inequality were observed. However, none showed

a significantly higher prevalence of obesity amongst the most affluent

adolescents.

5.2. Influences

on obesity

34. Adolescents become overweight

or obese for a number of reasons, most commonly due to genetic factors,

lack of physical activity, unhealthy eating patterns or a combination

of these factors. In some rare cases, obesity is caused by a medical

condition such as a hormone problem. TV viewing is decreasing across Europe,

but computer usage increased significantly between 2002 and 2014.

Increases in computer use are more evident in girls. The current

guidelines of less than two hours a day of computer or TV usage

is not met by the majority of European adolescents.

Poor

nutrition is the largest factor contributing to poor health, with one

particular cause being the drinking of sugar-laden fizzy soft drinks,

drinks from concentrates, milk drinks, sports and energy drinks

and flavoured waters. Their promotion often targets children and

adolescents. Obesity is more common in lower socioeconomic groups.

Such inequalities are either unchanged or have become greater since

2012. An estimated 27% of all adolescent obesity in Europe in 2014

was attributed to socio-economic differences.

5.3. Consequences

of obesity

35. Most health problems related

to obesity do not become apparent until adulthood. Childhood obesity

is strongly associated with risk factors for cardiovascular disease,

type 2 diabetes, orthopaedic problems and musculoskeletal problems

such as osteoporosis.

If

this trend continues then there will be 88 million people living

with diabetes in 2045 in comparison with 58 million today and the

total health-care costs of diabetes will rise to 175 billion euros

in 2045, not taking into account other indirect costs.

Obesity

could be linked to 12 types of cancer and will overtake smoking

as a leading cause of death within a couple of decades in countries

such as the United Kingdom.

Obese

children are at greater risk of school absence, psychological problems

and social isolation deriving in part from lower self-esteem.

5.4. Addressing

obesity in adolescence

36. Targeted efforts are needed

to break the cycle of obesity. Services should be aimed at adolescents,

to help them make positive changes in health behaviour. Policies

should promote awareness of, and access to, healthy diets and physical

activity,

through

co-ordinated actions of different government departments, communities,

the media and the private sector.

Parental

influence is significant, and needs to be supported. An overall

healthy lifestyle in mothers has an impact on the risk of obesity

in children.

37. Policy actions such as a tax on sugar sweetened drinks, school

food policies, marketing restrictions, food labelling and targets

for the food industry are needed to reduce levels of obesity. Taxes

on sugar, tobacco and alcohol have been suggested as a means of

achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and as part of

a broader public health approach in addressing the commercial determinants

of health.

In

the United Kingdom a regulatory approach was introduced in April

2018: companies manufacturing soft drinks with added sugar have

to pay a levy and there is a higher rate for drinks with higher

levels of sugar. This levy appears to be having a positive effect

as companies are substantially reducing the sugar content in drinks.

The voluntary reduction of sugar in foods was disappointing, with

only a 2% reduction in sugar in the first year. Companies tend to

work around public health concerns to preserve profit margins. Other

areas where legislation could have a positive effect are in agricultural

policy, food marketing and pricing, non-broadcast advertising and sponsorship.

38. The United Kingdom Parliamentary Health Committee recommended

restrictions on advertising and food promotion and giving greater

powers to local authorities to control fast food outlets and billboard advertising.

In 2016, the United

Kingdom set out a plan to combat childhood obesity and built on

this plan in 2018. A summary of actions includes sugar-intake reduction,

calorie reduction, consulting on advertising by introducing before

the end of 2018 a 9 p.m. watershed on television advertising of

high fat and sugar foods. Local trailblazer programmes will be introduced

with local partners to show what works in different localities. See

the Appendix for information on cost-effectiveness.

6. Conclusions

39. Mental health problems among

adolescents are of growing concern across Europe, challenges to

the well-being of adolescents in relation to sexuality are numerous

and obesity rates are growing at a disturbing rate. Meanwhile, it

is in adolescence that behaviours can be changed and foundations

for healthy and fulfilling lives can be laid. Addressing the health

needs of adolescents is imperative, not only for the present generation, but

for the future well-being of populations.

40. Addressing health issues of adolescents has substantial economic

benefits for their societies, including a significant economic impact

on the health system and the wider economy, with implications for

the Europe 2020 Strategy for Growth.

41. Although the amount of research into the consequences of adolescent

behaviours and attitudes is increasing, it is still behind the amount

of research into other age groups. This must be remedied at national and

international levels. It is not clear how many nations in Europe

have a national policy focusing on the needs and potential of adolescents

and the social and economic benefits of directing attention to this

age group.

42. As with other health-related interventions, it is difficult

to isolate the impact of a particular intervention on any health

issue from the determinants of health. It is clear, however, that

tackling these determinants will be key to overcoming poor health.

For example socio-economic status, in particular poverty, inequality

and deprivation, play a dominant role. Economies, which are based

on profit and have few incentives to pay attention to public health

concerns, have a major impact. Media promoting physical perfection

at any cost can be a major influence. Exclusive focus on individual

responsibility is therefore not sufficient, and systemic approaches

need to be developed. States need to formulate approaches to adolescent

health which are human rights based, non-patronising, inclusive,

and collaborative and which counteract stigma or discrimination.

43. Statements and declarations from international bodies are

useful and supportive. Improving adolescent health in the Council

of Europe member States is an important contribution to the United

Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

44. At country level, local initiatives based on needs assessment

and involving local communities are essential in order to deliver

and evaluate the impact of any initiative, and to share best practice.

Health interventions have proved to be most successful and efficient

when they meet the needs of adolescents. Adolescents are the best

experts on their health problems and concerns, and their views must

be taken into account when developing relevant policies and practices.

![]()

![]()

![]() One in five girls in the United Kingdom

self-harm because of worries about their appearance or what other

children have said about their sexual behaviour.

One in five girls in the United Kingdom

self-harm because of worries about their appearance or what other

children have said about their sexual behaviour. ![]()

![]() . Children with better emotional

well-being make more progress in primary schools and are more engaged

in secondary school. This alone suggests a good return for efforts

undertaken in academic settings.

. Children with better emotional

well-being make more progress in primary schools and are more engaged

in secondary school. This alone suggests a good return for efforts

undertaken in academic settings.![]() interventions

for child mental health are listed and analysed and have quantified

costs and benefits. For example, as regards prevention of conduct disorder,

every pound spent would yield £7.83, early intervention in psychosis

would yield £10.27 and suicide prevention would yield £43.99. This

includes costs linked to health-care, police and other emergency

services, loss of productivity due to premature death, as well as

grief and shock experienced by relatives.

interventions

for child mental health are listed and analysed and have quantified

costs and benefits. For example, as regards prevention of conduct disorder,

every pound spent would yield £7.83, early intervention in psychosis

would yield £10.27 and suicide prevention would yield £43.99. This

includes costs linked to health-care, police and other emergency

services, loss of productivity due to premature death, as well as

grief and shock experienced by relatives.![]()

![]() There

is evidence to show cost effectiveness of positive interventions

regarding safeguarding, school readiness, being in education, employment

or training and mental health.

There

is evidence to show cost effectiveness of positive interventions

regarding safeguarding, school readiness, being in education, employment

or training and mental health. ![]()

![]()

![]() two issues

are emphasised: “Strong and mandated central policy, supporting

bold, holistic local action is needed to impact what is arguably the

greatest health challenge of the 21st century …” and “Learning from

joined-up programming emphasises the importance of not only improving

child nutrition, health education and physical activity, … but also

water consumption, access to affordable nutritious food, parent

education … and including improvements in the built environment.”

two issues

are emphasised: “Strong and mandated central policy, supporting

bold, holistic local action is needed to impact what is arguably the

greatest health challenge of the 21st century …” and “Learning from

joined-up programming emphasises the importance of not only improving

child nutrition, health education and physical activity, … but also

water consumption, access to affordable nutritious food, parent

education … and including improvements in the built environment.”![]() The

cost effectiveness of a four-year randomised controlled trial in

a school-based obesity programme in 18 elementary schools saved

US$317 per student balanced against the cost of the intervention.

The

cost effectiveness of a four-year randomised controlled trial in

a school-based obesity programme in 18 elementary schools saved

US$317 per student balanced against the cost of the intervention. ![]()

![]()