1. Introduction

1. The United Nations Human Rights

Council declared in its Resolution A/HRC/RES/32/13 of 1 July 2016 that

“[…] the same rights that people have offline must also be protected

online, in particular freedom of expression, which is applicable

regardless of frontiers and through any media of one’s choice, in

accordance with articles 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human

Rights and of the International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights.” In doing so, it recalled its Resolutions A/HRC/RES/20/8

of 5 July 2012 and A/HRC/RES/26/13 of 26 June 2014, on the subject

of the promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the

Internet.

2. The internet is a technological platform that can be utilised

for different purposes and for the provision of very different types

of services. Therefore, the internet cannot be seen as a medium

comparable to the press, radio and television, but rather as a distribution

platform which can facilitate the interaction between different

kinds of providers and users.

3. The internet is not only a space for what is generally understood

as public communication but also a platform that enables the operation

of different types of private communication tools (email and private messaging

applications in general) and has also created new hybrid modalities

which incorporate characteristics of both (for example, applications

that allow the creation of small groups or communities and the internal

dissemination of content).

4. Besides its communications features, the Internet has also

proved to be a very powerful tool to facilitate the deployment of

the so-called digital economy. The Covid-19 pandemic has particularly

intensified the electronic acquisition or provision of goods and

economic services thus creating new spaces for new business models

to prosper.

5. In the course of the recent years, a very specific category

of online actors has taken a central place in most legal and policy

debates.

6. In 2018, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe

adopted a Recommendation on the role and responsibilities of Internet

intermediaries,

which described these actors as

“(a) wide, diverse and rapidly evolving range of players”, which:

“facilitate

interactions on the internet between natural and legal persons by

offering and performing a variety of functions and services. Some

connect users to the internet, enable the processing of information

and data, or host web-based services, including for user-generated

content. Others aggregate information and enable searches; they

give access to, host and index content and services designed and/or

operated by third parties. Some facilitate the sale of goods and

services, including audio-visual services, and enable other commercial

transactions, including payments”.

7. The intermediaries have become main actors in the process

of dissemination and distribution of all types of content. The notion

of “intermediaries” refers to a wide range of online service providers

including online storage, distribution, and sharing; social networking,

collaborating and gaming; or searching and referencing.

8. This report will focus on what are generally known as hosting

service providers, and particularly those who tend to engage in

granular content moderation. This includes services provided by

social media platforms like Facebook or Twitter, content sharing

platforms such as YouTube or Vimeo, and search engines like Google or

Yahoo.

9. These providers play an important role as facilitators of

the exercise of the users’ right to freedom of expression. This

being said, it is also true that the role and presence of online

intermediaries raises two main areas for concern. Firstly, the important

presence of economies of scale, economies of scope as well as network

effects favours a high degree of concentration which may also lead

to significant market failures. Secondly, the biggest players in

these markets have clearly become powerful gatekeepers who control

access to major speech fora. Like in the case of – in many aspects,

still to be solved – concentrated actors exercising a bottleneck

power in the field of legacy media (particularly the broadcasting

sector), values such as human dignity, pluralism and freedom of

expression

also need to be particularly and

properly considered and incorporated into the legal and policy-making

debates around platform regulation.

10. The object of this report is to elaborate on these issues

in more detail, with a particular focus on how to preserve the mentioned

values in a context where no unnecessary and disproportionate constraints

are imposed, and different business models can thrive to the benefit

of users and the society as a whole.

11. My analysis builds on the background report by Mr Joan Barata,

who

I warmly thank for his outstanding work. I have also taken account

of the contributions by other experts,

and

by several members of the committee.

2. Hosting services as an economic activity

with gatekeeping powers

2.1. Platforms

and market power

12. Online platforms constitute

a particularly relevant new actor in the public sphere, first of

all in terms of market power. They operate on the basis of what

is called network effects. In other words, the greater the number

of users of a certain platform, the greater the benefits obtained

by all their users, and the more valuable the service becomes to

them. These network effects are cross sided as the benefits or services

received by a part of the users (individual users of social media,

for example) are subsidised by other participants (advertisers).

In view of this main characteristic, it is clear that the success

of these platforms depends on the acquisition of a certain critical

mass and, from there, on the accumulation of the largest possible

number of end users.

13. The British regulatory body OFCOM has remarked, in a recent

report on “Online market failures and harms”, that besides the mentioned

network effects, companies benefit from cost savings due to their

size (economies of scale) or their presence across a range of services

(economies of scope).

Of special economic importance is

also the use of data and algorithms: the collection of data regarding

users’ habits and characteristics may not only improve their experience

through personalised services but also facilitate a more targeted

advertising based on a profound knowledge of consumers’ preferences

and needs. This creates the necessity to collect the highest possible

amount of data from users, as well as disincentivises the users’

search for alternative services. On top on all these elements, it

is also important to underscore the fact that business models are

becoming more complex and sophisticated as big online platforms

often combine different offers of services: social media, search,

marketplaces, content sharing, etc. For this reason, the identification

of relevant markets for the purpose of competition assessments can

become particularly complex.

14. Still from a strictly economic point of view, network effects

and economies of scale create a strong tendency towards market concentration.

In this context of oligopolistic competition driven by technology, inefficiencies

and market failures may come from the use of market power to discourage

the entrance of new competitors and the creation of barriers to

switching services or from information asymmetries.

15. In the United States, in June 2019, the House Judiciary Committee

announced a bipartisan investigation into competition in digital

markets. The Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative

Law examined the dominance of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google,

and their business practices to determine how their power affects

the American economy and democracy. Additionally, the subcommittee

performed a review of existing antitrust laws, competition policies,

and current enforcement levels to assess whether they are adequate

to address market power and anticompetitive conduct in digital markets.

The subcommittee members identified a broad set of reforms for further

examination for purposes of preparing new legislative initiatives.

These reforms would include areas such as addressing anticompetitive

conduct in digital markets, strengthening merger and monopolization

enforcement, and improving the sound administration of the antitrust laws

through other reforms.

16. In the European Union, EU Commissioners Margrethe Vestager

and Thierry Breton presented in mid-December 2020 two large legislative

proposals: the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act.

The Digital Markets Act is aimed

at harmonising existing rules in member States in order to prevent

more effectively the formation of bottlenecks and the imposition

of entry barriers to the digital single market.

2.2. Platforms

and informational power

17. The power of online platforms

goes beyond a mere economic dimension. Even in the United States, where

decisions taken by platforms affecting – including restricting –

speech have been granted strong constitutional protection, the Supreme

Court has declared that social media platforms serve as “the modern public

square,” providing many people’s “principal sources for knowing

current events” and exploring “human thought and knowledge.”

18. Same legal and regulatory rules that apply to offline speech

must in principle also be applied and enforced regarding online

speech, including content distributed via online platforms. Enforcement

of general content legal restrictions

vis-à-vis online

platforms – and consequent liability – constitutes a specific area

of legal provisions that in Europe is mainly covered by the e-commerce

Directive (in the case of the European Union

)

and the standards established by the Council of Europe. The Annex

to the already mentioned Recommendation CM/Rec(2018)2 of the Committee

of Ministers to member States on the roles and responsibilities

of internet intermediaries indicates that any legislation “should

clearly define the powers granted to public authorities as they

relate to internet intermediaries, particularly when exercised by

law-enforcement authorities” and that any action by public authorities

addressed to internet intermediaries that could lead to a restriction

of the right to freedom of expression must respect the three-part

test deriving from Article 10 of the European Convention on Human

Rights (ETS No. 5).

19. Besides this, hosting providers do generally moderate content

according to their own – private – rules. Content moderation consists

of a series of governance mechanisms that structure participation

in a community to facilitate co-operation and prevent abuse. Platforms

tend to promote the healthiness of debates and interactions to facilitate

communication among users.

Platforms adopt these decisions

on the basis of a series of internal principles and standards. Examples

of these moderation systems are Facebook’s Community Standards,

Twitter’s Rules and Policies

or YouTube’s Community Guidelines.

In any case, it is clear that platforms

have the power to shape and regulate online speech beyond national

law provisions in a very powerful way. The unilateral suspension

of the United States former President Donald Trump accounts on several

major social media platforms has become a very clear sign of this

power. The amount of discretion that global reaching companies with

billions of users have in order to set and interpret private rules

governing legal speech is very high. These rules have both a local

and global impact on the way facts, ideas and opinions on matters

of relevant public interest are disseminated.

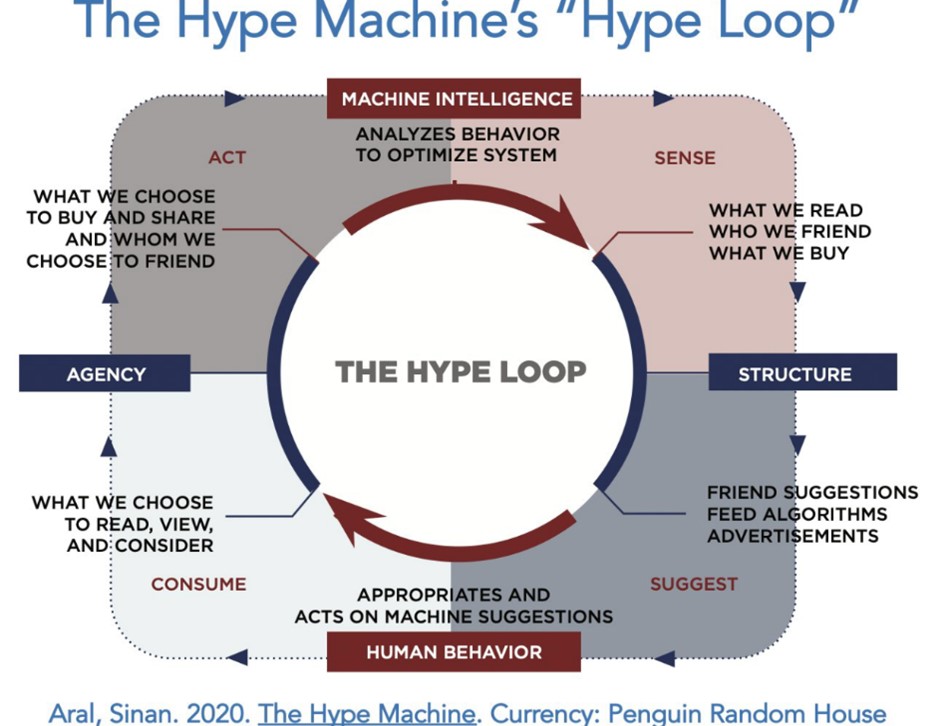

20. Many authors and organisations have warned that intermediaries

promote content in order to maximise user engagement and addiction,

behavioural targeting, and polarisation.

On the other hand, it is also important

to note that public understanding of platforms’ content removal

operations, even among specialised researchers, has long been limited,

and this information vacuum leaves policy makers poorly equipped

to respond to concerns about platforms, online speech, and democracy.

Recent improvements in company disclosures may have mitigated this

problem, yet a lot is still to be achieved.

This

being said, it is also worth noting that big platforms already have

a long record of mistaken or harmful moderation decisions in areas

such as terrorist or extremist content.

21. Platforms do not only set and enforce private rules regarding

the content published by their users. They also engage in thorough

policing activities within their own spaces as well as play a fundamental

role in determining what content is

visible online

and what content – although published – remains hidden or less notorious

than other. Despite the fact that users are free to directly choose

content delivered via online hosting providers (access to other

users’ profiles and pages, search tools, embedding, etc.) platforms’

own recommender systems are extremely influential inasmuch as they

are in a central position among their interfaces and have become

key content discovery features.

Being true that final recommendation

results are the outcome of a bilateral interaction between the users

– including their preferences, bias, background, etc. – and the

recommender systems themselves, it also needs to be underscored

that the latter play an important gatekeeping role in terms of prioritisation,

amplification or restriction of content.

22. On the basis of the previous

considerations it needs to be underscored, firstly, that no recommender system

is or can be considered or pre-determined to function on a completely

neutral basis. This is due not only to the influence played by users’

own preferences but also by the fact that platforms’ content policies

are often based on a complex mix of different principles: stimulating

user engagement, respecting certain public interest values – genuinely

embraced by platforms or as the result of policy makers and legislators’

pressures –, or adhering to a given notion of the right to freedom

of expression. Probably the only case where a set of content moderation

policies might deserve the qualification of neutral would be, in

fact, the absence of them. However, requesting platforms to host,

under no categorisation or pre-established criteria, a pile of pieces

of raw content, subjected to the only requirement of respecting

the law, would transform them into cesspools where spam, disinformation,

pornography, pro-anorexia and other pieces of harmful information

would be constantly presented to the user. This scenario is not

attractive either for users or for companies. Moreover, experiences

of this kind of initiatives – such as 4chan or 8chan in the United

States – have shown that among other options, platforms of this

nature are often used by groups promoting anti-democratic values,

questioning the legitimacy of election processes and disseminating

content contrary to the basic principles of human dignity – at least

the way this principle is understood and protected in Europe.

23. Secondly, no matter how precisely an automated, algorithmic

or even a machine learning tool is crafted, it can be arbitrarily

hard to predict what it can do. Unexpected outcomes are not uncommon,

and factors and glitches creating them can only be addressed once

detected. Some of these outcomes might certainly present important

human rights repercussions, particularly regarding the consolidation

of discriminatory situations: a scientific paper on technologies

for abusive language detection showed evidence of systematic racial

bias, in all datasets, against tweets written in African-American

English, thus creating a clear risk of disproportionate negative

treatment of African-American social media users’ speech.

24. The third remark refers to the idea of computational irreducibility

in connection with any set of ethical/legal rules. To put it short,

it cannot be reasonably expected that some finite set of computational

principles or rules that will constrain automated content selection

systems may always behave exactly according to and serving the purposes

of any reasonable system of legal and/or ethical principles and

rules. The computational norms will always be generating unexpected

new cases and therefore new principles to handle them will need to

be defined.

2.3. Disinformation

and elections as particular examples

25. This report cannot cover the

phenomenon of disinformation, mal-information and mis-information

in all its extension.

26. The notion of disinformation, which is the most commonly used,

covers speech that falls outside already illegal forms of speech

(defamation, hate speech, incitement to violence) but can nonetheless

be harmful.

According to the European Commission,

disinformation is verifiably false or misleading information that, cumulatively,

is created, presented and disseminated for economic gain or to intentionally

deceive the public and that may cause public harm.

It is in any case problematic as

it has direct implications on democracy, it weakens journalism and

some forms of traditional media, creates big filter bubbles and

eco chambers, it can be part of hybrid forms of international aggression,

through the use of State-controlled media, it creates its own financial

incentive, it triggers political tribalism, and it can be easily

automatised. Tackling disinformation, particularly when disseminated

via online platforms, requires undertaking a broad and comprehensive

analysis incorporating diverse and complementary perspectives, principles

and interests.

27. In addition to this, it is also important to note that the

problem is not really the disinformation phenomenon or fake news

itself, but the effect that the fake news creates – the manipulation

of people, often political, but not necessarily so.

Therefore, rather than putting the

focus on content regulation of disinformation, it is important to

concentrate the rules on the causes and consequences of it.

As the UN Special Rapporteur on

the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion

and expression, Irene Khan, has indicated in her first report to

the Human Rights Council on the threats posed by disinformation

to human rights, democratic institutions and development processes,

“disinformation tends to thrive

where human rights are constrained, where the public information

regime is not robust and where media quality, diversity and independence

is weak”.

28. Due to the direct connection with the right to freedom of

expression, an excessive focus on legal, and particularly, restrictive

measures could lead to undesired consequences in terms of free exchange

of ideas and individual freedom. According to the Joint Declaration

on freedom of expression, “fake news”, disinformation and propaganda

adopted on 3 March 2017 by the UN Special Rapporteur, the Organisation

for Security and Co-operation in Europe Representative on Freedom

of the Media, the Organisation of American States Special Rapporteur

on Freedom of Expression and the African Commission on Human and

Peoples' Rights Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and

Access to Information,

general prohibitions on the dissemination of

information based on vague and ambiguous ideas, including “false

news” or “non-objective information”, are incompatible with international

standards for restrictions on freedom of expression, State actors

should not make, sponsor, encourage or further disseminate statements

which they know or reasonably should know to be false (disinformation)

or which demonstrate a reckless disregard for verifiable information

(propaganda), State actors should, in accordance with their domestic

and international legal obligations, and their public duties, take

care to ensure that they disseminate reliable and trustworthy information,

including matters of public interest, such as the economy, public

health, security and the environment, and public authorities must promote

a free, independent and diverse communications environment, including

media diversity, ensure the presence of strong, independent and

adequately resourced public service media, and take measures to promote

media and digital literacy.

29. Connected to this, many experts and international organisations

have particularly warned about how the so-called information disorder

(in the terminology used by the Council of Europe

) distorted the communication ecosystem

to the point where voters may be seriously encumbered in their decisions

by misleading, manipulative and false information designed to influence

their votes.

Main

risk factors in this context are: the lack of transparency of new

forms of advertising online, which can too easily escape the restrictions

applicable to advertising on traditional media, such as those intended

to protect children, public morals or other social values; the fact

that journalists, whose behaviour is guided by sound editorial practices and

ethical obligations, are no longer the ones holding the gatekeeper

role; and the growing range of disinformation including electoral

information, available online, in particular when it is strategically disseminated

with the intent to influence election results.

3. Considerations

regarding possible solutions

30. I will present in the following

paragraphs the main principles, values and human rights standards

that I believe could be considered to articulate proper and adequate

solutions to the different issues mentioned above.

31. Regarding the economic power of platforms, it is important

to assess whether general competition law may be useful in order

to partially or totally address such matters, taking also into account,

as it has already been mentioned, the fact that the identification

of relevant markets for the purpose of competition assessments can

become particularly complex. The diversity and flexibility of business

models and services offered by a wide range of types of platforms

make it necessary a case-by-case analysis as well as the possible consideration

of specifically tailored ex post solutions, such as for example

data portability and platform interoperability. Interventions need

to be carefully considered and defined in order to avoid unintended

and harmful outcomes, particularly when it comes to incentives to

entry and innovation.

32. It is important to note that a few innovative remedies to

mitigate the power of platforms have already been presented by experts

in the field of what can be called “algorithmic choice”. These include

giving users the possibility of receiving services from third-party

ranking providers of their choice (and not those of the platform

they are using), which might use different methods, and emphasise

different kinds of content; or giving the user the choice to apply

third-party constraint providers, which would deliver content following

a classification previously made by the user him/herself.

In a recent contribution

by Francis Fukuyama and other authors, it is proposed that online

platforms are forced by regulation to allow users to install what

is generally called “middleware”. Middleware is software, provided

by a third party and integrated into the dominant platforms, that

would curate and order the content that users see. This may open

the door to a diverse group of competitive firms that would allow

users to tailor their online experiences. In the opinion of the

authors, this would alleviate platforms’ currently enormous editorial

control over content and labelling or censoring speech and enable

new providers to offer and innovate in services that are currently

dominated by the platforms (middleware markets).

This solution raises many interesting

questions, although its proper implementation would also need to

take into account important implications, particularly in terms

of data protection.

33. The law may regulate filtering (by any means, human or automated,

or both) by requiring platforms to filter out certain content, under

certain conditions, or by prohibiting certain content to be filtered

out. Such regulation would ultimately aim to influence users’ behaviour,

by imposing obligations on platforms.

This kind of legislation needs to

contain enough safeguards so that the intended effects do not unnecessarily

and disproportionately affect human rights, including freedom of

expression. In any case, any legislation imposing duties and restrictions

on platforms with further impact on user’s speech must be exclusively

aimed at dealing with illegal content thus avoiding broader notions

such as “harmful content”. In other words, it cannot enable or establish

State interventions which would otherwise be forbidden if applied

to other content distribution or publication means.

34. Regarding the use of artificial intelligence and automated

filters in general for content moderation, it is important to understand

that nowadays, and when it comes to the most important areas of

moderation, the state of the art is neither reliable nor effective.

Policy makers should also recognise the role of users and communities

in creating and enabling harmful content. Solutions to policy challenges

such as hate speech, terrorist propaganda, and disinformation will

necessarily be multifaceted and therefore mandating automated moderation

by law is a bad and incomplete solution.

It is also important to acknowledge

and properly articulate the role and necessary presence of human

decision makers,

as well as the participation of

users and communities in the establishment and assessment of content

moderation policies.

35. Regarding the specific case of election processes, the European

Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission) has recommended

a series of measures such as the revision of rules and regulations

on political advertising in terms of access to the media and in

terms of spending; enhancing accountability of internet intermediaries

as regards transparency and access to data, promoting quality journalism;

and empowering voters towards a critical evaluation of electoral

communication in order to prevent exposure to false, misleading

and harmful information, together with efforts on media literacy

through education and advocacy.

36. Apart from legal instruments, governmental and non-governmental

organisations at national, regional and international levels have

been developing ethics guidelines or other soft law instruments

on artificial intelligence, broadly understood. Despite the fact

that there is still no consensus around the rules and principles that

a system of artificial intelligence ethics may entail, most codes

are based on the principles of transparency, justice, non-maleficence,

responsibility, and privacy.

The

Consultative Committee of the Council of Europe Convention for the

protection of individuals with regards to the automatic processing

of personal data (ETS No. 108, “Convention 108”), adopted on 25

January 2019 the “Guidelines on Artificial Intelligence and Data Protection”.

They are based on the principles of the Convention and particularly

lawfulness, fairness, purpose specification, proportionality of

data processing, privacy-by-design and by default, responsibility

and demonstration of compliance (accountability), transparency,

data security and risk management.

37. On 8 April 2020 the Committee of Ministers of the Council

of Europe adopted the Recommendation CM/Rec(2020)1 to member States

on the human rights impacts of algorithmic systems. It affirms,

above all, that the rule of law standards that govern public and

private relations, such as legality, transparency, predictability, accountability

and oversight, must also be maintained in the context of algorithmic

systems. It also stresses the fact that when algorithmic systems

have the potential to create an adverse human rights impact, including effects

on democratic processes or the rule of law, these impacts engage

State obligations and private sector responsibilities with regard

to human rights. It therefore establishes a series of obligations

for States in the fields of legal and institutional frameworks,

data management, analysis and modelling, transparency, accountability

and effective remedies, precautionary measures (including human

rights impact assessments), as well as research, innovation and

public awareness. The recommendation also includes, beyond States’ responsibilities,

an enumeration of those corresponding to private sector actors, vis-à-vis the same areas previously

mentioned, and in particular the duty of exercising due diligence

in respect of human rights.

38. The European Commission, upon reiterate requests and demands

from other EU institutions, civil society and the industry, recently

proposed a new set of rules regarding the use of artificial intelligence.

In the opinion of the Commission, these rules will increase people’s

trust in artificial intelligence, companies will gain in legal certainty,

and member States will see no reason to take unilateral action that

could fragment the single market.

It is impossible to describe and

analyse the proposal within the framework of this report. In any

case it is worth noting that it essentially incorporates a risk-based

approach on the basis of a horizontal and allegedly future-proof

definition of artificial intelligence. Grounded in different levels

of risk (unacceptable risk, high-risk, limited risk and minimal

risk) the proposal articulates a series of graduated obligations,

taking particularly into account possible human rights impacts.

The Commission proposes that national competent market surveillance

authorities supervise the new rules, while the creation of a European

Artificial Intelligence Board would facilitate their implementation.

The proposal also envisages the possible use of voluntary codes

of conduct in some cases.

39. Entities that use automation in content moderation must be

obliged to provide greater transparency about their use of these

tools and the consequences they have for users’ rights.

Such rules must be capable of incentivising

their full and proper compliance.

It is also important that before

adopting any legal rule or regulation there is a proper and common

understanding about the kind of information that is necessary and useful

to be disclosed via transparency obligations and the public interests

that legitimise such obligations. In addition, civil society organisations

and regulators need to count on sufficient knowledge and expertise

in order to properly assess the information they may request within

the context of their functions and responsibilities. The proposed

Digital Services Act in the context of the European Union contains

remarkable provisions aimed at establishing transparency obligations

vis-à-vis online platforms graduated on the basis of size. They

include reporting on terms and conditions (article 12), content

moderation activities and users (articles 13 and 23), statements

of reasons regarding decisions to disable access or remove specific

content items (article 15), online advertising (article 24), and

recommender systems (article 29).

40. Transparency of social media recommendations has been classified

in three main categories: user-facing disclosures, which aim to

channel information towards individual users in order to empower

them in relation to the content recommender system; government oversight,

which appoints a public entity to monitor recommender systems for

compliance with publicly-regulated standards; and partnerships with

academia and civil society, which enable these stakeholders to research

and critique recommender systems. In addition to these areas, experts

have also advocated for a robust regime for general public access.

41. Additional areas vis-à-vis transparency

in the design and use of artificial intelligence include, firstly,

the relationship between the developer and the company: both parties

need to share information and a common understanding regarding the

system that is to be developed and the objectives it is going to

fulfil. Secondly, no matter how precise and targeted legal and regulatory

obligations may be, it might be important to count on proper independent

oversight mechanisms (also seeking to avoid lengthy litigation procedures

before the courts) that could check any specific transparency request

in order to properly safeguard certain areas of public or legitimate

private interests (for example, the protection of commercial secrets).

Thirdly, independent review mechanisms must count on proper outcome

assessment tools (both at quantitative and qualitative levels) in order

to scrutinise the adequateness and effectiveness of the rules in

place. Such tools need to particularly focus on identifying disfunctions

and unintended results (false positives) and impacts on human rights.

4. Conclusions

42. Online communication has become

an essential part of people’s daily lives. Therefore, it is worrying

that a handful of internet intermediaries are de

facto controlling online information flows. This concentration

in the hands of a few private corporations gives them huge economic

and technological power, as well as the possibility to influence

almost every aspect of people’s private and social lives.

43. To address the dominance of a few internet intermediaries

in the digital marketplace, member States should use anti-trust

legislation. This may

enable citizens to have greater choice when it comes to sites that protect

their privacy and dignity.

44. Crucial issues for internet intermediaries and for the public

are the quality and variety of information, and plurality of sources

available online. Internet intermediaries are increasingly using

algorithmic systems, which can be abused or used dishonestly to

shape information, knowledge, the formation of individual and collective opinions

and even emotions and actions. Coupled with economic and technological

power of big platforms, this risk becomes particularly serious.

45. The use of artificial intelligence and automated filters for

content moderation is neither reliable nor effective. Big platforms

already have a long record of mistaken or harmful content decisions

in areas such as terrorist or extremist content. Solutions to policy

challenges such as hate speech, terrorist propaganda and disinformation

are often multifactorial. It is important to acknowledge and properly

articulate the role and necessary presence of human decision makers,

as well as the participation of users in the establishment and assessment

of content moderation policies.

46. Today there is a trend towards the regulation of social media

platforms. Lawmakers should aim at reinforcing transparency and

focus on companies’ due processes and operations, rather than on

the content itself. Moreover, legislation should deal with illegal

content and avoid using broader notions such as harmful content.

47. If lawmakers choose to impose very heavy regulations on all

internet intermediaries, including new smaller companies, this might

consolidate the position of big actors which are already in the

market. In such a case, new actors would have little chance of entering

the market. Therefore, there is a need for a gradual approach, to

accommodate different types of regulations on different types of

platforms.

48. Member States must strike a balance between the freedom of

private economic undertakings, with the right to develop their own

commercial strategies, including the use of algorithmic systems,

and the right of the public to communicate freely online, with access

to a wide range of information sources.

49. Finally, internet intermediaries should assume specific responsibilities

regarding users’ protection against manipulation, disinformation,

harassment, hate speech and any expression which infringes privacy

and human dignity. The functioning of internet intermediaries and

technological developments behind their operation must be guided

by high ethical principles. It is from both a legal and ethical

perspective that internet intermediaries must assume their responsibility

to ensure a free and pluralistic flow of information online which is

respectful of human rights.

50. The draft resolution which I prepared builds on these considerations.